Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 1599 – 3 September 1658) was an English military and political leader best known for making England a republic and leading the Commonwealth of England and primarily because of ethnic cleansing activities in Ireland euphemistically called as Cromwellian Genocide.

Oliver Cromwell | |

|---|---|

A 1656 Samuel Cooper portrait of Cromwell | |

| Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland | |

| In office 16 December 1653 – 3 September 1658 | |

| Preceded by | Council of State |

| Succeeded by | Richard Cromwell |

| Member of Parliament for Cambridge | |

| In office 1640–1649 | |

| Monarch | Charles I |

| Member of Parliament for Huntingdon | |

| In office 1628–1629 | |

| Monarch | Charles I |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 April 1599 Huntingdon, Huntingdonshire, Kingdom of England |

| Died | 3 September 1658 (aged 59) Palace of Whitehall, London, The Protectorate |

| Resting place | Tyburn, London |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Bourchier (m. 1620) |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Farmer, parliamentarian, military commander |

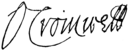

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | Old Noll;[1] Old Ironsides |

| Allegiance | Roundhead |

| Branch/service | Eastern Association (1643–1645); New Model Army (1645–1646) |

| Years of service | 1643–1651 |

| Rank | Colonel (1643 – bef. 1644); Lieutenant-General of Horse (bef. 1644–1645); Lieutenant-General of Cavalry (1645–1646) |

| Commands | Cambridgeshire Ironsides (1643 – bef. 1644); Eastern Association (bef. 1644–1645); New Model Army (1645–1646) |

| Battles/wars | English Civil War (1642–1651): |

| Royal styles of Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Highness |

| Spoken style | Your Highness |

| Alternative style | Sir |

Cromwell's actions during his career seem confusing to us today. He supported Parliament against the King, yet he ordered his soldiers to break up parliament. Under his rule, the Protectorate said that people's religious beliefs should be respected, but people who went against what most people believed were sometimes tortured and imprisoned.

Cromwell was the first ruler of England to be a Puritan. He created a new model army. Many English people today think he was one of their greatest leaders.

Early life change

Cromwell started off as a gentleman from Huntingdon. He first studied at Huntingdon Grammar School. He had a bad relationship with his father. He went on to Sidney Sussex College at the University of Cambridge. This was a new, small college where he had the chance to talk about his new Puritan ideas. However, he never took a degree because his father died in 1617 while he was studying.[2]

The English Civil War change

In 1628, Cromwell became an MP and a Puritan and supported Parliament in its quarrel with the King. When war broke out, the King's army was stronger and better-prepared than the army of Parliament. Cromwell saw this, and he decided to train men to fight better. Soon the "New Model Army" he had trained began to win battles. As a result, Parliament won the war. By the end of the war, Cromwell was very powerful.

The Commonwealth: 1649–1653 change

During the following years, Oliver Cromwell conducted two campaigns to subdue the Irish Catholics (1649-1650), and in the battles of Dunbar and Worcester (1650-1651) crushed the Scottish royalists, who had proclaimed King Charles II. , first-born of the executed sovereign.

The Rump Parliament change

After the execution of the King, a republic was declared, known as the Commonwealth of England. A Council of State was appointed to manage affairs, which included Cromwell among its members. His real power base was in the army.

Takeover of Ireland change

In 1652, Cromwell took over Ireland. Many historians believe that Cromwell committed an ethnic cleansing against the Irish Catholic people.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Cromwell wanted the Irish Catholics to move out of eastern Ireland into the northwest.[4] According to these historians, Cromwell and his army used massacres, starvation, and threats of execution to force the Irish to leave.[9][10][11] Historian Frances Stewart says that 600,000 Irish people – 43% of the Irish population – died from these policies.[11]

The Protectorate: 1653–1658 change

The House of Commons tried hard to control the army, but could not: in 1653, Cromwell dissolved the House of Commons, yielded legislative power to 139 people of his confidence and took the title of Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland, with powers wider than those enjoyed by the monarch. During his tenure he reorganized public finances, promoted the liberalization of commerce in order to ensure the prosperity of the mercantile bourgeoisie, promulgated the Navigation Act (1651), through which he imposed on the Netherlands the English maritime supremacy, defeated the United Provinces (1654), snatched Jamaica from Spain (1655), persecuted the Catholics and placed England at the head of the European Protestant countries.

A new constitution known as the Instrument of Government made Cromwell Lord Protector for life. He had the power to call and dissolve parliaments.

In 1657, Cromwell was offered the crown by Parliament. Cromwell thought about the offer for six weeks. Then he rejected it and was ceremonially re-installed as "Lord Protector" (with greater powers than had previously been granted him under this title) at Westminster Hall.

