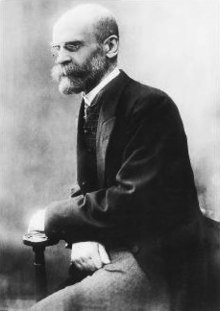

Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim (April 15, 1858 – November 15, 1917) was a French sociologist. He is known for his contributions to sociology and anthropology. He is considered as one of the founding fathers of sociology. He believed that the study of sociology should be scientific in nature.

Émile Durkheim | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | David Émile Durkheim 15 April 1858 |

| Died | 15 November 1917 (aged 59) |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure |

| Known for | Sacred–profane dichotomy Collective consciousness Social fact Social integration Anomie Collective effervescence |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Philosophy, sociology, education, anthropology, religious studies |

| Institutions | University of Paris, University of Bordeaux |

| Influences | Immanuel Kant, René Descartes, Plato, Herbert Spencer, Aristotle, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Auguste Comte. William James, John Dewey, Fustel de Coulanges, Jean-Marie Guyau, Charles Bernard Renouvier, John Stuart Mill |

| Influenced | Marcel Mauss, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Talcott Parsons, Maurice Halbwachs, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, Bronisław Malinowski, Fernand Braudel, Pierre Bourdieu, Charles Taylor, Henri Bergson, Emmanuel Levinas, Steven Lukes, Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Mary Douglas, Paul Fauconnet, Robert N. Bellah, Ziya Gökalp, David Bloor, Randall Collins, Neil Smelser[1] |

Personal Life

changeDurkheim was born into an orthodox Jewish family in the eastern French province of Lorraine, which at the time was disputed territory between France and Germany. He studied at École Normale Supérieure, where his class was considered to have produced some of the most prolific French intellectuals of his time. It was around this time that Durkheim began to develop an interest in studying societies from a scientific perspective. Since he was unable to study social sciences in France, he travelled to Germany in order to continue his sociological pursuits. Following the publication of several articles based on his studies in Germany, Durkheim was appointed to teach the first social science course at the University of Bordeaux in 1887. Throughout the next two decades, he would go on to publish a number of influential works in the field of sociology. Durkheim was eventually given the position of professor and chair of education and sociology at the University of Paris in 1906.

In 1898, Durkheim established L'Année Sociologique, a peer-reviewed academic journal. Many notable sociologists, such as Marcel Mauss, Henri Hubert, and Célestin Bouglé, were early contributors to the journal.

Durkheim married Louise Dreyfus in 1887, with whom he had two children. Durkheim died of a stroke in Paris on November 15, 1917, at the age of 59, two years after the death of his son during World War I.

Influences

changeDurkheim drew significant inspiration from the work of Auguste Comte, a French philosopher and mathematician considered to be one of the earliest contributors to sociological thought. Comte’s theory of positivism asserted that the sciences could be classified in order of complexity, with sociology being both the most recent and most complicated. Comte believed that the philosophy and history of a science were inseparable, and one must understand both in order to fully know a science.[2] Durkheim latched on to Comte’s idea that the scientific method could be applied to social sciences with an emphasis on assessing the facts. This can be seen in his approach to studying society, in which he places great emphasis on what he deems “social facts” and attempts to explain sociological phenomena through a more scientific lens.

Scholars have argued over the extent to which Durkheim’s Jewish heritage influenced his sociological theories. Despite eventually leading a secular life himself, he still grew up experiencing the antisemitism of the French. Though not focused on Judaism specifically, much of Durkheim's later work explored the role of religion in keeping people unified and societies functioning.

Notable Works & Theories

changeDurkheim believed that society is built upon shared rules and values. These rules are upheld by institutions like schools, families, and governments and help to keep society functioning smoothly. They are not just about practical things like education or law enforcement; they also help to shape our morals and beliefs.[3]

Society and the Individual

changeMuch of Durkheim's work was rooted in the intertwined nature of society and the individual. According to Durkheim, society and the individual are two halves of an inseparable whole.[4] Unlike previous scholars such as Herbert Spencer, who saw society as being based in self-interest and contractual relationships, Durkheim argued that the moral obligations and feelings of social belonging evoked within an individual are what keep societies functioning smoothly. The stronger the feelings of solidarity individuals feel toward their society, the stronger the society is as a whole. These societal bonds can be strengthened through shared beliefs or morals, such as those tied to traditions or religion. Individuals often adapt these concepts to suit their own personal interpretations and livelihoods while still adhering to the same unifying belief system.

