Caffeine

Caffeine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant. It is in the methylxanthine class. It is found in parts of plants, for example tea leaves and coffee beans. Its artificial form is also used in some soft drinks and energy drinks. It is the world's most popular psychoactive drug, and is legal in all of the world.[11]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /kæˈfiːn, ˈkæfiːn/ |

| Synonyms | Guaranine Methyltheobromine 1,3,7-Trimethylxanthine 7-methyltheophylline[6] Theine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Physical: low–moderate[1][2][3][4] Psychological: low[5] |

| Addiction liability | Low[4] / none[1][2][3] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, insufflation, enema, rectal, intravenous |

| Drug class | Stimulant |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 99%[8] |

| Protein binding | 25–36%[7] |

| Metabolism | Primary: CYP1A2[7] Minor: CYP2E1,[7] CYP3A4,[7] CYP2C8,[7] CYP2C9[7] |

| Metabolites | Paraxanthine (84%) Theobromine (12%) Theophylline (4%) |

| Onset of action | ~1 hour[8] |

| Elimination half-life | Adults: 3–7 hours[7] Infants (full term): 8 hours[7] Infants (premature): 100 hours[7] |

| Duration of action | 3–4 hours[8] |

| Excretion | Urine (100%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.329 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

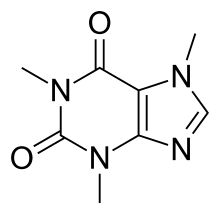

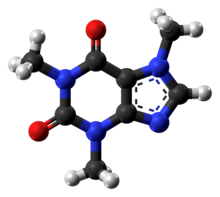

| Formula | C8H10N4O2 |

| Molar mass | 194.19 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.23 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 235 to 238 °C (455 to 460 °F) (anhydrous)[9][10] |

| |

| |

Sources

changeCaffeine is naturally found in the fruits, leaves and beans of coffee, cacao, guarana and tea plants.

The plants use caffeine as a pesticide. This is a chemical that kills insects if they eat the plant. It is the way the plant protects itself.

Caffeine was first extracted from cocoa beans into its purest form which is a white powder and the word originated from the German word “Kaffee” and the French word “café” which both mean caffeine.[12]

When it comes from the guarana plant it is called guaranine, when it comes from a tea plant, it is called theine, and in the mate drink it is called mateine (this drink is an infusion made with Yerba mate).

What caffeine is

changeCaffeine is a stimulant drug. A stimulant is a drug that increases body actions like heart rate, blood pressure, and metabolism. It makes a person more awake and alert.

Caffeine also is a diuretic. This means it makes a person make more urine (the waste liquid a person makes).

The caffeine chemical is called a xanthine alkaloid. This is a group of chemicals that are stimulants. Some xanthine alkaloids (like theophylline) are used to help asthma.

What caffeine is used for

changeThe biggest use of caffeine is as a stimulant. People drink coffee and other drinks with caffeine to stay awake.

In the beginning caffeine was found to relieve hunger, so it was used for weight loss. That did not last because people were using too much. Caffeine can be dangerous when not used in the right way.

Doctors sometimes use caffeine as a medicine.[13] It is added to analgesics (drugs used for pain).[13] This can improve their effect on headaches and other pain.[13] It is sometimes used to help premature babies (babies born very early) to breathe.[14] The short-term risk of this treatment seems to be that the babies treated gain less weight than usual.[15] Caffeine is sometimes given to people after a lumbar puncture.[16] This is when a needle is pushed between the bones of the lower back, normally to check for illnesses[16] like meningitis.[17]

Problems with caffeine

changeThe largest problem with caffeine is addiction. This is when people get bad symptoms when they do not have the drug. When people have withdrawal (feel bad because they do not have the drug) they drink more. This makes them feel better. But if they cannot get more, they are likely to feel some of the symptoms listed below:

- Headaches

- Being tired or need to sleep

- Caffeine inhibits sleep and in the long-term alters brain functions

- Sleep deprivation leads to a weakened connectivity between the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex which regulate mood and emotion.

- This causes the consumer to feel irritable, tired, restlessness, and anxious.

- Sleep deprivation leads to a weakened connectivity between the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex which regulate mood and emotion.

- Nausea (feeling like vomiting)

Caffeine can also hurt people if they drink a lot at once. If a person consumed 10-13 grams of caffeine quickly, between 80 and 100 cups of coffee, they would overdose and may even die.[18] Caffeine overdose is a medical diagnosis. It is called: Caffeine-Induced Organic Mental Disorder or Caffeine Intoxication. People with this can have these symptoms:

Caffeine helps for

changeCaffeine also has some strong advantages:[19]

- Lower risk of coronary disease

- Cut stroke risk

- Speed up metabolism

- Increases memory

- Helps ward off Alzheimer’s

- Reduces kidney stone risk

How much caffeine is safe

change250–300 mg of caffeine a day is a moderate amount. That is as much caffeine that is in three cups of coffee (8oz each cup). More than 750–1000 mg a day is a significant amount, but is very unlikely to kill someone. The Lethal Dose 50 of caffeine is 192 mg per kilogram, in rats. In humans, it is between 150 and 200 mg per kilogram (70-90 per pound.)

Caffeine is in many drinks and foods. This is approximate amounts of caffeine in some food and drink:

- Brewed coffee – 40 to 220 mg in a cup

- Instant coffee – 30 to 120 mg in a cup

- Decaffeinated coffee (with most caffeine taken out) – 3 to 5 mg in a cup

- Tea – 20 to 110 mg in a cup

- Soda drinks with caffeine – 36 to 90 mg in 12 ounces. Some people think that soft drinks which are light in color do not contain caffeine. This is not always true.