Cromwell is thought to have suffered from malaria (probably first contracted while on campaign in Ireland). He died at Whitehall on 3 September 1658, the anniversary of his great victories at Dunbar and Worcester.[12]

After Cromwell's death change

At his death (3 September 1658), however, the Republic was immersed in a period of chaos, which ended with the restoration of the monarchy in the person of Charles II of England by the Parliament (1660). Despite his prudence, the new monarch did not hesitate to order the exhumation of the corpse of the man who had signed the death sentence of his father, to cut off his head and expose it in the Tower of London.

He was succeeded as Lord Protector by his son Richard. Although Richard was not entirely without ability, he had no power base in either Parliament or the Army, and was forced to resign in the spring of 1659, bringing the Protectorate to an end. A year later Parliament restored Charles II as king.

When the Royalists returned to power, Cromwell's corpse was dug up, hung in chains, and beheaded. It is said that his head was lost for months until a soldier found it. His skull was passed around as a token until it was buried at Tyburn.

References change

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Adamson, John (1987). "The English Nobility and the Projected Settlement of 1647", in Historical Journal, 30, 3.

- Carlyle, Thomas (ed.) (1904 edition). Oliver Cromwell's letters and speeches, with elucidations [1] Archived 2006-11-02 at the Wayback Machine; [2] Archived 2012-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Coward, Barry (2003). The Stuart Age: England, 1603-1714. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-582-77251-9.

- Durston, Christopher (1998). The Fall of Cromwell's Major-Generals, in English Historical Review 1998 113(450): pp. 18–37, ISSN 0013-8266 .

- Gardiner, Samuel Rawson (1901). Oliver Cromwell, ISBN 978-1-4179-4961-8. [3] Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Gaunt, Peter (1996). Oliver Cromwell. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18356-3.

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Kenyon, John Philipps; Ohlmeyer, Jane H.; Morrill, John Stephen (2002). The Civil Wars: A Military History of England, Scotland, and Ireland 1638-1660. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-280278-1.

- Kishlansky, Mark (1990), "Saye What?" in Historical Journal 33, 4.

- Lenihan, Padraig (2001). Confederate Catholics at War, 1641-49. Cork University Press.

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Cromwell, Oliver (1989). Speeches of Oliver Cromwell. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-460-01254-6.

- Woolrych, Austin (1982). Commonwealth to Protectorate. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Woolrych, Austin (1987). Soldiers and Statesmen: The General Council of the Army and Its Debates, 1647-1648.

- Beales, Derek; Best, Geoffrey (2005). History Society Church. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02189-0.

- Worden, Blair (2002). Roundhead Reputations: The English Civil Wars and the Passions of Posterity. ISBN 978-0-14-100694-9.

- Worden, Blair (1977). The Rump Parliament 1648-53. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29213-9.

- Worden, Blair (2000). "Thomas Carlyle and Oliver Cromwell", in Proceedings Of The British Academy 105: pp. 131–170. ISSN 0068-1202 .

- Young, Peter (1999). The English Civil War. Da Capo Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-84022-222-7.

Footnotes change

- ↑ Dickens, Charles (1854). A Child's History of England volume 3. Bradbury and Evans. p. 239.

- ↑ "Cromwell, Oliver". Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ Norbrook, David (2000). Writing the English Republic: Poetry, Rhetoric and Politics, 1627-1660. Cambridge University Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-521-78569-3.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lutz, James M.; Lutz, Brenda J. (2004). Global Terrorism. Psychology Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-415-70051-5.

- ↑ Levene, Mark (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation-State. I.B.Tauris. pp. 55-57. ISBN 978-1-84511-057-4.

- ↑ Coogan, Tim Pat (2002). The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-312-29418-2.

- ↑ Axelrod, Alan (2003). Profiles in Leadership. Prentice Hall Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7352-0256-6.

- ↑ Ellis, Peter Berresford (2004). Eyewitness to Irish History. Wiley (TP). p. 108. ISBN 978-0-471-26633-4.

- ↑ Parliament of England (August 12, 1652). Act for the Settlement of Ireland. Constitution Society. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ↑ Morrill, John (December 2003). Rewriting Cromwell – A Case of Deafening Silences. Archived 2015-09-14 at the Wayback Machine Canadian Journal of History 38 (3): 553.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Stewart, Frances (2001). War and Underdevelopment. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-924187-3.

- ↑ Gaunt, p.204.

Bibliography change

Biographies change

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Ashley, Maurice (1958). The Greatness of Oliver Cromwell (Macmillan). [4] Archived 2012-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Bennett, Martyn (2006). Oliver Cromwell. Taylor & Francis US. ISBN 978-0-415-31922-5.

- Clifford, Alan C. (1999). Oliver Cromwell: The Lessons and Legacy of the Protectorate. ISBN 978-0-9526716-2-6.

- Davis, J.C. (2001). Oliver Cromwell. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-340-73118-5.

- Fraser, Antonia (2002). Cromwell: Our Chief of Men. ISBN 978-0-7538-1331-7.

- Firth, Charles Harding (2004). Oliver Cromwell and the Rule of the Puritans in England. Elibron Classics. ISBN 1-4021-4474-1.

