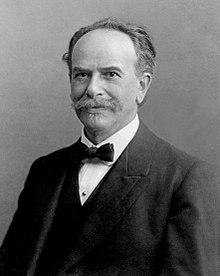

Franz Boas

Franz Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-born American anthropologist. He is considered by many to have been the 'Father of American Anthropology.'[1] While today archaeology, cultural anthropology, linguistics, and Biological anthropology are often considered somewhat separate areas of study in anthropology, Boas used each of these fields to address research questions.[2]

Early life

changeBoas was born in Prussia, or modern-day Germany, to wealthy, well-educated Jewish parents. In an effort to expose him to the values of the Enlightenment, Boas's parents enrolled in a very strong early education. During his primary school years, Boas explored the field of natural history, and as he moved on to secondary school he conducted research on the natural range of plants.[3]

Academic Career

changeFranz Boas attended Heidelberg University for one semester, before transferring to Bonn University where he studied mathematics, physics, and geography.[3] He received a doctorate in physics in 1881 from the University of Kiel. Today, Boas' doctorate would be closer to a degree in geography than physics.[4]

Boas continued to study geography and eventually did fieldwork in Baffin Island, Canada with the native Inuit there. He first travelled to Baffin Island in 1883 to study the role of the environment in Inuit migrations.[2][5] He published his findings in 1888 in The Central Eskimo[5]

Boas returned to Germany for a time, but due to rising antisemitism, he decided to move to the United States.[1] He worked as an editor for Science and as a teacher of anthropology at Clark University. He left the university in 1892 and shortly after went north to collect field-based material for the 1893 World's Colombian Exposition. After the exposition, the material was given to the Field Museum in Chicago, where Boas became the curator of anthropology. During this time Boas became involved in the Fin de Siècle debates.[2] It was here he argued that anthropology should be different from the natural sciences and how they apply universal laws. He also began the groundwork that would grow into historical particularism: the idea that every aspect of a culture has a unique and relevant history.

Boas eventually settled at the University of Columbia in 1896. There, he created the first PhD program for anthropology in the United States.[3] At Columbia, he taught some of his most famous students, including Alfred Kroeber, Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, Edward Sapir, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Later life

changeFranz Boas was censored by the American Anthropological Association (AAA) in December 1919 for a publication he wrote denouncing anthropologists who became involved with the war effort during the First World War. This persisted for the remainder of his life, not being reversed until 2005.[6] He was very critical of Nazism as well as critical of the radical the war effort in the United States. Boas was also involved with combating racism.[7] In 1963 Thomas Gossett claimed that "It is possible that Boas did more to combat race prejudice than any other person in history." Franz Boas died of a stroke on December 21, 1942.[7] According to legend he died in the arms of none other than Claude Levi-Strauss.

Contributions to Anthropology

changeFranz Boas is often credited with the development of 'historical particularism[8]', as well as 'cultural relativism.[9]' Boas was a founding member of the American Anthropology Association (AAA) and served as one of the organization's first vice presidents.

Franz Boas is often credited with the development of several concepts in anthropology including 'historical particularism[8]', 'cultural relativism[9]', and ‘cultural determinism’. He argued culture played a significant role in human behavior and that cultures should be studied on their own terms, considering the specific and unique histories at hand.[10] In general, the school of thought associated with Franz Boas, often referred to as "Boasian anthropology," emphasized the importance of multi-approach, context-based methods to understanding human societies. His theories laid the foundation for modern cultural anthropology.

Although Boas was commonly known as the “Father of Anthropology” it is also important to recognize that other anthropologists like George Hunt,[11] Zora Neale Hurston,[12] Ella Deloria,[13] Francis La Flesche,[14] and Anténor Firmin[15] either worked with him, did similar work before him, or worked under his guidance and are not equally given the credit of this title.

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Salmon, Gildas (2013). Franz Boas. Armand Colin. p. 191. doi:10.3917/arco.kali.2013.01.0191. ISBN 978-2-200-28547-0.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Boas, Franz (1989). A Franz Boas reader : the shaping of American anthropology, 1883-1911. Stocking, George W., Jr. (George Ward), 1928-2013. (Midway reprint ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-06243-0. OCLC 20806496.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Mair, Lucy; Harris, Marvin (March 1969). "The Rise of Anthropological Theory: A History of Theories of Culture". Man. 4 (1): 144. doi:10.2307/2799288. ISSN 0025-1496. JSTOR 2799288.

- ↑ Koelsch, William A. (2004). "Franz Boas, geographer, and the problem of disciplinary identity". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 40 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1002/jhbs.10181. ISSN 0022-5061. PMID 14724914.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Boas, Franz. (2016). Central Eskimo. Read Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4733-7817-9. OCLC 953849457.

- ↑ "American Anthropological Association". www.americananthro.org. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 FLEURE, H. J. (January 1943). "Prof. Franz Boas". Nature. 151 (3820): 75–76. Bibcode:1943Natur.151...75F. doi:10.1038/151075a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4065533.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Historical Particularism: Definition & Examples". Study.com. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Cultural Relativism". www.cultural-relativism.com. Archived from the original on 2020-05-29. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ↑ Boas, F. (1896). The Limitations of the Comparative Method of Anthropology. Science, 4(103), 901–908. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1623004

- ↑ Cannizzo, J. (1983). George Hunt and the Invention of Kwakiutl Culture. The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 20(1), 44–58.

- ↑ Hurston, Z. N. (2018). Barracoon : the story of the last “black cargo” (D. G. Plant, Ed.; First edition.). Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

- ↑ Prater, J. (1995). Ella Deloria: Varied Intercourse: Ella Deloria’s Life and Work. Wicazo Sa Review, 11(2), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/1409095

- ↑ Mark, J. (1982). Francis La Flesche: The American Indian as Anthropologist. Isis, 73(4), 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/353113

- ↑ Fluehr-Lobban, C. (2000). Anténor Firmin: Haitian Pioneer of Anthropology. American Anthropologist, 102(3), 449–466. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2000.102.3.449