Riot Act

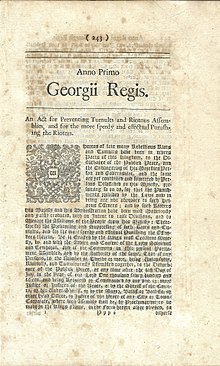

The Riot Act (1 Geo. 1. St. 2. c. 5), sometimes called the Riot Act 1714[2] or the Riot Act 1715,[3] was an act of the Parliament of Great Britain. It gave local authorities power to declare any group of 12 or more people to be unlawfully assembled and order them to disperse or be punished. The act's full title was "An Act for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies, and for the more speedy and effectual punishing the rioters". It came into force on 1 August 1715.[4] It was repealed in England and Wales by section 10(2) and Part III of Schedule 3 of the Criminal Law Act 1967. Acts like it were part of the laws of British colonies in Australia and North America, some of which remain in force today.

| |

| Long title | An Act for Preventing Tumults and Riotous Assemblies, and for the more speedy and effectual Punishing the Rioters |

|---|---|

| Citation | 1 Geo. 1. St. 2. c. 5 |

| Dates | |

| Commencement | 1 August 1715 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Criminal Law Act 1967 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

The phrase "read the riot act" means a warning of consequences.

It was introduced during a time of riots in England.[5] The preamble makes reference to "many rebellious riots and tumults [that] have been [taking place of late] in diverse parts of this kingdom", adding that those involved "presum[e] so to do, for that the punishments provided by the laws now in being are not adequate to such heinous offences".[5]

Proclamation of riotous assembly

changeLocal officials could make an announcement ordering the dispersal of any group of twelve or more people who were "unlawfully, riotously, and tumultuously assembled together". If the group failed to disperse within one hour, then anyone remaining gathered was guilty of a felony without benefit of clergy, punishable by death.[5] This could be made in an incorporated town or city by the mayor, bailiff or "other head officer", or a justice of the peace. Elsewhere it could be made by a justice of the peace or the sheriff, undersheriff or parish constable. It had to be read out to the gathering concerned and had to follow precise wording detailed in the act; several convictions were overturned because some words had been left out, in particular "God save the King".[6]

The wording that had to be read out to the assembled gathering was as follows:

Our sovereign lord the King chargeth and commandeth all persons, being assembled, immediately to disperse themselves, and peaceably to depart to their habitations, or to their lawful business, upon the pains contained in the act made in the first year of King George, for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies. God save the King.

In a number of jurisdictions, such as Britain, Canada and New Zealand, these words were put in the law itself. In New Zealand's Crimes Act 1961, section 88, repealed since 1987, was specifically given the heading of "Reading the Riot Act".[7]

References

change- ↑ This short title was conferred by the Short Titles Act 1896, section 1 and the first schedule.

- ↑ Turner, J. W. Cecil (1964) [1962]. Kenny's Outlines of Criminal Law (18th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. lvii.

- ↑ St Clair Feilden, H.; Gray Etheridge, W. (1895). A Short Constitutional History of England (3rd ed.). B H Blackwell. Oxford. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. p. 335.

- ↑ Stevenson, John (6 June 2014). Popular Disturbances in England 1700-1832. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 9781317897149. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Cite error: The named reference

:0was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ The Legal observer, or, Journal of jurisprudence. Vol. 2. J. Richards. 1831. p. 32. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ↑ "Crimes Act 1961, Public Act 88". New Zealand Legislation. New Zealand Government. Retrieved 30 July 2018.