- Gardiner, Samuel Rawson (1901). Oliver Cromwell, ISBN 978-1-4179-4961-8. Classic biography. [5] Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Gaunt, Peter (1996). Oliver Cromwell. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18356-3.

- Hill, Christopher (1970). God's Englishman: Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. London : Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Mason, James; Leonard, Angela (1998). Oliver Cromwell and the Civil War and Interregnum.

- Morrill, John (2004). "Cromwell, Oliver (1599–1658)", in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press) [6]

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Paul, Robert (1958). The Lord Protector: Religion And Politics In The Life Of Oliver Cromwell. [7] Archived 2012-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Smith, David Lee (2003). Cromwell and the Interregnum: The Essential Readings. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22725-0.

- Wedgwood, Cicely Veronica (1973). Oliver Cromwell. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Beales, Derek; Best, Geoffrey (2005). History Society Church. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02189-0.

Military studies change

- Durston, Christopher (2000). "'Settling the Hearts and Quieting the Minds of All Good People': the Major-generals and the Puritan Minorities of Interregnum England", in History 2000 85(278): pp. 247–267, ISSN 0018-2648 . Full text online at Ebsco.

- Durston, Christopher (1998). "The Fall of Cromwell's Major-Generals", in English Historical Review 1998 113(450): pp. 18–37, ISSN 0013-8266

- Firth, Charles Harding (1992). Cromwell's Army: A History of the English Soldier During the Civil Wars, the Commonwealth, and the Protectorate.

- Gillingham, John (1976). Cromwell: Portrait of a Soldier. London : Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-77148-7.

- Kenyon, John Philipps; Ohlmeyer, Jane H.; Morrill, John Stephen (2002). The Civil Wars: A Military History of England, Scotland, and Ireland 1638-1660. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-280278-1.

- Kitson, Frank (2004). Old Ironsides: The Military Biography of Oliver Cromwell. Weidenfeld & Nicolson Limited. ISBN 978-0-297-84688-8.

- Marshall, Alan (2004). Oliver Cromwell, Soldier: The Military Life of a Revolutionary at War. Brassey's. ISBN 978-1-85753-343-9.

- Woolrych, Austin (1990). "The Cromwellian Protectorate: a Military Dictatorship?" in History 1990 75(244): 207-231, ISSN 0018-2648 . Full text online at Ebsco.

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Young, Peter (1999). The English Civil War. Da Capo Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-84022-222-7.

Surveys of era change

- Coward, Barry (2002). The Cromwellian Protectorate. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4317-8.

- Coward, Barry (2003). The Stuart Age: England, 1603-1714. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-582-77251-9.

- Davies, Godfrey (1959). The Early Stuarts, 1603-1660. Oxford : Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821704-6.

- Korr, Charles P. (1975). Cromwell and the New Model Foreign Policy: England's Policy Toward France, 1649-1658. Berkeley : University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02281-2.

- Macinnes, Allan I. (2005). The British Revolution, 1629-60. Red Globe Press. ISBN 0-333-59750-8.

- Morrill, John Stephen; Adamson, J.S.A. (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman Publishing Group.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1967). Oliver Cromwell and his Parliaments, in his Religion, the Reformation and Social Change (Macmillan). online Archived 2008-09-02 at Archive-It

- Venning, T. (1995). Cromwellian Foreign Policy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-63388-5.

- Woolrych, Austin (1982). Commonwealth to Protectorate. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Worden, Blair (2002). Roundhead Reputations: The English Civil Wars and the Passions of Posterity. ISBN 978-0-14-100694-9.

Primary sources change

- Abbott, W.C. (ed.) (1937-47). Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell, 4 vols. The standard academic reference for Cromwell's own words. [8] Archived 2012-06-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- Carlyle, Thomas (ed.) (1904 edition), Oliver Cromwell's letters and speeches, with elucidations. [9] Archived 2006-11-02 at the Wayback Machine; [10] Archived 2012-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Haykin, Michael A. G. (ed.) (1999). To Honour God: The Spirituality of Oliver Cromwell (Joshua Press), Excerpts from Cromwell's religious writings.

- Morrill, John (1990). "Textualizing and Contextualizing Cromwell", in Historical Journal 1990 33(3): pp. 629–639. ISSN 0018-246X . Full text online at Jstor. Examines the Carlyle and Abbott editions.

- Cromwell, Oliver (1989). Speeches of Oliver Cromwell. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-460-01254-6.

- Worden, Blair (2000). Thomas Carlyle and Oliver Cromwell, in Proceedings Of The British Academy 105: pp. 131–170, ISSN 0068-1202 .

Other websites change

- The Cromwell Association

- The Cromwell Museum in Huntingdon Archived 2006-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Chronology of Oliver Cromwell World History Database Archived 2018-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Biography at the British Civil Wars & Commonwealth website Archived 2013-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

| Preceded by Charles I as King |

Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland | Succeeded by Richard Cromwell |