Sickle cell disease

Sickle cell anaemia is a genetic disease. It affects red blood cells. It changes the cells from flexible disks into rigid crescents. When many red cells take this shape veins get blocked. This can cause damage to many organs. The organ damage increases with time and leads to an early death.

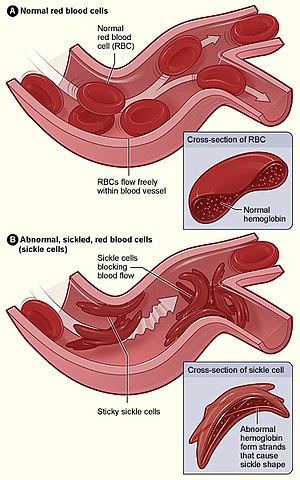

Lower Figure (B) shows abnormal, sickled red blood cells piling up in a vein.

The disease

changeThis is a lifelong disease which starts in childhood. The red blood cells take up an abnormal, rigid, sickle shape. The cells also become sticky. This causes difficult blood flow when cells flow through long narrow capillaries. Low oxygen increases the problem. As they pass through low oxygen areas most cells take up this shape. The cells then stick to the inner wall of blood vessels, especially the branching point of veins. This leads to a blockade of blood flow in many organs. Severe complications may result.

The classic example of a sickle cell crisis is "acute chest syndrome"(ACS). This is unique to sicklers, and can cause death in a day or two unless treated. Historically, acute chest syndrome was considered different from infection (pneumonia). But in treatment there is not much point making that distinction.[1]

ACS is a clinical diagnosis helped by at least one chest X-ray. In all other organs low oxygen causes widening of blood vessels. But the lung is a unique organ where blood vessels become narrower when oxygen is low. This unique problem makes the lung a major target of the disease. Fever is the most common symptom of ACS in children because infection is more common. In the adults circulating clots and broken pieces of bone marrow can also add to the blockage of vessels in the lung and lead to ACS. ACS can be partially treated by blood transfusion to dilute the sickled cells with some normal red blood cells. An even better treatment is a procedure called red blood cell exchange. Automated apheresis machines can do RBC exchange.

A milder and more frequent problem is 'painful crisis'. Painful crisis involves flank, back and thigh pains that can be relieved by treatment. A painful crisis may evolve into worse problems such as acute chest and other organ failures e.g. strokes, heart attacks. Both strokes and heart attacks are general problems which may happen in older people. But in sickle patients these can happen even in the young.

The spleen is involved differently in different ethnic groups with this disease. Spleen is the organ which filters old RBCs and destroys them. Old RBCs are stiff and cannot pass through some very narrow slits in the spleen. But in sickle patients all cells very quickly become stiff and thus keep clogging up the spleen. Starting from a very young age segments of the spleen die because of this problem. In the pure form of this disease the whole spleen is dead and shrunken before the patient become adult. Normal spleen keeps a large store of B cells which make antibodies and protect us from bacteria. Loss of a working spleen leads to loss of protection from such bacteria.

In many Asian populations beta thalassaemia occurs together with sickle cell disease. Thalassemia itself is another form of anaemia. But the nature of the two disease are opposite. Thalassemia increases red cell flexibility. However, thalassemia itself can be a serious disease.

Population genetics

changeThe sickling occurs because of a single point mutation in the gene for the beta chain of haemoglobin. Sickle-cell disease occurs more commonly in people (or their descendants) from parts of tropical and sub-tropical regions where malaria is or was common. One quarter of all people of Sub-Saharan African origin carry the gene.

We all inherit two copies (alleles) of the hemoglobin beta gene. One comes each parent. Some people are heterozygous: they have the sickle mutation in one copy and the other copy is normal. Such people are called sickle trait or a carrier. People with sickle trait are more resistant to malaria than normal people.[2]

When both alleles of a gene are similar (homozygous) a person has copies mutated or both normal. If both alleles have the mutation, it causes the full disease. In malaria prone areas, normal people die frequently of malaria often before they had children. Those with both copies with sickle mutation die of sickle disease before they can reproduce. But the heterozygotes have a better survival (and have more children) than both homozygous groups. Thus, the inheritance of the disease is an example of 'heterozygous advantage'.

In the full (homozygous) disease life expectancy is shortened, in fact it is near-fatal in pre-modern societies. Sir Cyril Clarke said (referring to East Africa in the 1960s) "Almost all the children (with sickle-cell disease) will die in infancy".[3]p25. Studies in the modern U.S.A. report an average life expectancy of 42 years for males and 48 years for females.[4]

References

change- ↑ N Engl J Med. 2000 Jun 22;342(25):1855-65. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM200006223422502

- ↑ Wellems TE, Hayton K, Fairhurst RM (September 2009). "The impact of malaria parasitism: from corpuscles to communities". J. Clin. Invest. 119 (9): 2496–505. doi:10.1172/JCI38307. PMC 2735907. PMID 19729847.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Clarke, Sir Cyril A. 1970. Human genetics and medicine. Arnold, London.

- ↑ Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF; et al. (June 1994). "Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death". N. Engl. J. Med. 330 (23): 1639–44. doi:10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 7993409. Archived from the original on 2010-01-05. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)