The Author's Farce

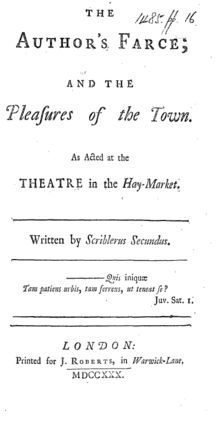

Henry Fielding wrote the play The Author's Farce and the Pleasures of the Town. It was first acted on 30 March 1730 in the Haymarket Theatre. The play responds to the rejection of Fielding's early plays and was his first success.

Harry Luckless is the main character of the play. He tries to write a play in the first act and completes the play in the second act. It is a puppet play called "The Pleasures of the Town". Many theatres do not accept the play but it is later shown within the third act. The play is about the puppet character Goddess Nonsense who wants a husband. The end of The Author's Farce combines the characters of the puppet play and the main play for humour.

Fielding became a popular writer in London after The Author's Farce. The Haymarket Theatre let him experiment with his plays and Fielding changed the comedy genre. The puppet play within the main play made fun of other London plays. The Author's Farce was first a success. Then, it was ignored by critics until the 20th century. Critics focused on the play's effects on Fielding's work.

Plot

changeThe Author's Farce has three acts. The play begins with Harry Luckless wanting a relationship with his landlady's daughter Harriot. Also, he is a writer and he is writing a play. The start of the play is like Fielding's other plays but the rest of the play is different.[1] Luckless wants to be a good writer but he cannot make money. Other people want to give Luckless money but he does not want it. When Luckless's friend Witmore pays Luckless's rent, Luckless steals the money back. In the second act, Luckless asks for help to finish his puppet play "The Pleasures of the Town". However, people give him bad advice and theatres reject the play. Later, a theatre shows the play.[2] The third act is the puppet play. The puppets are acted by real people and not puppets.[3]

The third act is the puppet play and is a play within a play. It takes place along the River Styx and starts with the Goddess of Nonsense wanting a husband. There are many possible husbands there and they are stupid. They are Dr Orator, Sir Farcical Comic, Mrs Novel, Bookseller, Poet, Monsieur Pantomime, Don Tragedio, and Signior Opera.[4] She selects Signior Opera after he sings for her. He is an opera signior and a castrato. Mrs Novel claims that she and Signior Opera had a child.[5] This makes the Goddess of Nonsense angry but she forgives Signior Opera. The puppet play is stopped by the characters Constable and Murdertext. They want to arrest Luckless for hurting the Goddess of Nonsense. Mrs Novel asks for the play to be completed and they agree. However, a person from the land of Bantam stops the play and says that Luckless is the prince of Bantam. Another messenger comes and says that the King of Bantam died and Luckless is the new king. Luckless is told that his landlady is the Queen of Old Brentford and her daughter Harriot is a princess.[4] The play ends with four poets saying how they would end the play. They are stopped by a cat that looks like a person. The cat person ends the play.[6]

Meaning

changeThe Author's Farce show parts of Fielding's life and experience with the London theatre community.[7] Some of his other plays were rejected from the Theatre Royal.[8] The Author's Farce was put on at a small theatre. This allowed Fielding to experiment. He could not experiment at larger theatres.[9] The play was the first to have things found in his later plays. However, he did not come up with them all. He got many of his ideas from the Scriblerus Club. Their members were Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, John Gay, and John Arbuthnot.[10] One idea is his character Nonsense. She is similar to Pope's character Dulness in the Dunciad.[11] Both characters promote bad writing. Fielding gave Nonsense a sexual aspect. It is funny when she chooses as a lover a man who is sexless.[12] Other parts of the play are similar to Gay's Beggar's Opera.[13]

The play is a farce. Farces use slapstick and physical humour to be funny. They also use absurd plots. A farce also makes serious situations funny.[14] Fielding thought that theatre was becoming bad. He mocked theatre and theatre audiences in his play.[15] His character Luckless states that for someone to become successful they must write nonsense.[16] His only desire is to make money. Other characters feel that money is all that matters. They do not care about good writing. Even Harriot believes that a good lover is one who is rich.[17] Fielding made the same claims about people when he attacked Samuel Richardson's novel, Pamela.[18]

