Lake Baikal

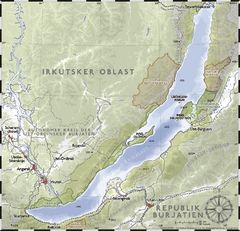

Lake Baikal is a huge lake in Siberia, Russia. It is the biggest fresh water reservoir in the world. The lake is near Irkutsk.

| Lake Baikal | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Coordinates | 53°30′N 108°0′E / 53.500°N 108.000°E |

| Lake type | Continental rift lake |

| Primary inflows | Selenge, Barguzin, Upper Angara |

| Primary outflows | Angara |

| Catchment area | 560,000 km2 (216,000 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Russia and Mongolia |

| Max. length | 636 km (395 mi) |

| Max. width | 79 km (49 mi) |

| Surface area | 31,722 km2 (12,248 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 744.4 m (2,442 ft)[1] |

| Max. depth | 1,642 m (5,387 ft)[1] |

| Water volume | 23,615.39 km3 (5,700 cu mi)[1] |

| Residence time | 330 years[2] |

| Shore length1 | 2,100 km (1,300 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 455.5 m (1,494 ft) |

| Frozen | January–May |

| Islands | 27 (Olkhon) |

| Settlements | Irkutsk |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Baikal is about 636 km (395 mi) long. It is 20 to 80 km (12 to 50 mi) wide. At its deepest point, it is 1,700 m (5,600 ft) deep. It is the deepest lake on Earth.[3][4] The lake is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It holds about 20% of the world's unfrozen surface fresh water.[5]

The lake has unique fish. It is home to more than 1,700 species of plants and animals. Two-thirds of them can be found nowhere else.[6]

Geology

changeLake Baikal fills an ancient rift valley, just as Lake Tanganyika does in East Africa. At the Baikal Rift Zone, the Earth's crust pulls apart.[7]

It is the deepest lake in the world at 1,642 m (5,387 ft). The bottom of the lake is 1,186.5 m (3,893 ft) below sea level, but below this lies some 7 km (4.3 mi) of sediment. This means the rift floor is 8–11 km (5.0–6.8 mi) below the surface: it is the deepest continental rift on Earth.[7]

In geological terms, the rift is young and active – it widens about two cm per year. The fault zone is also seismically active; there are hot springs in the area and notable earthquakes every few years.

Baikal's age is 25–30 million years. It is unique among large, high-latitude lakes, because its sediments have not been scoured by overriding continental ice sheets. U.S. and Russian studies of core sediment in the 1990s gave a detailed record of climatic variation over the past 250,000 years. Longer and deeper sediment cores are expected soon. Lake Baikal is the only confined freshwater lake in which evidence of gas hydrates exists.[8][9][10]

The lake is completely surrounded by mountains. The Baikal Mountains on the north shore and the taiga are protected as a national park. It has 27 islands; the largest, Olkhon, is 72 km (45 mi) long and is the third-largest lake-bound island in the world. The lake is fed by as many as 330 inflowing rivers.[5] It is drained through a single outlet, the Angara River.

Despite its great depth, the lake's waters are well-mixed and well-oxygenated throughout the water column, compared to the stratification that occurs in such bodies of water as Lake Tanganyika and the Black Sea.

Wildlife

changeLake Baikal has over 1000 species of plants[11] and 1550 species and varieties of animals. Over 60% of animals are endemic; of 52 species of fish 27 are endemic.

The omul fish (Coregonus autumnalis migratorius) is local to Lake Baikal. It is fished, smoked, and sold on all markets around the lake. For many travellers on the Trans-Siberian railway, purchasing smoked omul is one of the highlights of the long journey.

Baikal also has a species of seals, Baikal seal or nerpa. Bears and deer can be seen and hunted by the Baikal coast.

Ecosystem

changeIn 1986 Baikalskyi and Barguzinskyi became Biosphere Reserves.[12][13] The ecosystems are part of UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme.

Ecodangers

changeThe Baykalsk Pulp and Paper Mill was constructed in 1966 on the shoreline of Lake Baikal. The plant bleached paper using chlorine and discharged waste directly into Lake Baikal. The decision to construct the plant at Lake Baikal resulted in strong protests.[14] The objections of Soviet scientists had opposition from the industrial lobby. Only after decades of protest was the plant closed in 2008 (and only because it was unprofitable).[15][16] On 4 January 2010, production was resumed. On 13 January 2010, Russian President Vladimir Putin legalised the operation of the plant. This brought a wave of protests from ecologists and local residents.[17][18] In September 2013 the mill went bankrupt.[19]

Related pages

change- List of World Heritage Sites in Russia

- Marina Rikhvanova, an ecologist who works to protect Lake Baikal

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "A new bathymetric map of Lake Baikal. MORPHOMETRIC DATA. INTAS Project 99-1669.Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium; Consolidated Research Group on Marine Geosciences (CRG-MG), University of Barcelona, Spain; Limnological Institute of the Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Irkutsk, Russian Federation; State Science Research Navigation-Hydrographic Institute of the Ministry of Defense, St.Petersburg, Russian Federation". Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ↑ M.A. Grachev. "On the present state of the ecological system of lake Baikal". Lymnological Institute, Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ↑ "About Lake Baikal=--- details from the Encyclopedia". irkutsk.org. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ "Lake Baikal - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Lake Baikal: the great blue eye of Siberia". CNN. Archived from the original on 11 October 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- ↑ "Russia". Britannica Student Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The oddities of Lake Baikal". Alaska Science Forum. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ↑ Kuzmin M.I. et al 1998. First find of gas hydrates in sediments of Lake Baikal. Doklady Adademii Nauk, 362: 541–543 (in Russian).

- ↑ Vanneste M.; et al. (2001). "Multi-frequency seismic study of gas hydrate-bearing sediments in Lake Baikal, Siberia". Marine Geology. 172 (1): 1–21. Bibcode:2001MGeol.172....1V. doi:10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00117-1.

- ↑ Van Rensbergen P.; et al. (2002). "Sublacustrine mud volcanoes and methane seeps caused by dissociation of gas hydrates in Lake Baikal". Geology. 30 (7): 631–634. Bibcode:2002Geo....30..631V. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0631:SMVAMS>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ "WWW Irkutsk: Animals and fishes of Lake Baikal". irkutsk.org. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ World Network of Biosphere Reserves (WNBR), "Baikalskyi"; retrieved 2012-7-18.

- ↑ WNBR, "Barguzinskyi"; retrieved 2012-7-18.

- ↑ Sobisevich A. V., Snytko V. A. Some aspects of nature protection in the scientific heritage of academician Innokentiy Gerasimov // Acta Geographica Silesiana. 2018. Vol. 29, # 1. pp. 55–60.

- ↑ Tom Parfitt in Moscow (12 November 2008). "Russia Water Pollution". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "Sacred Land Film Project, Lake Baikal". Sacredland.org. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Clifford J. Levy (11 September 2010). "Russia Uses Microsoft to Suppress Dissent". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ↑ "Russians Debate Fate of Lake: Jobs Or Environment?". Npr.org. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Tide of discontent sweeps through Russia's struggling 'rust belt' – NBC News Archived 15 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Worldnews.nbcnews.com (30 November 2013). Retrieved on 15 May 2014.

Other websites

changeMedia related to Lake Baikal at Wikimedia Commons