Khoekhoe language

The Khoekhoe /ˈkɔɪkɔɪ/ language (Khoekhoegowab), or Nama (Namagowab) /ˈnɑːmə/, Damara (ǂNūkhoegowab),[3] Nama/Damara,[4][5] and Hottentot[b], is the most common of the non-Bantu languages of Southern Africa that make much use of click consonants. Because of that, Khoekhoe used to be Khoisan, but this group is not used now. It is part of the Khoe language family, and is used in Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa, usually by three ethnic groups: Namakhoen, ǂNūkhoen, and Haiǁomkhoen.

| Khoekhoe | |

|---|---|

| Nama/Damara | |

| Khoekhoegowab | |

| Native to | Namibia, Botswana and South Africa |

| Region | Orange River, Great Namaland, Damaraland |

| Ethnicity | Khoikhoi, Nama, Damara, Haiǁom, ǂKhomani |

Native speakers | 200,000 ± 10,000 (2011)[1] |

Khoe–Kwadi

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:naq – Khoekhoe, Namahgm – Haiǁom |

| Glottolog | nort3245 Subfamily: North Khoekhoenama1264 Language: Namahaio1238 Language: Haiǁom-Akhoe |

| ELP | Khoekhoe |

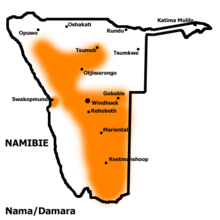

The distribution of the Nama language in Namibia | |

| The Khoe language | |

| person | Khoe-i |

| people | Khoekhoen |

| language | Khoekhoegowab |

History change

The Haiǁom, who before used a Juu language, moved to Khoekhoe. The name Khoekhoen, is from the word khoe "person", copied twice and the suffix -n to be the general plural. Georg Friedrich Wreede was the first European to look at the language, after going to ǁHui!gaeb (later Cape Town) in 1659.[source?]

Status change

Khoekhoe is a national language in Namibia. In Namibia and South Africa, state-owned broadcasting corporations make and give out radio programs in Khoekhoegowab.

It is thought that only about 167,000 users of Khoekhoegowab live in Africa, making it an endangered language. In 2019, the University of Cape Town did an amount of short courses (classes) teaching the language, and on 21 September 2020 started its new Khoi and San Centre. An undergraduate degree series of classes is being developed.[7]

Dialects change

Present-day scholars generally see three dialects:

- Nama–Damara, with Sesfontein Damara

- Haiǁom

- ǂĀkhoe, itself a dialect cluster, and middle between Haiǁom and the Kalahari Khoe languages

They are different enough that it possibly may be thought of as two or three different languages.[source?]

- Eini (extinct) is not far from it but is now counted as a distinct language.[source?]

Phonology change

Vowels change

Khoekhoe uses 5 vowel qualities, seen as oral (sounds produced with the help of the mouth) /i e a o u/ and nasal /ĩ ã ũ/. /u/ is strongly rounded, /o/ only softly. /a/ is the only vowel with a good amount of allophony; it is pronounced [ə] before /i/ or /u/.

Tone change

Nama is seen as having three[8] or four[9][10][11] tones, /á, ā, à/ or /a̋, á, à, ȁ/, that may take place on different mora (vowels and final nasal consonants). The high sound is higher when it takes place on one of the high vowels (/í ú/) or on a nasal (/ń ḿ/) than on mid or low vowels (/é á ó/).

The sounds combine, (move together) starting a small number of 'tone melodies' (word sounds), which have sandhi forms in certain syntactic places. The most important melodies, in the way that it is said and main sandhi forms, are as follows:

| Citation | Sandhi | Meaning | Melody |

|---|---|---|---|

| ǃ̃ˀȍm̀s | ǃ̃ˀòm̏s | butting, hitting s.t. | low |

| ǃ̃ˀȍḿs | an udder | low rising | |

| ǃ̃ˀòm̀s | forcing out of a burrow | mid | |

| ǃ̃ˀòm̋s | ǃ̃ˀòm̀s | a pollard | high rising |

| ǃ̃ˀóm̀s | ǃ̃ˀóm̏s | coagulating, prizing out [a thorn] | low falling |

| ǃ̃ˀőḿs | ǃ̃ˀóm̀s | a fist | high falling |

Stress change

Under a phrase (part of a sentence), lexical words receive greater stress than grammatical words. Using a word, the first syllable receives the most stress. Syllables afterwards get less and less stress and are spoken more and more quickly.

Consonants change

Nama has 31 consonants: 20 clicks and only 11 non-clicks.[12]

Non-clicks change

Orthography in brackets.

