DiGeorge syndrome

DiGeorge syndrome, or 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, is a syndrome caused by the deletion of a small segment of chromosome 22.[7] The symptoms are caused by the lack of those genes.

| DiGeorge syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | DiGeorge anomaly,[1][2] velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS),[3] Shprintzen syndrome,[4] conotruncal anomaly face syndrome (CTAF),[5] Takao syndrome,[6] Sedlackova syndrome,[7] Cayler cardiofacial syndrome,[7] CATCH22,[7] 22q11.2 deletion syndrome[7] |

| |

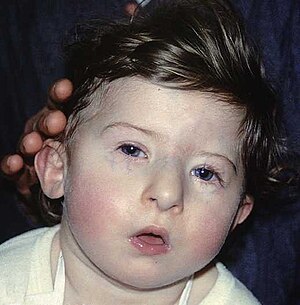

| A child with DiGeorge syndrome | |

| Medical specialty | Medical genetics |

| Symptoms | Variable; commonly congenital heart problems, specific facial features, cleft palate[7] |

| Complications | Kidney problems, hearing loss, autoimmune disorders[7] |

| Causes | Genetic (typically new mutation)[7] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and genetic testing[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, Alagille syndrome, VACTERL, Oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum[5] |

| Treatment | Involves many healthcare specialties[5] |

| Prognosis | Depends on the specific symptoms[3] |

| Frequency | 1 in 4,000[7] |

The symptoms often include congenital heart problems, facial features, infections, developmental delay, learning problems and cleft palate.[7] Other conditions include kidney problems, hearing loss and autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis or Graves disease.[7]

DiGeorge syndrome is due to the deletion of 30 to 40 genes in the middle of chromosome 22 at a location known as 22q11.2.[3] About 90% of cases occur due to a new mutation during early development, while 10% are inherited from a person's parents.[7]

The condition is autosomal dominant: only one affected chromosome is needed for the condition to occur.[7] Diagnosis is suspected based on the symptoms and confirmed by genetic testing.[5]

Although there is no cure, treatment can improve symptoms.[3] This often includes efforts to improve the function of the many organ systems involved.[8] Long-term outcomes depend on the symptoms present and the severity of the heart and immune system problems.[3] With treatment, life expectancy may be normal.[9]

DiGeorge syndrome occurs in about 1 in 4,000 people.[7] The syndrome was first described in 1968 by American physician Angelo DiGeorge.[10][11] In late 1981, the underlying genetics were determined.[11]

References

change- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "22q11.2 deletion syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ Shprintzen, RJ; Goldberg, RB; Lewin, ML; Sidoti, EJ; Berkman, MD; Argamaso, RV; Young, D (January 1978). "A new syndrome involving cleft palate, cardiac anomalies, typical facies, and learning disabilities: velo-cardio-facial syndrome". The Cleft Palate Journal. 15 (1): 56–62. PMID 272242.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Chromosome 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2017. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Burn, J; Takao, A; Wilson, D; Cross, I; Momma, K; Wadey, R; Scambler, P; Goodship, J (October 1993). "Conotruncal anomaly face syndrome is associated with a deletion within chromosome 22q11". Journal of Medical Genetics. 30 (10): 822–4. doi:10.1136/jmg.30.10.822. PMC 1016562. PMID 8230157.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 "22q11.2 deletion syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. July 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ Kobrynski LJ, Sullivan KE (October 2007). "Velocardiofacial syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome: the chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndromes". Lancet. 370 (9596): 1443–52. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61601-8. PMID 17950858. S2CID 32595060.

- ↑ Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (2015). Goldman-Cecil Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 702. ISBN 9780323322850. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- ↑ DiGeorge, A (1968). "Congenital absence of the thymus and its immunologic consequences: concurrence with congenital hypoparathyroidism". March of Dimes-Birth Defects Foundation: 116–21.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Restivo, Angelo; Sarkozy, Anna; Digilio, Maria Cristina; Dallapiccola, Bruno; Marino, Bruno (February 2006). "22q11 Deletion syndrome: a review of some developmental biology aspects of the cardiovascular system". Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. 7 (2): 77–85. doi:10.2459/01.JCM.0000203848.90267.3e. PMID 16645366. S2CID 25905258.

- McDonald-McGinn DM, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH (2005). "22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome". In Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K (eds.). GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301696. NBK1523.

- Firth HV (2009). "22q11.2 Duplication". In Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K (eds.). GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301749. NBK3823.

Other websites

change| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |