Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was an American colonel in the United States Army. He became the General-in-chief of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.[1] He led the Army of Northern Virginia in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. He started out as an engineer but then moved up the ranks. Before the Civil War, Lee was an officer in the Mexican-American War. He was also head of West Point. As a colonel in the United States Army he led a battalion of marines to put down the rebellion at Harpers Ferry Armory and captured their leader, John Brown.[2]

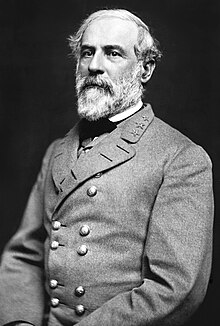

Robert Edward Lee | |

|---|---|

Lee in 1863 | |

| Born | Robert Edward Lee January 19, 1807 |

| Died | October 12, 1870 (aged 63) Lexington, Virginia |

| Resting place | Lee Chapel Washington and Lee University Lexington, Virginia |

| Occupation(s) | General, Confederate States of America |

| Spouse | Mary Custis |

| Children | 7 |

Early years

changeLee was born at Stratford Hall in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on January 19, 1807.[3] His parents were American Revolutionary War General and Governor of Virginia, Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee, and his wife, Anne Carter Lee.[4] In 1818, Lee's father died in the West Indies without ever seeing his son again.[4] Robert was raised by his mother in Alexandria, Virginia.[4]

Washington ancestry

changeLee and George Washington were both descendants of Augustine Warner, Sr. and his wife, Mary Towneley Warner.[5] Lee was descended through their daughter, Sarah. Washington was descended through their son, Augustine, Jr. Lee and Washington were third cousins, twice removed.[5]

Education

changeLee attended Eastern View, a school in Fauquier County, Virginia.[6] He may have attended schools in Shirley, Virginia, and in Alexandria, Virginia. His mother instructed him in the Episcopalian faith.[6] Lee attended the United States Military Academy at West Point, and graduated second in the class of 1829.[7]

Marriage

changeOn June 30, 1831, Lee married Mary Custis at Arlington House.[8] She was the granddaughter of George Washington's stepson, John Parke Custis.[9] They made their home at Arlington House. They had seven children.

Middle years

changeLee fought in the Mexican–American War under General Winfield Scott as a captain.[10] Later, Scott wrote about Lee calling him "the very best soldier I ever saw in the field."[10] After the war, Lee helped the army build forts. In 1855, Lee became a lieutenant colonel, and joined a cavalry regiment. As a Colonel, Lee was called on to stop the "slave rebellion", otherwise known as John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry.[10] Brown's raid was ended in less than an hour by Lee.[10]

Civil War

changeLee inherited a number of slaves with Arlington House.[11] He proved not to be a very good slave master.[11] He tried kindness and refused to use torture. But the slaves knew their freedom had been granted them in the will and refused to work.[11] Lee wanted to grant them their freedom but needed them to help him see out the work at Arlington House.[11] Personally, Lee hated slavery calling it an "evil" to both blacks and whites.[11] But he thought it had to be ended gradually or the economy of the South would wikt:collapse.[11] But Lee did agree with other Southerners thinking that blacks were inferior. He believed God would work out the problem in his own time.[11] Lee, like Thomas Jefferson had mixed feelings about slavery.[11]

The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 caused several states to secede in protest. This put Lee in a difficult position. The newly formed Confederate States of America offered Lee the rank of brigadier general.[4] Lee did not respond to the offer. Winfield Scott offered him command of the army of U.S. volunteers. He didn't answer this offer, either. Between April 12–14, 1861, U.S. troops were bombarded at Fort Sumter at Charleston, South Carolina. The same day Virginia seceded from the Union. Lee did not support secession but he could not fight his own state of Virginia.[4] Lee resigned his U.S. Army commission on April 22, 1861, at Arlington House.[8] He told his friends that he would not be a part of an invasion of the South.[12] Several days later he accepted command of all Virginia forces.[12]

At first, Lee did not command any soldiers in battle. Instead, he helped Confederate president Jefferson Davis make military decisions. In 1862, he became the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. He would lead the army for the rest of the war. He would win many battles, even though the Union army in the battles had more men and weapons. At the Battle of Gettysburg, he tried to invade the Union in order to end the war. But his army was defeated and he had to retreat back into Virginia.

