Spacetime

Spacetime or space–time is a mathematical model that joins space and time into a single idea called a continuum. This four-dimensional continuum is known as Minkowski space.

Combining these two ideas helped cosmology to understand how the universe works on the big level (e.g. galaxies) and small level (e.g. atoms).

In non-relativistic classical mechanics, the use of Euclidean space instead of space–time is good, because time is treated as universal with a constant rate of passage which is independent of the state of motion of an observer.

But in a relativistic universe, time cannot be separated from the three dimensions of space. This is because the observed rate at which time passes depends on an object's velocity relative to the observer. Also, the strength of any gravitational field slows the passage of time for an object as seen by an observer outside the field.

Further aspects

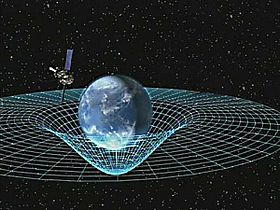

changeWherever matter exists, it bends the geometry of spacetime. This results in a curved shape of spacetime which can be understood as gravity. The white lines on the picture on the right represent the effect of mass on spacetime.

In classical mechanics, the use of spacetime is optional, as time is independent of motion in the three dimensions of Euclidean space. However, when a body is moving at speeds close to the speed of light (relativistic speeds), time cannot be separated from the three dimensions of space. Time, from the point of view of a stationary observer,[1] depends on how close to the speed of light the object is moving.[2]

Historical origin

changeMany people link spacetime with Albert Einstein, who proposed special relativity in 1905. However, it was Einstein's teacher, Hermann Minkowski, who suggested spacetime, in a 1908 essay.[3] His concept of Minkowski space is the earliest treatment of space and time as two aspects of a unified whole, which is the essence of special relativity. He hoped this new idea would clarify the theory of special relativity.

Minkowski spacetime is only accurate at describing constant velocity. It was Einstein, though, who discovered the curvature of spacetime (gravity) in general relativity. In general relativity, Einstein generalized Minkowski spacetime to include the effects of acceleration. Einstein discovered that the curvature in his 4-dimensional spacetime representation was actually the cause of gravity.

The 1926 thirteenth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica included an article by Einstein titled "space–time".[2]

Literary background

changeEdgar Allan Poe wrote an essay on cosmology titled Eureka (1848) which said that "space and duration are one". This is the first known instance of suggesting space and time to be different perceptions of one thing. Poe arrived at this conclusion after approximately 90 pages of reasoning but employed no mathematics.[4]

In 1895, H.G. Wells in his novel, The Time Machine, wrote, “There is no difference between Time and any of the three dimensions of Space except that our consciousness moves along it”. He added, “Scientific people…know very well that Time is only a kind of Space”.[5]

Spacetime in quantum mechanics

changeIn general relativity, spacetime is thought of as smooth and continuous. However, in the theory of quantum mechanics, spacetime is not always continuous.

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ Einstein, Albert and Infeld, Leopold 1938. The evolution of physics: from early concept to relativity and quanta. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Einstein, Albert, 1926, "Space-Time," Encyclopedia Britannica, 13th ed.

- ↑ Hermann Minkowski, "Raum und Zeit", 80. Versammlung Deutscher Naturforscher (Köln, 1908). Physikalische Zeitschrift 10 104-111 (1909) and Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung 18 75-88 (1909). For an English translation, see Lorentz et al. (1952).

- ↑ Poe, Edgar A. (1848). Eureka: an essay on the material and spiritual universe. Hesperus Press Limited. ISBN 1-84391-009-8.

- ↑ Wells, H.G. (2004). The Time Machine. New York: Pocket Books. (pp. 5; 6)

- Lorentz H.A; Einstein, Albert; Minkowksi, Hermann and Weyl, Hermann 1952. The principle of relativity: a collection of original memoirs. Dover.

- Lucas, John Randolph 1973. A treatise on time and space. London: Methuen.