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ||

| Plosive | p ~ β ⟨b/p⟩ | t ~ ɾ ⟨t/d/r⟩ | k ⟨k/g⟩ | ʔ ⟨-⟩ |

| Affricate | t͜sʰ ⟨ts⟩ | k͜xʰ ⟨kh⟩ | ||

| Fricative | s ⟨s⟩ | x ⟨x⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ |

Between vowels, /p/ is said [β] and /t/ is said [ɾ]. The affricates strongly aspirate, and may be thought of phonemically as aspirated stops; in Korana they use [tʰ, kʰ].

Beach (1938)[13] said that the Khoekhoe of the time had a velar lateral ejective affricate, [kʟ̝̊ʼ], commonly seen in languages with clicks. This sound no longer occurs in Khoekhoe but remains in its cousin Korana.

Clicks change

The clicks are twice articulated consonants. Each click consists of one of four primary articulations or "influxes" and one of five secondary articulation or "effluxes". The mix results in 20 phonemes.[14]

| accompaniment | affricated clicks | 'sharp' clicks | standardised

orthography | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dental

clicks |

lateral

clicks |

alveolar

clicks |

palatal

clicks | ||

| Tenuis | ᵏǀ | ᵏǁ | ᵏǃ | ᵏǂ | ⟨ǃg⟩ |

| Aspirated | ᵏǀʰ | ᵏǁʰ | ᵏǃʰ | ᵏǂʰ | ⟨ǃkh⟩ |

| Nasal | ᵑǀ | ᵑǁ | ᵑǃ | ᵑǂ | ⟨ǃn⟩ |

| Voiceless aspirated nasal | ᵑ̊ǀʰ | ᵑ̊ǁʰ | ᵑ̊ǃʰ | ᵑ̊ǂʰ | ⟨ǃh⟩ |

| Glottalized nasal | ᵑ̊ǀˀ | ᵑ̊ǁˀ | ᵑ̊ǃˀ | ᵑ̊ǂˀ | ⟨ǃ⟩ |

The aspiration on the aspirated clicks is usually light but is 'raspier' than the aspirated nasal clicks, with a sound like the ch of Scottish loch. The glottalised clicks are clearly voiceless because of the hold before the release, and they are used as simple voiceless clicks in the traditional orthography. The nasal part is not able to be heard in initial position; the voiceless nasal component of the aspirated clicks is also hard to hear when not between vowels, so to foreign ears, it may sound like a longer but less raspy version of the contour clicks.

Tindall says that European learners usually pronounce the lateral clicks by placing the tongue against the side teeth and that this way is "harsh and foreign to the native ear". The Namaqua cover the whole of the palate with the tongue and produce the sound "as far back in the palate as possible".[15]

Phonotactics change

Lexical root words consist of two or rarely three moras, in the form CVCV(C), CVV(C), or CVN(C). (The initial consonant is required.) The middle consonant may only be w r m n (w is b~p and r is d~t), while the final consonant (C) may only be p, s, ts. Each mora has tone, but the second may only be high or medium, for six tone "melodies": HH, MH, LH, HM, MM, LM.

Oral vowel lines in CVV are /ii ee aa oo uu ai [əi] ae ao au [əu] oa oe ui/. Due to the reduced number of nasal vowels, nasal lines are /ĩĩ ãã ũũ ãĩ [ə̃ĩ] ãũ [ə̃ũ] õã ũĩ/. Lines ending in a high vowel (/ii uu ai au ui ĩĩ ũũ ãĩ ãũ ũĩ/) are said quicker than others (/ee aa oo ae ao oa oe ãã õã/), more like diphthongs and long vowels than like vowel sequences in hiatus. The tones are contours. CVCV words usually have the same vowel sequences, but there are many exceptions. The two tones are also more different.

Vowel-nasal sequences are stuck to non-front vowels: /am an om on um un/. Their tones are also contours.

Grammatical particles have the form CV or CN, with any vowel or tone, where C may be any consonant but a click, and the next letter cannot be NN. Suffixes and a third mora of a root, may have the form CV, CN, V, N, with any vowel or tone; there are also three C-only suffixes, -p 1m.sg, -ts 2m.sg, -s 2/3f.sg.

Orthography change

There have been a few orthographies used for Nama. A Khoekhoegowab dictionary (Haacke 2000) uses the modern standard.

