Developmental biology

Developmental biology is the study of how organisms grow and develop.

Modern developmental biology studies the genetic control of cell growth, differentiation and morphogenesis.[1] These are the processes which turn a zygote into an adult animal.

Cell differentiation

changeDifferentiation is the formation of cell types, from what is originally one cell – the zygote or spore. The formation of cell types like nerve cells occurs with a number of intermediary, less differentiated cell types. A cell stays a certain cell type by maintaining a particular pattern of gene expression.[2]293-5 This depends on regulatory genes.

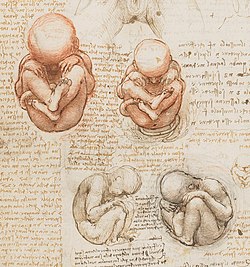

Embryonic development

changeEmbryogenesis is the step in the life cycle after fertilisation – the development of the embryo, starting from the zygote (fertilised egg). Organisms can differ drastically in the how embryo develops, especially when they belong to different phyla.

Growth

changeGrowth is the enlargement of a tissue or organism. Growth continues after the embryonic stage, and occurs through cell division, enlargement of cells or accumulation of extracellular material. In plants, growth results in an adult organism that is strikingly different from the embryo. The dividing cells tend to be distinct from differentiated cells (see stem cell).

In some tissues dividing cells are restricted to special areas, such as the growth plates of bones.[2]467-482 But some stem cells move to where they are needed, from the bone marrow to form muscle, bone or adipose (fat) tissue.[3]

Metamorphosis

changeMany animals have a larval stage, with a body plan different from that of the adult organism. The larva abrubtly develops into an adult in a process called metamorphosis. For example, caterpillars (butterfly larvae) are specialized for feeding whereas adult butterflies (imagos) are specialised for flight and reproduction. When the caterpillar has grown enough, it turns into an immobile pupa. Here, the imago develops from imaginal discs found inside the larva.[4]575-585

Regeneration

changeRegeneration is the reactivation of development so that a missing body part grows back. This phenomenon has been studied particularly in salamanders, where the adults can reconstruct a whole limb after it has been amputated.[4] Researchers hope to one day be able to induce regeneration in humans.[5] There is little spontaneous regeneration in adult humans, although the liver is a notable exception. Like for salamanders, the regeneration of the liver involves reversing some cells to an earlier state.[4]592-601

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ Morphogenesis gives rise to tissues, organs and anatomy.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wolpert, Lewis; Beddington R, Jessell T, Lawrence P, Meyerowitz E, Smith J (2002). Principles of development (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-879291-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Chamberlain G; Fox J; Ashton B; Middleton J (November 2007). "Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing". Stem Cells. 25 (11): 2739–49. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. PMID 17656645. S2CID 21930628.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gilbert SF (2003). Developmental biology (7th ed.). Sinauer. ISBN 0-87893-258-5.

- ↑ Stocum DL (December 2002). "Development. A tail of transdifferentiation". Science. 298 (5600): 1901–3. doi:10.1126/science.1079853. PMID 12471238. S2CID 83325083.