The ending of the play merges real and fake.[19] Fielding defends an old view of writing. He also attacks new types of writing. He uses puppets to represent various genres.[20] He made fun of people liking Italian opera.[21] The puppet character Signior Opera is a castrato. Castratos are men without testicles. The character Nonsense wants him as a lover. Mrs Novel says that Signior Opera had a baby with her. However, Signior Opera can't have sex or have babies. Fielding is mocking how women like Italian opera singers. Other writers mocked Italian opera singers. William Hogarth says the castratos are related to politics.[22] Many other writers make fun of women who favour castratos.[23]

Background

changeThe play uses characters and ideas from Fielding's life.[8] The characters Marplay and Sparkish manage the theatre. They offer Luckless poor advice on how to write a play. Then also reject Luckless's play. This is what Colley Cibber and Robert Wilks did to Fielding. They rejected his play The Temple Beau. When Wilks died Fielding changed the play. He removed Sparkish. He added a character like Theophilus Cibber, the son of Colley. The character was like Theopilus during the Actor Rebellion of 1733.[24]

Luckless and Mrs. Moneywood is similar to Fielding with Jan Oson. Oson was his landlord during 1729. When staying with Oson, Fielding owed a lot of money. Fielding fled to London and Oson took his property to pay for the debt. Mrs Moneywood does the same in the play.[25] Characters in the puppet play are based on real people. Mrs Novel is Eliza Haywood. Signior Opera is Senesino.[26] Bookweight is similar to Edmund Curll.[27] Orator is John Henley. Monsieur Pantomime is John Rich. Don Tragedio is Lewis Theobald. Sir Farcical Comick is of Colley Cibber as an actor.[28]

Fielding also used literary sources. His plot is like George Farquhar's Love and a Bottle (1698). Both talk about a writing and a landlady. They have many differences.[29] Fielding took from the writing of the Scriblerus Club and other plays. Luckless's life is similar to characters in John Dryden's The Rehearsal (1672), Farquhar's Love and a Bottle (1698), James Ralph's The Touch-Stone (1728), and Richard Savage's An Author to be Lett (1729). The play has similar ideas to Dunciad Variorum. He also borrowed from Gay's Three Hours after Marriage (1717) and The Beggar's Opera (1728).[30] Fielding's play also influenced other works. They included the revised Dunciad and Gay's The Rehearsal at Goatham.[31]

Response

changeThe play was successful. Fielding became a popular writer.[32] It was shown with Tom Thumb. That helped it be liked. The Pleasures of the Town was the most liked part. The Daily Post newspaper said it was approved by all. A newspaper that didn't like Fielding also said that the play was liked. Many well-known people and royalty in Britain saw the show.[33] John Perceval, 1st Earl of Egmont said that the play was "full of humour, with some wit."[34] The play was rarely mentioned later in the 18th century. This was true in the 19th century. The play was printed again a few times. Leslie Stephen and Austin Dobson studied the play. They looked at what the play said about Fielding's life.[35]

20th-century critics agreed with Dobson. Many of the critics like Charles Woods talked about the play as part of Fielding's writing career. He also said the work was not political. Later critics agreed with Woods.[36] Many modern critics approved of the play. They are Wilbur Cross,[37] Frederick Homes Dudden,[38] Ian Donaldson,[39] Pat Rogers,[40] Robert Hume,[41] Martin and Ruthe Battestin,[42] Harold Pagliaro,[43] and Thomas Lockwood.[44] Some critics liked the play but not all of it. They are J. Paul Hunter,[45] Matthew Kinservik,[46]

Stage history

changeHenry Fielding wrote The Author's Farce in 1729. It was made after the Theatre Royal rejected his plays.[29] Advertisements were put in the 18 March 1730 Daily Post and in the 21 March 1730 Weekly Medley and Literary Journal. They said that actors were practicing the play. An advertisement in the 23 and 26 Daily Post said the play would have a puppet play. The advertisement also said prices will be high. That suggests that the play would be popular. The first show was on 30 March 1730, Easter Monday. It took place at the Little Theatre and was shown 41 times. On 6 April 1730, the play The Cheats of Scapin was shown with it.[47]

Fielding changed The Author's Farce. The new play was shown on 21 April 1730 with Fielding's play Tom Thumb. They were shown together in May and June 32 times. They were shown again on 3 July 1730. On 1 August 1730, the last act of the play was shown for the Tottenham Court fair. An advertisement in the Daily Post on 17 October 1730 said the play had a new prologue. The changed play was shown on 21 October. It was changed again then it was replaced by the play The Beggar's Wedding by Charles Coffey. The play came back on 18 November 1730. Only the first and second act were shown between November and January. During this time, it was shown with the play Damon and Phillida. Damon and Phillida was stopped and the play The Jealous Taylor was added on 13 January 1731. The Author's Farce was shown from January to March 1731. It was shown again with a new prologue on 10 May 1731. The new prologue is now gone.[48]