In standard orthography, the consonants b d g are used for words with one of the lower tone melodies and p t k for one of the higher tone melodies. W is only used in the middle of vowels, but it may be replaced with b or p depending on melody. Overt tone marking is otherwise generally omitted.

| Orthography | Transcription | Melody | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| gao | /kȁó/ | low rising | 'rule' |

| kao | /kàő/ | high rising | 'be dumbfounded' |

| ǀhubu (or ǀhuwu) | /ǀʰȕwú/ | low rising | 'to stop hurting' |

| ǀhupu (or ǀhuwu) | /ǀʰùwű/ | high rising | 'to get out of breath' |

Nasal vowels are written with a circumflex. All nasal vowels are long, as in hû /hũ̀ṹ/ 'seven'. Long (double) vowels are written with a macron, as in ā /ʔàa̋/ 'to cry, weep'; these make two moras (two tone-bearing units).

A glottal stop is not written at the beginning of a word (where it is predictable), but it is written with a hyphen in compound words, such as gao-aob /kȁòʔòȁp/ 'chief'.

The clicks are written using the IPA symbols:

- ǀ (a vertical bar) for a dental click

- ǁ (a double vertical bar) for a lateral click

- ǃ (an exclamation mark) for an alveolar click

- ǂ (a double dagger) for a palatal click

Sometimes other characters are used, like the hash (#) in place of ǂ.[16]

Grammar change

Nama has a subject–object–verb word order, three noun classes (masculine/gu-class, feminine/di-class and neuter/n-class) and three grammatical numbers (singular, dual and plural). Pronominal enclitics are used to mark person, gender, and number on the noun phrases.

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feminine/Di-class | Piris | Pirira | Piridi | goat |

| Masculine/Gu-class | Arib | Arikha | Arigu | dog |

| Neutral/N-class | Khoe-i | Khoera | Khoen | people |

Person, gender and number markers change

The PGN (person-gender-number) markers are enclitic pronouns that get on to noun phrases.[17] The PGN markers make a difference between first, second, and third person, masculine, feminine, and neuter gender, and singular, dual, and plural number. The PGN markers can be cut into nominative, object, and oblique paradigms.

Nominative change

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Singular | ta | ts | b/mi/ni | ta | s | s | — | — | -i |

| Dual | khom | kho | kha | m | ro | ra | m | ro | ra |

| Plural | ge | go | gu | se | so | di | da | du | n |

Object change

(PGN + i)

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Singular | te | tsi | bi/mi/ni | te | si | si | — | — | -i |

| Dual | khom | kho | kha | mi/im | ro | ra | mi/im | ro | ra |

| Plural | ge | go | gu | se | so | di | da | du | ni/in |

Oblique change

(PGN + a)

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Singular | ta | tsa | ba/ma/na | ta | sa | sa | — | — | -e |

| Dual | khoma | kho | kha | ma | ro | ra | mo | ro | ra |

| Plural | ge | go | ga | se | so | de | da | do | na |

Articles change

Khoekhoe has four articles: ti, si, sa, ǁî. These articles can be combined with PGN markers.

Examples from Haacke (2013):

- si-khom "we two males" (someone other than addressee and I)

- sa-khom "we two males" (addressee and I)

- ǁî-khom "we two males" (someone else talked to previously and I)

| ti | si | sa | ǁî |

|---|---|---|---|

| +definite | +definite | +definite | +definite |

| +speaker | +speaker | +addressee | +discussed |

| +human | -addressee | +human | |

| +singular | +human | ||

| -singular |

Clause headings change

There are three clause markers, ge (declarative), kha (interrogative), and ko/km (assertive). These markers appear in matrix clauses, and appear after the subject.[18]

Sample text change

After this is a sample text in the Khoekhoe language.

- Nē ǀkharib ǃnâ da ge ǁGûn tsî ǀGaen tsî doan tsîn; tsî ǀNopodi tsî ǀKhenadi tsî ǀhuigu tsî ǀAmin tsîn; tsî ǀkharagagu ǀaon tsîna ra hō.

- In this region, we find springbuck, oryx, and duiker; francolin, guinea fowl, bustard, and ostrich; and also various kinds of snake.

Common words and phrases change

- ǃGâi tsēs – Good day

- ǃGâi ǁgoas – Good morning

- ǃGâi ǃoes – Good evening

- Matisa – How are you?

- ǃGâise ǃgû re – Goodbye

- ǁKhawa mûgus – See you soon

- Regkomtani – I'll manage

- Tae na Tae – How's it hanging (direct translation "What is what")

Bibliography change

- Khoekhoegowab/English for Children, Éditions du Cygne, 2013, ISBN 978-2-84924-309-1

- Beach, Douglas M. 1938. The Phonetics of the Hottentot Language. Cambridge: Heffer.

