Abu Sulayman Banakati

Abu Sulayman Banakati (Persian: ابوسلیمان بناکتی; died 1330), was a historian and poet, who lived during the late Ilkhanate era (time period). He is mainly known for his Persian world history book, the Rawdat uli al-albab fi maʿrifat al-tawarikh wa al-ansab, better known as Tarikh-i Banakati.

Abu Sulayman Banakati | |

|---|---|

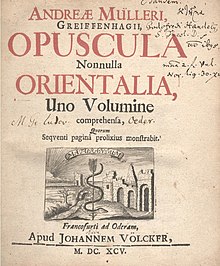

Manuscript of the Opuscula nonnulla orientalia, written in Latin by the German sinologist Andreas Müller. Banakati's Tarikh-i Banakati is included in the work. | |

| Died | 1330 |

| Occupation | Historian, poet |

| Language | Persian |

| Relatives | Taj al-Din Abu al-Fadl Banakati (father) Nizam al-Din Ali Banakati (brother) |

Banakati was also associated with the court of the Ilkhanate. He himself reported that he served as the chief poet at the court of the Ilkhanid ruler Ghazan (r. 1295–1304 ) in 1302.

Biography

changeOf Persian ancestry, Banakati was born in Banakat (later known as Shahrukhiya), a town in Transoxiana. His laqab (honorific name) was Fakhr al-Din Banakati. Belonging to a family of scholars, he was the son of the religious scholar Taj al-Din Abu al-Fadl Banakati, who is notable for writing a commentary on the masabih al-Sunnah by al-Baghawi (died 1122), known as the Kitab al-maysur. Banakati had a brother named Nizam al-Din Ali Banakati, who was a well known Sufi. Banakati was an educated scholar and skilled poet; according to his own reports, he served as the chief poet at the court of the Ilkhanid ruler Ghazan (r. 1295–1304 ) in 1302.[1] During the summer of that year, Banakati was given the title of malik al-shuʿara (King of Poets) by Ghazan.[2] Banakati reported that he became chief poet due to his brother being the previous holder of the office.[3] Al-Baghdadi credited Banakati with the writing of a diwan (collection of poems).[1] A sample of Banakati's poetry is mentioned in the Tadhkirat al-shu'ara ("Memorial of poets"), a biographical dictionary written by Dawlatshah Samarqandi (died 1495/1507).[4][1] Banakati died in 1330.[1]

Works

changeBanakati is mainly known for his world history book, the Rawdat uli al-albab fi maʿrifat al-tawarikh wa al-ansab, better known as Tarikh-i Banakati. The work was completed on 31 December 1317, and is divided into nine parts: (1) the prophets and patriarchs; (2) the monarchs of ancient Iran; (3) the prophet Muhammad and the caliphate; (4) Iranian dynasties that existed in the same period as the Abbasid Caliphate; (5) the Jews; (6) the Christians and the Franks; (7) the Indians; (8) the Chinese; and (9) the Mongols. The book ends with the start of the reign of the last Ilkhanid ruler, Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan (r. 1316–1335 ).[1][5] The last portion of part nine, which covers information from 1304 to 1317, is thought to be the first source on the reign of Öljaitü (r. 1304–1316 ).[1]

Banakati stated that most of the work is a shortened version of the world history book Jami' al-tawarikh by Rashid al-Din Hamadani (died 1318). As reported by some scholars, Banakati was able to add important information to his work due to his well known position at the Mongol court. Regardless of the shortness of the book, it is considered both unbiased and valuable, as well as one of the most reliable sources of its time. The Tarikh-i Banakati was first published in 1678, when its eighth part ("The History of the Chinese") was translated into Latin as Abdallae Beidavaei historia Sinensis by the German sinologist Andreas Müller, who mistook it as a work by the Persian scholar Qadi Baydawi (died 1319), probably due to a copyist including it as another work by Baydawi. The Latin translation of the book was later translated into English by Stephen Weston and released in London in 1820. The French writer Quatremère de Quincy (died 1849) included the work in his book, the Histoire des Mongols de la Perse.[1] Dawlatshah claimed that no other historian has written as much about China, India, the Jews and the Byzantines as Banakati has.[1]

By including some of his own words, Banakati noticeably portrayed Ghazan as a more pious figure, which testifies to the amalgamation of Mongol and Islamic ideas that was taking place at the time.[6] Similar to other poets, Banakati utilized both Iranian and Central Asian notions and titles of kingship. He referred to the Mongol ruler as Pādshāh, the Khusrav, and the Ṣāḥib-Qirān, but also as Khaqan (Qa’an) and Khan of Khans.[7]

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Ahmadi & Negahban 2013.

- ↑ Kamola 2019, p. 75.

- ↑ Brack 2016, p. 171.

- ↑ Melvin-Koushki 2017.

- ↑ Jackson 1988.

- ↑ Kamola 2019, p. 142.

- ↑ Brack 2016, p. 173.

Sources

change- Brack, Jonathan Z. (2016). Mediating Sacred Kingship: Conversion and Sovereignty in Mongol Iran (PDF) (PhD). University of Michigan.

- Kamola, Stefan (2019). Making Mongol History Rashid al-Din and the Jamiʿ al-Tawarikh. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1474421423.