- Milk chocolate – 3 to 6 mg in an ounce

- Bittersweet chocolate – 25 mg in an ounce

One ounce – abbreviated oz – is 30 ml.

A 'cup' is 8 oz (240 ml.)

Different ways to get 200mg of caffeine

change| Caffeine equivalents[20][21] |

|---|

In general, each of the following contains approximately 200 milligrams of caffeine:

Notes: A fluid ounce is between 28 and 30 millilitres. a. There may also be large amounts of other chemicals, similar to caffeine in Chocolate and other products of cacao. There is theobromine in cacao, for example. These substances can have effects similar to those of caffeine. b. Most tea drunk in North America is not very strong. The figures are for this kind of tea. The tea drunk in most other places of the world is stronger; for these kinds of tea, the figures are probably too small. |

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Long-term caffeine use can lead to mild physical dependence. A withdrawal syndrome characterized by drowsiness, irritability, and headache typically lasts no longer than a day. True compulsive use of caffeine has not been documented.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Karch SB (2009). Karch's pathology of drug abuse (4th ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-8493-7881-2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

Substance use disorder in DSM-5 combines the DSM-IV categories of substance abuse and substance dependence into a single disorder measured on a continuum from mild to severe. ... Additionally, the diagnosis of dependence caused much confusion. Most people link dependence with "addiction" when in fact dependence can be a normal body response to a substance. ... DSM-5 will not include caffeine use disorder, although research shows that as little as two to three cups of coffee can trigger a withdrawal effect marked by tiredness or sleepiness. There is sufficient evidence to support this as a condition, however it is not yet clear to what extent it is a clinically significant disorder.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Introduction to Pharmacology (third ed.). Abingdon: CRC Press. 2007. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-1-4200-4742-4.

- ↑ Juliano LM, Griffiths RR (October 2004). "A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features". Psychopharmacology. 176 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. ISSN 0033-3158. PMID 15448977. S2CID 5572188.

- ↑ "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 "Caffeine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Poleszak E, Szopa A, Wyska E, Kukuła-Koch W, Serefko A, Wośko S, Bogatko K, Wróbel A, Wlaź P (February 2016). "Caffeine augments the antidepressant-like activity of mianserin and agomelatine in forced swim and tail suspension tests in mice". Pharmacological Reports. 68 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2015.06.138. PMID 26721352. S2CID 19471083.

- ↑ "Caffeine". Pubchem Compound. NCBI. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Boiling Point

178 °C (sublimes)

Melting Point

238 DEG C (ANHYD) - ↑ "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Experimental Melting Point:

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar

237 °C Oxford University Chemical Safety Data

238 °C LKT Labs [C0221]

237 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 14937

238 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 17008, 17229, 22105, 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235.25 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

236 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 6603

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar A10431, 39214

Experimental Boiling Point:

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar 39214 - ↑ Burchfield G (1997). Meredith H (ed.). "What's your poison: caffeine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ "History and Background". Caffeine. 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Caffeine". The Nutrition Source. 2020-07-30. Retrieved 2024-12-27.

- ↑ Moschino, Laura; Zivanovic, Sanja; Hartley, Caroline; Trevisanuto, Daniele; Baraldi, Eugenio; Roehr, Charles Christoph (2020-03-01). "Caffeine in preterm infants: where are we in 2020?". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2024-12-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Schmidt, B; Roberts, RS; Davis, P; Doyle, LW (May 18, 2006). "Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (20): 2112–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054065. PMID 16707748. S2CID 22587234.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Lumbar Puncture - What You Need to Know". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2024-12-27.

- ↑ "What is a lumbar puncture?". www.meningitis.org. Retrieved 2024-12-27.

- ↑ "Can caffeine kill you?". Livescience.com. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ "The Advantages and Disadvantages Of Drinking Coffee | Coffee Corner". Coffee Corner. 2017-10-26. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- ↑ "Caffeine Content of Food and Drugs". Nutrition Action Health Newsletter. Center for Science in the Public Interest. December 1996. Archived from the original on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ "Caffeine Content of Beverages, Foods, & Medications". The Vaults of Erowid. July 7, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

Other websites

changeScientific information

change- eMedicine Caffeine-Related Psychiatric Disorders

- The Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs, Caffeine-Part 1 Part 2

- The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Caffeine: A User's Guide Archived 2008-06-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Caffeine: Psychological Effects, Use & Abuse Archived 2007-04-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Caffeine Withdrawal Recognized as a Disorder Archived 2010-08-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Is Caffeine a Health Hazard?

Others

change- Caffeine Withdrawal Symptoms Archived 2021-10-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Caffeine: How Stuff Works

- Caffeine: The most popular psychoactive drug, Broke but Shredded, January 2022 Archived 2022-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Erowid Caffeine Vaults

- #caffeine! - The Caffeine Information Archive Archived 2008-02-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Naked Scientists Online: Why do plants make caffeine?

- Alcohol and Drugs History Society: Caffeine news page

- Coffee: A Little Really Does Go a Long Way, NPR, September 28, 2006

- Does coffee really give you a buzz? by John Triggs in the Daily Express April 17 2007

- Burgower, Rachael. “The Effects of Energy Drinks on Sleep and Daily Functioning.” , 2014, pp. 1–59. ProQuest 1642026146

News

change- National Post: Caffeine linked to psychiatric disorders Archived 2010-08-22 at the Wayback Machine