- Brugman, Johanna. 2009. Segments, Tones and Distribution in Khoekhoe Prosody. PhD Thesis, Cornell University.

- Haacke, Wilfrid. 1976. A Nama Grammar: The Noun-phrase. MA thesis. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- Haacke, Wilfrid H. G. 1977. "The So-called "Personal Pronoun" in Nama." In Traill, Anthony, ed., Khoisan Linguistic Studies 3, 43–62. Communications 6. Johannesburg: African Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Haacke, Wilfrid. 1978. Subject Deposition in Nama. MA thesis. Colchester, UK: University of Essex.

- Haacke, Wilfrid. 1992. "Compound Noun Phrases in Nama". In Gowlett, Derek F., ed., African Linguistic Contributions (Festschrift Ernst Westphal), 189–194. Pretoria: Via Afrika.

- Haacke, Wilfrid. 1992. "Dislocated Noun Phrases in Khoekhoe (Nama/Damara): Further Evidence for the Sentential Hypothesis". Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere, 29, 149–162.

- Haacke, Wilfrid. 1995. "Instances of Incorporation and Compounding in Khoekhoegowab (Nama/Damara)". In Anthony Traill, Rainer Vossen and Marguerite Anne Megan Biesele, eds., The Complete Linguist: Papers in Memory of Patrick J. Dickens", 339–361. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Haacke, Wilfrid; Eiseb, Eliphas and Namaseb, Levi. 1997. "Internal and External Relations of Khoekhoe Dialects: A Preliminary Survey". In Wilfrid Haacke & Edward D. Elderkin, eds., Namibian Languages: Reports and Papers, 125–209. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag for the University of Namibia.

- Haacke, Wilfrid. 1999. The Tonology of Khoekhoe (Nama/Damara). Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung/Research in Khoisan Studies, Bd 16. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Haacke, Wilfrid H.G. & Eiseb, Eliphas. 2002. A Khoekhoegowab Dictionary with an English-Khoekhoegowab Index. Windhoek : Gamsberg Macmillan. ISBN 99916-0-401-4

- Hagman, Roy S. 1977. Nama Hottentot Grammar. Language Science Monographs, v 15. Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Krönlein, Johann Georg. 1889. Wortschatz der Khoi-Khoin (Namaqua-Hottentotten). Berlin : Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft.

- Olpp, Johannes. 1977. Nama-grammatika. Windhoek : Inboorlingtaalburo van die Departement van Bantoe-onderwys.

- Rust, Friedrich. 1965. Praktische Namagrammatik. Cape Town : Balkema.

- Vossen, Rainer. 2013. The Khoesan Languages. Oxon: Routledge.

References change

- ↑ Brenzinger, Matthias (2011) "The twelve modern Khoisan languages." In Witzlack-Makarevich & Ernszt (eds.), Khoisan languages and linguistics: proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium, Riezlern / Kleinwalsertal (Research in Khoisan Studies 29). Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 – Chapter 1: Founding Provisions". gov.za. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ Haacke, Wilfrid H. G. (2018), Kamusella, Tomasz; Ndhlovu, Finex (eds.), "Khoekhoegowab (Nama/Damara)", The Social and Political History of Southern Africa's Languages, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 133–158, doi:10.1057/978-1-137-01593-8_9, ISBN 978-1-137-01592-1

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Khoekhoe languages". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ "Hottentot". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ Swingler, Helen (23 September 2020). "UCT launches milestone Khoi and San Centre". UCT News. University of Cape Town. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ↑ Hagman (1977)

- ↑ Haacke & Eiseb (2002)

- ↑ Haacke 1999

- ↑ Brugman 2009

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

H&E2was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ D. Beach, 1938. The Phonetics of the Hottentot Language. Cambridge.

- ↑ "Nama". phonetics.ucla.edu. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ↑ Tindal (1858) A grammar and vocabulary of the Namaqua-Hottentot language

- ↑ "Namibian town's plan to change name to !Nami#nus sparks linguistic debate". thestar.com. 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Haacke, Wilfrid H.G. (2013). "3.2.1 Namibian Khoekhoe (Nama/Damara)". In Vossen, Rainer (ed.). The Khoesan Languages. Routledge. pp. 141–151. ISBN 978-0-7007-1289-2.

- ↑ Hahn, Michael. 2013. Word Order Variation in Khoekhoe. In Müller, Stefan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Freie Universita t Berlin, 48–68. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.