The Profane and the Sacred

changeDurkheim often thought in dualities, particularly in regard to the profane and the sacred. When it comes to the individual, the soul is considered sacred whereas the body is considered profane. Society can similarly be split between these two categories, with the profane consisting of the secular aspects of existences such as labor and the sacred consisting of religion and other more prestigious ideals. This dichotomy is present in several of Durkheim's theories.[4]

Social Facts

changeSocial facts are phenomena present across societies which place an external constraint upon the individuals within said societies. These include laws, customs, morals, and other demographics and institutions. Individuals within a society tend to operate in obligation to these coercive factors, either for the good of the society as a whole or to protect their own sense of belonging within the society.[4]

Mechanical vs. Organic Solidarity

changeDurkheim suggested that the feelings of unity and solidarity fostered by society took on two distinct forms: mechanical and organic. Mechanical solidarity is when common values or ideals unite individuals within a society. Whereas mechanical solidarity emphasizes similarities and shared beliefs between individuals, organic solidarity highlights their differences. In organic solidarity, the unique roles that individuals play within a society work in tandem with one another and allow them to function as a collective whole.[5] Both of these modes of solidarity ultimately result in social integration.

Suicide

changeDurkheim is famous for his work on suicide. In this case study, he analyzed the causes of suicide from the perspective of society.[6] His theory has two core principles:

- That the way people are connected to each other in a group can affect how likely they are to commit suicide;[6] and

- That suicide is related to how much a person feels like they belong to their community (social integration) and how much they follow the rules and beliefs of their society (moral integration).[6]

Durkheim was not interested on the individual aspect of suicide, instead, he viewed suicide as a result of a "collective breakdown of society". Moreover, he viewed it as a symptom of the larger issues in society.[6] Durkheim argued that the rise in suicide rates was directly related to society’s departure from traditional or religious values as it moved toward more modern structures. The lack of a common mindset or obligations toward others led to a decline in an individual’s sense of belonging within a society.

Key Publications

change- The Division of Labour in Society (1893)

- The Rules of Sociological Method (1895)

- Suicide (1897)

- The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)

Impact

changeDurkheim is considered one of the founders of the modern understanding of social science and thus has had considerable influence within the field. He is responsible for introducing social sciences to the French school curriculum. Many of his students went on to adapt his ideas into their own sociological theories.

Durkheim’s nephew, sociologist and anthropologist Marcel Mauss, was one of his students who drew influence from his work. The two collaborated on Primitive Classifications in 1903, an essay published in L'Année Sociologique which responded to categorizations presented by idealist Immanuel Kant. Durkheim and Mauss argued that categories of human thought are strongly influenced by the societies from which they originate rather than by individuals.[7]

The sociological theories proposed by Durkheim received their fair share of criticism. His ideas clashed with those of Karl Marx, who placed heavy emphasis on the role of disparities between classes as a source of societal conflict. Other critics have accused Durkheim of oversimplifying human behavior and failing to acknowledge the complexity of social and religious experiences within different societies.[8]

References

change- ↑ Alexander, Jeffrey C.; Marx, Gary T.; Williams, Christine L. (2004). "Trust as an Aspect of Social Structure". In Alexander, Jeffrey C.; Marx, Gary T.; Williams, Christine L. (eds.). Self, Social Structure, and Beliefs: Explorations in Sociology. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-520-24137-4.

- ↑ Bourdeau, Michel (2023), Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.), "Auguste Comte", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2024-12-19

- ↑ Neuhouser, Frederick, ed. (2022), "Durkheim: Solidarity, Moral Facts, and Social Pathology", Diagnosing Social Pathology: Rousseau, Hegel, Marx, and Durkheim, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 192–228, ISBN 978-1-009-23503-7, retrieved 2024-10-24

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Durkheim, Emile (2005). "The Dualism of Human Nature and its Social Conditions". Durkheimian Studies / Études Durkheimiennes. 11: 35–45. ISSN 1362-024X.

- ↑ Perrin, Robert G. (1995). "Émile Durkheim's "Division of Labor" and the Shadow of Herbert Spencer". The Sociological Quarterly. 36 (4): 791–808. ISSN 0038-0253.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Mueller, Anna S.; Abrutyn, Seth; Pescosolido, Bernice; Diefendorf, Sarah (2021-03-31). "The Social Roots of Suicide: Theorizing How the External Social World Matters to Suicide and Suicide Prevention". Frontiers in Psychology. 12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.621569. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 8044307. PMID 33868089.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ Coser, Lewis A. (1988). "Primitive Classification Revisited". Sociological Theory. 6 (1): 85–90. doi:10.2307/201915. ISSN 0735-2751.

- ↑ Uricoechea, Fernando (1992). "Durkheim's Conception of the Religious Life : a Critique / Pour une critique de la conception durkheimienne de la vie religieuse". Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions. 79 (1): 155–166. doi:10.3406/assr.1992.1553.