Alternative splicing

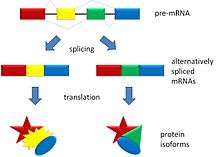

Alternative splicing allows DNA to code for more than one protein. It varies the exon make-up of the messenger RNA.

In alternative splicing the exons of the pre-messenger RNA produced by transcription are reconnected in different ways during RNA splicing.

This produces different mature messenger RNAs from the same gene. They get translated into different proteins. Thus, a single gene may code for multiple proteins.[1]

Alternative splicing is normal in eukaryotes. It greatly increases the diversity of proteins that can be encoded by the genome.[1] In humans, ~95% of multiexonic genes are alternatively spliced.[2][3][4]

There are various kinds of alternative splicing: the most common is exon skipping. An exon may be included in mRNAs under some conditions or in particular tissues, and omitted from the mRNA in others.[1] There are splicing activators that promote the use of a particular splice site, and splicing repressors that reduce the use of a particular site. New types of alternative splicing are being found.[4][5]

Abnormal variations in splicing occur in disease. Many human genetic disorders come from splicing variants.[4] Abnormal splicing variants may also contribute to the development of cancer.[6][7][8] High-throughput sequencing of RNA can for example be used to measure the genome-scale amount of deviating alternative splicing, such as in a cohort of colorectal cancers, where high amount of aberrant splicing was associated to poor patient survival.[9] Non-working splicing products are usually dealt with by post-transcriptional quality control.[10] That is, they are chopped up by enzymes.

Source of diversity

changeAlternative splicing (the re-combination of different exons) is a major source of genetic diversity in eukaryotes. One particular Drosophila gene (DSCAM) can be alternatively spliced into 38,000 different mRNA.[11]

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Black, Douglas L. (2003). "Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing". Annual Reviews of Biochemistry. 72 (1): 291–336. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. PMID 12626338. S2CID 23576288.

- ↑ multiexonic: those genes where the coding sections (exons) are separated by non-coding sections (introns)

- ↑ Pan, Q; et al. (2008). "Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing". Nature Genetics. 40 (12): 1413–1415. doi:10.1038/ng.259. PMID 18978789. S2CID 9228930.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Matlin, Arianne J.; Clark, Francis; Smith, Christopher W. J. (2005). "Understanding alternative splicing: towards a cellular code". Nature Reviews. 6 (5): 386–398. doi:10.1038/nrm1645. PMID 15956978. S2CID 14883495.

- ↑ David, C.J.; Manley, J.L. (2008). "The search for alternative splicing regulators: new approaches offer a path to a splicing code". Genes & Development. 22 (3): 279–285. doi:10.1101/gad.1643108. PMC 2731647. PMID 18245441.

- ↑ Skotheim R.I. and Nees M (2007). "Alternative splicing in cancer: noise, functional, or systematic?". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 39 (7–8): 1432–49. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2007.02.016. PMID 17416541.

- ↑ Bauer, Joseph Alan; et al. (2009). "A global view of cancer-specific transcript variants by subtractive transcriptome-wide analysis". PLOS ONE. 4 (3): e4732. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004732. PMC 2648985. PMID 19266097.

- ↑ Fackenthal J; Godley L (2008). "Aberrant RNA splicing and its functional consequences in cancer cells" (Free full text). Disease Models & Mechanisms. 1 (1): 37–42. doi:10.1242/dmm.000331. PMC 2561970. PMID 19048051.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Strømme JM, Johannessen B, Skotheim RI (2023). "Deviating alternative splicing as a molecular subtype of microsatellite stable colorectal cancer". JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics. 7 (7): e2200159. doi:10.1200/CCI.22.00159. PMID 36821799.

- ↑ Danckwardt S; et al. (2002). "Abnormally spliced beta-globin mRNAs: a single point mutation generates transcripts sensitive and insensitive to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay". Blood. 99 (5): 1811–6. doi:10.1182/blood.V99.5.1811. PMID 11861299.

- ↑ Schmucker D.; et al. (2000). "Drosophila Dscam is an axon guidance receptor exhibiting extraordinary molecular diversity". Cell. 101 (6): 671–684. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80878-8. PMID 10892653. S2CID 13829976.