The Author's Farce was shown with The Tragedy of Tragedies on 31 March 1731. They were shown 6 times. The last regular show at the Little Theatre was 18 June 1731. It was shown one time on 12 May 1732. The last show of The Author's Farce as a regular play was on 28 March 1748. Theophilus Cibber ran the show. The last act "Pleasures of the Town" was shown on its own. It was shown 16 times at Norwich after 1749. Also, it was shown at York in 1751 to 1752.[49] The whole play was acted by puppets many times. Thomas Yeates had puppet shows called Punch's Oratory, or The Pleasures of the Town after 1734.[50]

Fielding changed The Author's Farce at the end of 1733. He added a new prologue and epilogue. Fielding changed it after the Actor Rebellion of 1733. The 8 January 1734 Daily Journal had an advertisement. It said The Author's Farce would be shown at the Theatre Royal. It was shown six times. The cast was not as good as the first cast. It was shown 4 times with the play The Intriguing Chambermade and 2 times with the play The Harlot's Progress. The changed The Author's Farce was printed with The Intriguing Chambermade and a letter written by an unknown author.[51] The changed The Author's Farce was printed again in 1750 until 1966.[29] Arthur Murphy printed the play in 1762 in Works of Henry Fielding. George Saintsbury printed the play in 1893 in Works of Henry Fielding. G. H. Maynadier printed act one and two in 1903 in Works of Henry Fielding.[52]

Cast

change1730 cast

changePlay:[53]

- Harry Luckless – playwright, played by Mr. Mullart (William Mullart)

- Harriot Moneywood – daughter of Mrs. Moneywood, played by Miss Palms

- Mrs Moneywood – Luckless's landlady, played by Mrs. Mullart (Elizabeth Mullart)

- Witmore – played by Mr. Lacy (James Lacy)

- Marplay – played by Mr. Reynolds

- Sparkish – played by Mr. Stopler

- Bookweight – played by Mr. Jones

- Scarecrow – played by Mr. Marshal

- Dash – played by Mr. Hallam

- Quibble – played by Mr. Dove

- Blotpage – played by Mr. Wells junior

- Jack – Luckless's servant, played by Mr. Achurch

- Jack-Pudding – played by Mr. Reynolds

- Bantomite – played by Mr. Marshal

Internal puppet show:[54]

- Player – by Mr. Dove

- Constable – by Mr. Wells

- Murder-text – by Mr. Hallam

- Goddess of Nonsense – by Mrs. Mullart

- Charon – by Mr. Ayres

- Curry – by Mr. Dove

- A Poet – by Mr. W. Hallam

- Signior Opera – by Mr. Stopler

- Don Tragedio – by Mr. Marshal

- Sir Farcical Comick – by Mr. Davenport

- Dr. Orator – by Mr. Jones

- Monsieur Pantomime – by Mr. Knott

- Mrs. Novel – by Mrs. Martin

- Robgrave – by Mr. Harris

- Saylor – by Mr. Achurch

- Somebody – by Mr. Harris junior

- Nobody – by Mr. Wells junior

- Punch – by Mr. Hicks

- Lady Kingcall – by Miss Clarke

- Mrs. Cheat'em – by Mrs. Wind

- Mrs. Glass-rin – by Mrs. Blunt

- Prologue spoken by Mr. Jones[55]

- Epilogue spoken by four poets, a player and a cat

- 1st Poet – played by Mr. Jones

- 2nd Poet – played by Mr. Dove

- 3rd Poet – played by Mr. Marshall

- 4th Poet – played by Mr. Wells junior

- Player – played by Miss Palms

- Cat – played by Mrs. Martin

1734 changed cast

changePlay:[56]

- Index – unlisted actor

Internal puppet show:[57]

