Chinese characters

Chinese characters are symbols used to write the Chinese and Japanese languages. In the past, other languages like Korean and Vietnamese also used them. The beginning of these characters was at least 3000 years ago, making them one of the oldest writing systems in the world that is still used today. In Chinese they are called hanzi (汉字/漢字), which means "Han character". In Japanese they are called kanji, hanja in Korean, and chữ Hán in Vietnamese.

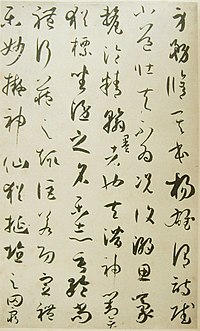

Chinese characters are an important part of East Asian culture. The art of writing Chinese characters is called calligraphy.

Writing

changeChinese characters are a type of logogram, which are written symbols that represent words instead of sounds. Most earlier Chinese characters were pictographs, which are simple pictures used to mean some kind of thing or idea. Today, very few modern Chinese characters are pure pictographs, but are a combination of two or more simple characters, also known as radicals. While many radicals and characters show a word's meaning, some give hints of the word's pronunciation instead.

To better explain the different purposes and types of Chinese characters that exist, Chinese scholars have divided Chinese characters into six categories known as liushu (六书 / 六書), literally translated as the Six Books. The six types of Chinese characters are:

- Pictographs, xiàng xÍng (象形): characters that use a simple picture, or one radical, that directly represent concrete nouns, like persons, places, and things. Examples include:

| Chinese

character (traditional/ simplified) |

Pīnyīn

(Mandarin pronunciation) |

Meaning | Looks like |

|---|---|---|---|

| 山 | shān | mountain | 3 peaks |

| 人 | rén | person/people/humanity | a creature standing on 2 legs |

| 口 | kŏu | mouth | an open mouth |

| 刀 | dāo | sword/knife | a blade |

| 木 | mù | wood | a tree |

| 日 | rì | sun/day | the sun with a cloud in the middle |

| 月 | yuè | moon/month | the moon in the shape of a crescent |

| 女 | nǚ | woman/girl/female | person with large breasts |

| 子 | zi/zĭ | child | a child wrapped in a blanket |

| 馬 / 马 | mǎ | horse | a horse with a head, a mane, a body, a tail, and 4 legs |

| 鳥 / 鸟 | niǎo | bird | a creature with a head and a wing with feathers |

| 目 | mù | eye | an eye with 2 eyelids |

| 水 | shuǐ | water | three streams of water |

- Simple ideograms, zhǐ shì (指事): characters that use one radical, to represent abstract nouns, such as ideas and abstractions. Examples include:

| Chinese

character (traditional/ simplified) |

Pīnyīn

(Mandarin pronunciation) |

Meaning | Looks like |

|---|---|---|---|

| 一 | yī | one | 1 line |

| 二 | èr | two | 2 lines |

| 三 | sān | three | 3 lines |

| 大 | dà | big/large/great | a person 人 holding out his/her arms as wide as possible |

| 天 | tiān | heaven/sky/day | like 大, but one line above, so the greatest of the great |

| 小 | xiǎo | little/small | fingers holding onto a needle |

| 上 | shàng | up/above/previous | a plant's stem and leaf above the ground |

| 下 | xià | down/below/next | a plant's roots |

| 本 | běn | root | a tree 木 with its roots showing underground |

| 末 | mò | apex | a tree 木 with one extra line on the top, so the very top |

- Complex ideograms, huì yì (会意), or characters that use more than one radical to represent more complex ideas or abstractions. Examples include:

| Chinese

character (traditional/ simplified) |

Pīnyīn

(Mandarin pronunciation) |

Meaning | Looks like |

|---|---|---|---|

| 明 | míng | bright/light/tomorrow | a sun 日 and a moon 月 next to each other, indicating that tomorrow happens after the sun and moon passes |

| 好 | hǎo | good | a woman 女 and a child 子 next to each other, indicating that a woman with a child is good |

| 休 | xiū | rest | a person 亻(人) next to a tree 木 |

| 林 | lín | woods | two trees 木 next to each other |

| 森 | sēn | forest | three trees 木 next to each other |

- Phonetic loan characters, jiǎ jiè (假借), or characters that borrow a radical from other characters because they sound similar, not because they have the same meaning. These are called rebuses, or pictures/letters/numbers/symbols that are used to represent a word with the same pronunciation. For example, someone writes the sentence, "I'll see you tonight" as "⊙ L C U 2nite". Sometimes, a new character is made for the original word to not have any confusion between the different words.

| Chinese

character (traditional/ simplified) |

Rebus word

(Mandarin pronunciation) |

Original word | New character for the original word |

|---|---|---|---|

| 來/来 | lái "to come" | lai "wheat" | 麥/麦 mài |

| 四 | sì "four" | sī "nostril(s)" | 泗, can also mean "mucus/sniffle" |

| 北 | běi "north" | bèi "back (of the body)" | 背 |

| 要 | yào "to want" | yāo "waist" | 腰 |

| 少 | shǎo "few/little" | shā "sand" | 沙 and 砂 |

| 永 | yŏng "forever/eternity" | yŏng "to swim" | 泳 |

Common examples of words using phonetic characters are the names of countries, such as Canada, which is pronounced Jiānádà (加拿大) in Chinese. While the third character 大 dà, which has the meaning "big/large/great", seems to describe Canada well, since it is a big country, the first two characters 加 jiā, meaning "to add", and 拿 ná, meaning "to take", have no obvious relation to Canada. Therefore, it is safe to say that these characters were chosen only because the pronunciation of each character sounds similar to the syllables of the English name of the country.

