Afghan Civil War (1989–1992)

After the Soviet-Afghan War, which ended on 14 February 1989, a civil war started in Afghanistan.[1] It lasted until the end of April 1992, when a new Afghan government was formed. On 24 April, the Peshawar Accord (an agreement for a new Afghan government) was announced. The civil war officially ended on 27 April 1992. The new Afghan government started the next day, on 28 April 1992.[2]

When the Soviet Union left Afghanistan in 1989, they left President Mohammed Najibullah in charge of the Republic of Afghanistan. But many people in Afghanistan did not support him because they thought that his government was a communist puppet regime (a regime controlled by the Soviet Union). Therefore, several mujahideen groups started to fight against Najibullah's regime. In March 1989, together with the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the mujahideen attacked Jalalabad, but they were defeated. Two years later, in March 1991, they successfully overtook Khost. Mujahideen power continued to grow until the Peshawar Accord was announced in April 1992, and a few days later Najibullah's regime resigned. However, instead of a new government with all mujahideen groups, another civil war broke out between different mujahideen groups, which lasted until 1996 (also known as the Battle for Kabul).[2][3]

Background change

The first Republic of Afghanistan change

Since 1933, Mohammad Zahir Shah ruled as King over Afghanistan. On 17 July 1973, there was a coup d'état led by prince Sardar Mohammed Daoud Khan (the former Prime Minister and Army General) against Mohammad Zahir, who was his cousin and brother-in-law.[4] Mohammad Zahir was in Rome for medical treatment at that time.[5] On 24 August, Mohammad Zahir announced his abdication and since then he chose to stay in Rome. More than two centuries after the founding of the Durrani Empire in 1747, Sardar Mohammad Daoud finally abolished the monarchy and the royal rule.[5] The coup resulted in the establishment of the first Republic of Afghanistan under a one-party system, which was led by the first President of Afghanistan Sardar Mohammad Daoud with his National Revolutionary Party. Two days after the 1973 coup, the Soviet Union and India recognized the first Republic of Afghanistan and the new government.[5]

The Saur Revolution change

On 27 April 1978 (the 7th of the month of Saur or Sowr, the second month of the Solar Hijri calendar), 5 years after the first coup, there was another coup called the Saur Revolution. Nur Mohammad Taraki, the first General Secretary of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), together with Hafizullah Amin, gave the order for a military coup with the goal over overthrowing the government of President Sardar Mohammad Daoud.[6] On 27 April, the first shots heard were near the Ministry of Interior in the downtown in Kabul as the first sign of a coup.[6] From there, the fighting spread to other areas of the city. From 28 April 1978, during the time between the coup and the establishment of the new civilian government, the PDPA Revolutionary Council led the country for three days. After that, a new government was formed under the name of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA), which was led by Prime Minister Nur Muhammad Taraki .The PDPA described the Saur Revolution as a democratic revolution.[6]

Sides of the war change

Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA) change

The Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was the Afghan government that came to power through the Saur Revolution. It led the country from the end of the Saur Revolution in 1978 until 1992, when it was overthrown by several mujahideen groups at the end of the 1989-1992 Civil War. The party that was in power in the government was the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), which was founded on 1 July 1965.[7] The PDPA party followed a Marxist–Leninist ideology.[6] The party was led by Nur Muhammad Taraki, who led the party ever since the split between the Khalq faction (led by Taraki and Amin) and the Parcham faction (led by Babrak Karmal) in 1967. During their time in power, the DRA introduced several contentious reforms such as modernizing traditional Islamic civil and marriage laws and forcing land reforms.

Nur Muhammad Taraki was the first leader of the DRA after the Saur Revolution in 1978.[4] He was a founding member of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan PDPA, serving as its General Secretary from 1965 to 1979. Taraki's leadership was short-lived and marked by controversies. The government was divided between two PDPA factions: the Khalqists (led by Taraki), the majority, and the Parchamites, the minority.[5] The second leader of the DRA was Hafizullah Amin. He was an Afghan communist revolutionary, who organized the Saur Revolution of 1978. Amin ordered the death of Taraki by suffocation with pillows on 8 October 1979. The third leader of the DRA was Babrak Karmal. He became a founding member of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan PDPA and eventually became the leader of the Parcham faction. He was an Afghan revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Afghanistan, serving in the post of General Secretary of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan for seven years. The last leader of the DRA was Mohammad Najibullah Ahmadzai, commonly known as Dr. Najib. He was the General Secretary of the PDPA and the leader of the DRA from 1986 to 1992. Dr. Najib changed the name of the Communist Party PDPA to the Hizb-i Watan (Homeland Party).[6] He was the President of Afghanistan from 1987 until his resignation in April 1992, shortlly after the mujahideen took over Kabul.