References

change- ↑ Rivero 1989 pp. 35–36

- ↑ Pagliaro 1999 pp. 70–71

- ↑ Rivero 1989 pp. 37

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Pagliaro 1999 pp. 71–72

- ↑ Campbell 1995 p. 33

- ↑ Hunter 1975 p. 54

- ↑ Pagliaro 1999 pp. 69–70

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Koon 1986 p. 123

- ↑ Rivero p. 23

- ↑ Rivero 1989 pp. 31–34

- ↑ Pagliaro 1999 p. 71

- ↑ Campbell 1995 pp. 32–34

- ↑ Warner 1998 p. 242

- ↑ Rivero pp. 38–41

- ↑ Freeman 2002 pp. 59–63

- ↑ Fielding 1967 p. 16

- ↑ Rivero pp. 33–37

- ↑ Warner 1998 p. 241

- ↑ Freeman 2002 pp. 64–65

- ↑ Ingrassia 2004 pp. 21–22

- ↑ Roose-Evans 1977 p. 35

- ↑ Campbell 1995 pp. 33–34

- ↑ Campbell 1995 pp. 32–36

- ↑ Pagliaro 1999 p. 70

- ↑ Battestin and Battestin 1993 pp. 72–73

- ↑ Freeman 2002 pp. 62–63

- ↑ Rawson 2008 p. 23

- ↑ Hume 1988 p. 64

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Hume 1988 p. 63

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 189–190

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 205

- ↑ Rivero 1989 p. 31

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 194–195

- ↑ Fielding 2004 qtd p. 204

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 205–206

- ↑ Lockwood 2004 pp. 206–207

- ↑ Cross 1918 p. 80

- ↑ Dudden 1966 p. 54

- ↑ Donaldson 1970 p. 194

- ↑ Rogers 1979 p. 49

- ↑ Hume 1988 pp. 63–65

- ↑ Battestin and Battestin 1993 p. 83

- ↑ Pagliaro 1998 p. 69

- ↑ Lockwood 2004 p. 212

- ↑ Hunter 1975 p. 53

- ↑ Kinservik 2002 p. 68

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 192–193

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 194–196

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 196–197

- ↑ Speaight 1990 p. 157

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 294–299

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 204–206

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 227

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 227–228

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 222

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 304

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 305

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 297

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 299

Sources

change- Bateson, Frederick. English Comic Drama 1700–1750. New York: Russell & Russell, 1963. OCLC 350284.

- Battestin, Martin, and Battestin, Ruthe. Henry Fielding: A Life. London: Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0415014387

- Campbell, Jill. Natural Masques: Gender and Identity in Fielding's Plays and Novels. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0804723915

- Cross, Wilbur. The History of Henry Fielding. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1918. OCLC 313644743.

- Donaldson, Ian. The World Upside Down: Comedy from Jonson to Fielding. Oxford: Clarendon, 1970. ISBN 0198116942

- Dudden, F. Homes. Henry Fielding: His Life, Works and Times. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1966. OCLC 173325.

- Fielding, Henry. The Author's Farce. London: Edward Arnold, 1967. OCLC 16876561.

- Fielding, Henry. Plays Vol. 1 (1728–1731). Ed. Thomas Lockwood. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2004. ISBN 0199257892

- Freeman, Lisa. Character's Theatre. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002. ISBN 0812236394

- Hume, Robert. Fielding and the London Theater. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. ISBN 0198128649

- Hunter, J. Paul. Occasional Form. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. ISBN 0801816726

- Ingrassia, Catherine. Anti-Pamela and Shamela. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2004. ISBN 155111383X

- Ingrassia, Catherine. Authorship, Commerce, and Gender in Early Eighteenth-Century England. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0521630630

- Kinservik, Matthew. Disciplining Satire. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2002. ISBN 0838755127

- Koon, Helene. Colley Cibber: A Biography. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1986. OCLC 301354330.

- Pagliaro, Harold. Henry Fielding: A Literary Life. New York: St Martin's Press, 1998. ISBN 0312210329

- Rawson, Claude. Henry Fielding (1707–1754). Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2008. ISBN 9780874139310

- Rivero, Albert. The Plays of Henry Fielding: A Critical Study of His Dramatic Career. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989. ISBN 0813912288

- Rogers, Pat. Henry Fielding, A Biography. New York: Scribner, 1979. ISBN 0684162644

- Roose-Evans, James. London Theatre: From the Globe to the National. Oxford: Phaidon, 1977. ISBN 071481766X

- Speaight, George. The History of the English Puppet Theatre. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1990. ISBN 0809316064

- Warner, William. Licensing Entertainment: the Elevation of the Novel Reading in Britain, 1684–1750. ISBN 0520201809

- Woods, Charles. "Introduction" in The Author's Farce. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966. OCLC 355476.