- Semantic-phonetic compounds, xíng shēng (形声), are characters where at least one radical hints at the word's meaning and at least one radical hints at the word's pronunciation. Most Chinese characters are these kinds of characters. For example, the character 媽 / 妈 mā means mother, and the character is made of 2 radicals, 女 and 馬 / 马. The semantic radical 女 means female/woman/girl, since the word's meaning is related to the radical, and even though the meaning of the phonetic radical 馬 / 马 mǎ has little to do with the word's meaning, if any at all, it sounds similar to the word 媽 / 妈 mā,so it is used to help the reader remember the word's pronunciation. Other examples include:

| Chinese

character (traditional/ simplified) |

Pīnyīn

(Mandarin pronunciation) |

Meaning | Semantic radical | Phonetic radical (meaning) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 清 | qīng | clear | 氵(水) water | 青 qīng (greenish-blue) |

| 睛 | jīng | eye | 目eye | 青 qīng (greenish-blue) |

| 菜 | cài | vegetable/food dish | 艹 (艸) grass/plant | 采 cǎi (harvest) |

| 沐 | mù | to wash oneself | 氵(水) water | 木 mù (wood) |

| 淋 | lín | to pour | 氵(水) water | 林 lín (woods) |

| 嗎 / 吗 | ma | yes-no question marker (word that ends the sentence of a yes-no question) | 口 mouth (interjections and particles often have this radical) | 馬/马 mǎ (horse) |

- Transformed cognates, zhuan zhu (转注), or characters that used to be different ways of writing other characters, but have later taken on a different meaning.

| Cognate word | Original word | New pronunciation and meaning of cognate word |

|---|---|---|

| 考 | 老 lăo "old" | kào “test, exam” |

Nobody knows exactly how many Chinese characters there are, but the biggest Chinese dictionaries list about fifty thousand characters,[1] even though most of them are only variants of other characters seen in very old texts. For example, the character 回 (huí) has also been written as the variant characters 迴,廻,囬,逥,廽,and 囘, although most Chinese people only know and use the variant 回. Studies in China show that normally three to four thousand characters are used in daily life, so it is safe to say that someone needs to know three to four thousand characters to be functionally literate in Chinese, or be able to read everyday writing without serious problems.

Characters are a kind of graphic language, much different from languages that use an alphabet such as English. The correct way to tell between them is to remember the structure and meaning of every character, not pronunciation, because there is a very close relationship between meaning and structure of characters. Example: 房(house)=户+方. 房 is a shape-pronunciation character. 户 is for shape and 方 is for pronunciation. 户 means 'door'. 房 means 'A person lives behind a door'. 方 pronunciation is fang and tone is 1, and with the tone mark it is written as fāng. 房 pronunciation is also fang, but tone is 2, with the tone mark it is written as fáng.

Chinese characters in other languages

changeChinese characters have been used to write other languages, particularly in Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese:

Japanese

changeIn Japanese, characters that are borrowed from the Chinese language are called kanji.[2] Kanji can be used to write both native Japanese words and Chinese loanwords. Japanese writing uses a mix of kanji and two kana systems.[3] Kanji is mostly used to show a word's meaning, while hiragana and katakana are syllabaries that show the pronunciation of Japanese words, all three of which are often used in combination when writing Japanese. Generally, the educational level of a Japanese person is indicated by the number of Chinese characters understood by this person.

Korean

changeIn Korean, they are called hanja.[4] Throughout most of Korean history, hanja was the only writing system most literate Koreans knew. Even though hangul was invented in 1446, it was only used by commoners and not by academics or the government until Korea gained independence from Japan. Nowadays, while Koreans nowadays mostly write in hangul, the native Korean alphabet, people have found that some meanings cannot be expressed clearly by just hangul, so people need to use Chinese characters as a note with a bracket.

In North Korea, people write almost completely in hangul since Kim Il-sung abolished hanja from Korean.[5] In South Korea, people mostly write in hangul, and they sometimes write hanja. Native Korean words are almost always written in hangul. Hanja are usually only used to write words that are borrowed from the Chinese language, and are usually only used when the word's meaning isn't obvious based on the context.

Vietnamese

changeIn Vietnamese, they are called chữ Nôm. Many Chinese loanwords were used in Vietnamese, especially in old Vietnamese literature.[6] While Vietnamese used many Chinese characters, they also invented tens of thousands of their own characters to write Vietnamese words. The radicals used in chữ Nôm were usually a mix of the words' meanings and pronunciations.

Related pages

change- Simplified Chinese characters

- Traditional Chinese characters

- Wade–Giles, a romanization system used to write Chinese using the Roman alphabet

References

change- ↑ "How many Chinese characters do you need to know?". Fluent in Mandarin.com. 2014-02-20. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ↑ Matsunaga, Sachiko (October 1996). "The Linguistic Nature of Kanji Reexamined: Do Kanji Represent Only Meanings?". The Journal of the Association of Teachers of Japanese. 30 (2): 1–22. doi:10.2307/489563. Archived from the original on 2022-12-02. Retrieved 2024-06-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Taylor, Insup; Taylor, M. Martin (1995). Writing and literacy in Chinese, Korean, and Japanese. Amsterdam ; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub. Co. p. 305. ISBN 90-272-1794-7.

- ↑ Coulmas, Florian (1991). The writing systems of the world. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-631-18028-9.

- ↑ Chan, Jackie Soy (2000). "Asia's Orthographic Dilemma, by William C. Hannas. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997. Pp. 338 ISBN 0-8248-1842-3". South Pacific Journal of Psychology. 12: 67–69. doi:10.1017/S0257543400000547.

- ↑ Handel, Zev (2019). Sinography: the borrowing and adaptation of the Chinese script. Leiden Boston: Brill. p. 125. ISBN 9789004386327.