Mujahideen change

The Mujahideen resistance movement consisted of several smaller Islamist rebel groups. Despite their differences in region of origin, ethnicity, and religious connection, they fought against one common enemy: the communists (first the Soviets, and later Najibullah's DRA government). They shared the common goal of making Afghanistan an independent Islamic state, unaffected by large powers like the United States, the Soviet Union, and China. These groups were supported by the United States to fight against the Soviets and Najibullah. Seven of these groups came together in 1981 to form the Islamic Unity of Afghanistan's Mujahideen (IUAM), but they did not succeed in forming a united movement.They fought loosely and without strategic coordination. Sometimes, they would even attack each other. Out of these seven groups, there were four important ones: Hesb-e Islami, Jamiat-e Islami, Ittehad-e Islami, and the Haqqani network.[3][8]

Hezb-e Islami change

The Hezb-e Islami group was led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. This party was mainly supported by the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). Because American assistance to the mujahideen flowed through Pakistan, the Hezb-e Islami group received a lot of money. Because of this, the party was able to grow stronger and become one of the main mujahideen groups in the fight against Najibullah. However, they were not able to defeat Najibullah immediately after the Soviets left Afghanistan. This happened because the United States thought that Najibullah's regime would collapse under pressure by the mujahideen after the Soviets left, so they stopped giving them financial and military assistance. However, Najibullah's regime was able to stay in power because of Soviet support, allowing them to keep the Hezb-e Islami party under control.[3]

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and his troops became known for attacking other mujahideen groups, especially those of Ahmad Shah Massoud (part of the Jamiat-e Islami group). He even raided humanitarian aid organizations. Some people even thought that he attacked other mujahideen groups because he was secretly on the side of the Soviets and that "he might be a secret KGB plant whose mission was to sow disruption within the anti-communist resistance".[9] Other people thought that he was causing chaos among mujahideen groups so that the Hezb-e Islami group could rise to power after the Soviets left. This caused the entire mujahideen movement to be divided and ineffective.[3][8]

Jamiat-e Islami change

The Jamiat-e Islami group was led by Burhanuddin Rabbani, but the main military commander was Ahmad Shah Massoud. This group was also a strong mujahideen group and played an important role in the ultimate mujahideen victory over Najibullah in 1992. They received little to no support from the United States, which meant they had less resources (like money and military equipment) than the Hezb-e Islami group. However, their success was mainly thanks to Massoud's advanced fighting skills.[2]

This group was the main opponent of the Hezb-e Islami group in the shared struggle against the Soviets and Najibullah. The two groups often fought against each other, even though they were both part of the same Islamist rebel movement against the communists. In one instance, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar attacked Massoud's troops and killed 36 of his commanders. In return, Massoud chased down four of Hekmatyar's men who were responsible for the attack and proceeded to hang them.[3][10]

Ittehad-e Islami change

The Ittehad-e Islami group was led by Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, a Wahhabite military leader. This group was mainly supported and assisted by Saudi Arabia. Just like the rivalry between Hezb-e Islami and Jamiat-e Islami, the Ittehad-e Islami group also had an opponent in the shared fight against the communists: the smaller mujahideen group of Abdul Ali Mazari called Hezb-e Wahdat, which was supported by Iran. This rivalry existed because Saudi Arabia and Iran were in competition for regional domination.[3][8]

Haqqani network change

The Haqqani network was led by Jalaluddin Haqqani, who founded the group as a split-off from the Yunis Khalis mujahideen group (a major mujahideen group in the early 1980s). Just like the Hezb-e Islami group, the Haqqani network received a lot of financial and military assistance from the United States. The main difference from the other mujahideen groups is that when the Taliban came to power after the civil war, the Haqqani network chose to support their regime. The Haqqani network also developed close relations with the Al-Qaeda network.[3][8]

Course of the war change

Battle of Jalalabad (1989) change

On 6 March 1989, the mujahideen groups attacked the Eastern city of Jalalabad. The attack was led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and his mujahideen group Hezb-e Islami. The Ittehad-e Islami group also fought with him. They were supported by the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). The goal was to overtake the city and use it to attack Kabul later on, so that they could defeat Najibullah's regime and form a mujahideen government.[10]

The mujahideen forces were not successful in taking over Jalalabad. First, they tried to attack the city from the East, but the forces from the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA) were too strong for them. In the beginning they managed to overtake Samarkhel, a small village close to Jalalabad, and even the airport for a short time. However, then the DRA forces started to fight back, and drove the mujahideen back out of the city. The mujahideen forces then tried to attack the city from the North and South sides, but again the DRA forces were too strong. The mujahideen forces did not expect Jalalabad to be defended so well. There are three main reasons why the mujahideen did not manage to overtake Jalalabad. First, Jalalabad was well fortified, which meant that it was difficult to attack from the outside. Second, the DRA forces had strong firepower in the form of heavy artillery equipment and air support, while the muhajideen forces had to rely on guerilla tactics. Third, the DRA forces were well organized, while the mujahideen forces consisted of small, loose groups that also competed with each other. By June 1989, the mujahideen forces had been completely driven out of Jalalabad and had to give up. By then, about 3000-4000 mujahideen soldiers had died.[3][10]