During 1864 and 1865, Lee fought Union general Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia. During the end of 1864 and the beginning of 1865, Lee and Grant fought near Richmond, Virginia in a series of battles called the Siege of Petersburg. In April 1865, Grant forced Lee to retreat from Richmond. After a series of battles, Grant surrounded Lee near Appomattox Courthouse and forced Lee to surrender. Before he surrendered, he said "I would rather die a thousand deaths than surrender".

After the war

changePresident Andrew Johnson issued a proclamation granting amnesty and pardon to those Confederates who were a part of the rebellion against the United States.[13] It contained 14 exempted classes and members of these groups had to make an application to the President of the United States asking for a pardon.[13] Lee sent an application to General Grant. On June 13, 1865, Lee wrote to President Johnson:

"Being excluded from the provisions of amnesty & pardon contained in the proclamation of the 29th Ulto; I hereby apply for the benefits, & full restoration of all rights & privileges extended to those included in its terms. I graduated at the Mil. Academy at West Point in June 1829. Resigned from the U.S. Army April '61. Was a General in the Confederate Army, & included in the surrender of the Army of N. Va. 9 April '65."[13]

On October 2, 1865, Lee became president of Washington College in Virginia.[13] That same day Lee signed his Amnesty Oath as required by President Johnson. But Lee was not pardoned and his citizenship was not restored.[13]

His amnesty oath was found over a hundred years later in the National Archives.[13] It appears United States Secretary of State William H. Seward had given the application to a friend to keep as a souvenir.[13] The State Department had simply ignored Lee's application and it was never granted.[13] In a 1975 Joint resolution by the United States Congress, Lee's rights as a citizen were restored with the effective date of June 13, 1865.[13] The act was signed into law by President Gerald R. Ford on August 5, 1975.[13]

Lee died of heart failure on October 12, 1870. Washington College changed its name to Washington and Lee University in Lee's honor. Lee's birthday is celebrated in several southern states as a holiday.

Legacy

changeThis section does not have any sources. (July 2023) |

Robert E. Lee's legacy is complicated, and bring to mind a skilled military leader during the American Civil War, yet his association with the Confederacy raises ethical questions about his role in defending slavery. Opinions on his legacy vary, with some emphasizing his military tactics and others saying negative things and his allegiance to a cause rooted in maintaining slavery. It's a topic that has raised ongoing historical and moral discussions. However, historians engage in ongoing debates about Robert E. Lee's legacy. Some focus on his military prowess and strategic brilliance, while others examine his choice to fight for the Confederacy, a cause deeply entwined with slavery. These discussions often delve into the complexities of historical figures and the background of their actions.

References

change- ↑ "Robert E. Lee". American Studies. The University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ John C. Fredriksen, he United States Marine Corps: A Chronology, 1775 to the Present (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2011), p. 38

- ↑ "Robert E. Lee Biography". Bio. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Robert E. Lee". HistoryNet. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 The Papers of George Washington: Frequently Asked Questions, University of Virginia, 2011, archived from the original on 2005-11-20, retrieved June 23, 2013

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Emory M. Thomas, Robert E. Lee: A Biography (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997), p. 34

- ↑ Emory M. Thomas, Robert E. Lee: A Biography (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997), p. 52

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kenneth M. McFarland. "Arlington House". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ Roger Matuz; Bill Harris; Laura Ross, The President's Fact Book (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers; Workman Publishing Company, 2015), p. 15

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Biography: General Robert E. Lee". The American Experience. PBS/WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Brian C. Melton, Robert E. Lee: A Biography (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2012), p. 34

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Elizabeth Brown Pryor. "Robert E. Lee (ca. 1806–1870)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 "Pieces of History: General Robert E. Lee's Parole and Citizenship". Prologue Magazine. The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.