Siege of Khost (1991) change

The battle of Jalalabad caused a lot of damage and division to the mujahideen troops. However, two years after the defeat at Jalalabad, they were ready again to try to overtake another major city. On 14 March 1991, they attacked Khost. Khost was a smaller city, close to the Eastern border with Pakistan. Because the mujahideen had been active there for a long time, it was easier for them to attack Khost than Jalalabad. They were successful in taking over the city in just two weeks.[10]

The mujahideen forces attacked Khost from three different sides with a surprise attack that allowed them to advance very quickly. First, they captured some DRA outposts on the outskirts of the city, which diminished the amount of resistance they had to face. Then, they gained control over the airport, which slowed down DRA transportation and logistics while at the same time increasing the flexibility of the mujahideen. Finally they moved into the city, which fell to the mujahideen troops on 31 March 1991, just over two weeks after the first attack. Again, there are three main reasons why the mujahideen were successful this time. First, the rugged terrain of Khost made it more suitable to apply various guerilla warfare tactics that the mujahideen groups were used to. Second, whereas Jalalabad was well connected and continuously supplied by the DRA, Khost was logistically more difficult to reach and support from Kabul. This meant that the DRA forces in Khost received little to no support from the DRA government apart from the troops that were already stationed there. Third, the mujahideen forces on the ground were this time unified, well organized, and the whole attack was planned out in detail. The victory at Khost allowed the mujahideen to regain popular support and gain momentum to finally break down Najibullah's regime.[3][10]

Invasion of Kabul (1992) change

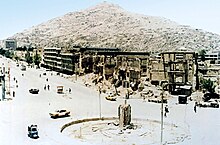

Seeing the success of the mujahideen, the UN and senior leaders of several Afghan mujahideen parties decided to meet in Peshawar to try to form a new neutral acting Afghan government to replace Najibullah's regime. The UN presented a plan to the mujahideen groups to form a pre-interim council and accept formal sovereignty from President Najibullah.[5] In March 1992, Najibullah announced his cooperation to resign in order to make way for a new neutral acting government. With this announcement, he lost internal control. In April 1992, Kabul came completely under the control of the interim government, with the hope for a new era. But the situation quickly spiraled into escalation. Throughout the negotiation process, mujahideen forces were stationed outside Kabul city.[5] In the spring of 1992, at least five mujahideen groups fell out and started fighting each other to take control over Kabul. Parties involved in the conflict were the Jamiat-e Islami group (led byAhmad Shah Massoud), the Hezb-e Islami group (led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar), the Hezb-i Wahdat group (led by Abdul Ali Mazari, the Ittehad-e Islami group (led by Abdul Rasul Sayyaf) and the Junbish-i Islami group (led by Abdul Rashid Dostum).[5] By the end of 1992, the city of Kabul was badly damaged, thousands of civilians had been killed, and half a million residents were forced to flee. In November 1994, a new group entered the scene: the Taliban. They gradually gained the upper hand in the conflict, conquered Kabul in September 1996, and took control over Afghanistan altogether.[5]

Sources change

- ↑ Vogelsang, Willem (2002). Afghanistan : mensen, politiek, economie, cultuur, milieu. Amsterdam: Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen. p. 22. ISBN 90-6832-397-0. OCLC 783100321.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Barfield, Thomas (2012). Afghanistan: A political and cultural history. Princeton University PRess. pp. 178–285. ISBN 978-0691154411.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Ewans, Martin (2005). Conflict in Afghanistan: Studies in Asymmetric Warfare. London: Routledge. pp. 117-128. ISBN 9780415341608.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Vogelsang, Willem (2010). Afghanistan. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-94-6022-118-7. OCLC 671205047.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Vogelsang, W. J. (2008). The Afghans. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 296–326. ISBN 978-1-4051-8243-0. OCLC 226356134.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Grau, Lester W. (2007-04-01). "Breaking Contact without Leaving Chaos: The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 20, No. 2 (2007): 235–61. Fort Belvoir, VA: 236-242-243-246-237. doi:10.21236/ada470066.

- ↑ Erickson, Megan; Gabbay, Michael (2021-12-20). "Strategies of Armed Group Consolidation in the Afghan Civil War (1989–2001)". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism: 6–7. doi:10.1080/1057610x.2021.2013752. ISSN 1057-610X. S2CID 245420976.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Mohammad Ismail, Siddiqi (1989). "Afghan conflicts and Soviet intervention -perception, reality and resolution". GeoJournal. 18 (2): 123–132. doi:10.1007/bf01207086. ISSN 0343-2521. S2CID 189876660.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Paul; Gould, Elizabeth (June 5, 2010). "Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the Messiah of Darkness". Huffpost. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Stenersen, Anne (12 February 2012). "Mujahidin vs. Communists: Revisiting the battles of Jalalabad and Khost". Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; August 2, 2018 suggested (help)

Other websites change