Extermination through labor

Extermination through labour is a way of torturing and killing prisoners. In a system of extermination by labour, prisoners are forced to do very heavy work without enough food or medical care. Eventually, prisoners die from malnutrition, illness, or injury.

Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union both had systems of extermination through labor. Some people describe North Korea's prison system as a system of extermination through labor.

Use as a term

changeThe term "extermination through labor" was first used during World War II. Most of the Nazi SS did not use the term (Vernichtung durch Arbeit in German). However, Albert Bormann, Joseph Goebels, Otto Georg Thierack, and Heinrich Himmler used the term during the fall of 1942, while talking about moving prisoners to concentration camps. Thierack and Goebbels specifically used the term.[1] The phrase was used again during the Nuremberg Trials after World War II ended.[1]

In the 1980s and 1990s, historians have argued over whether this term is appropriate. For example, Falk Pingel believed the phrase should not be applied to all Nazi prisoners. On the other hand, Hermann Kaienburg and Miroslav Kárný believed "extermination through labour" was one of the SS's specific goals. More recently, Jens-Christian Wagner has also argued that not all Nazi prisoners were targeted with death, so "extermination through labor" might not be the best way to describe the Nazis' goals for those prisoners.[1]

In Nazi Germany

changeVictims

changeDuring the Holocaust, the Nazis, led by Adolf Hitler, persecuted, tortured, and killed millions of people because of differences in race, ethnicity, politics, religion, sexual orientation, and disability.[2][3]

The Nazis also persecuted people who were "German-blooded," but who the Nazis thought of as "social misfits" (aisoziale). The Nazis said these people led useless "ballast-lives" (Ballastexiltenzen). These people included:

- Families with many children who depended on welfare

- People accused of being "vagrant" or "transient" (homeless)

- Alcoholics

- Prostitutes

- Homosexuals

The Nazis lists of these people and persecuted them in many ways. For example, some were forced to be sterilized. Many were eventually sent to prison camps for "extermination through labor." Along with them, anyone who spoke out against the Nazi regime (like communists, social democrats, democrats, and conscientious objectors) were sent to prison camps. Many of them did not survive.[2]

Extermination through labor was an important part of the Nazis' Final Solution - their plan to kill all the Jews in Europe.[4]

Concentration camps

changeConditions

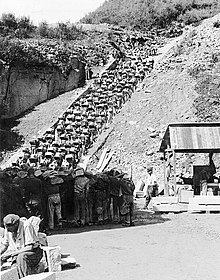

changeIn the Nazi prison camps, prisoners were treated like slaves:[2]

- They were not paid in any way

- Workers were constantly watched to prevent escape or rest

- Work was physically very hard (for example, building roads, working on farms, and working in factories, especially making weapons)

- Working hours were long (often 10–12 hours per day)

- Workers were fed very little

- Workers had very little hygiene, medical care, or needed clothing

Abuse and Torture

changeWorkers were also tortured and physically abused. For example, victims of Torstehen ("Gate Hanging") had to stand outside naked with their arms raised – like a gate hanging on its hinges. When they collapsed or passed out, they would be beaten until they re-assumed the position. Victims of Pfahlhängen ("Post Attachment") were tied with their hands behind their back and were hung by their hands on a tall stake. This would dislocate the prisoner's arm joints, and the pressure would be kill them within hours.

During the Holocaust, the Nazis built concentration camps and then extermination camps to imprison their victims. These "camps" were not just prisons. Their goal was not just to keep people locked up. Their goal was to torture and destroy people. All parts of camp life came along with humiliation and harassment. Forced labour was a part of this. Prisoners were whipped and treated like animals. Some forced labor was meant to help the German war machine grow. However, other prisoners were forced to do pointless heavy labor just to wear them down.[2] There were "no limits to working hours," according to official Nazi policy.[5]

Death rates

changeA slave worker on a work assignment usually lived less than four months, on average. Up to 25,000 of the 35,000 prisoners forced to work for IG Farben at Auschwitz concentration camp died.[6][7] Some died from exhaustion or disease. Others were killed after the Nazis decided they were not healthy enough to work any more.

Some work assignments were deadlier than others. Some prisoners were assigned to dig tunnels for German weapons factories during the last months of the war. About 30% of them died.[8] In the satellite camps, which were near mines and industrial firms, death rates were even higher. In these satellite camps, the supplies were often even less adequate than in the main camps.

The phrase "Arbeit macht frei" ("work shall set you free") appeared on the entry gates at Auschwitz and other Nazi labor camps.

In the Soviet Union

changeSome historians call the Soviet Gulag a system of death camps,[9][10][11][12] particularly in post-Communist Eastern European politics.[13] Other historians argue that this trivializes the Holocaust (makes the Holocaust seems like it was not so bad) because, at least after the war ended, a very large majority of people who entered the Gulag left alive.[14]

Alexander Solzhenitsyn introduced the expression camps of extermination by labour in his non-fiction work The Gulag Archipelago.[15] In the book, Solzhenitsyn argues that the Soviet Union beat its enemies by making them work as prisoners on big state-run projects (like the White Sea-Baltic Canal, quarries, remote railroads, and urban development projects) under terrible conditions. Roy Medvedev comments: "The penal system in the Kolyma and in the camps in the north was deliberately designed for the extermination of people."[12] Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev writes that Stalin was the "architect of the gulag system for totally destroying human life."[16]

According to formerly secret internal Gulag documents, some 1.6 million people must have died in the period between 1935 and 1956 in Soviet forced labour camps and colonies. This does not include people who died in prisoner-of-war camps. Most (about 900,000) of these deaths fell between 1941 and 1945.[17] At that time, World War II was ongoing, and food supplies were low in the entire country.

Russian historian Oleg Khlevniuk writes that about 500,000 people died in the camps and colonies from 1930 to 1941.[18] However, these figures do not include people who died in transport (on their way to the camps).[19] It also does not include the number of people who died shortly after their release due to the harsh treatment in the camps[20] (there were many of these people, according to both archives and memoirs).[21]

Historian J. Otto Pohl estimates that 2,749,163 prisoners died in the labour camps, colonies, and special settlements. He says this figure is incomplete.[22]

In 2010, Stanford historian Norman Naimark wrote a book called Stalin's Genocides. Naimark said scholars should change the word genocide so that it also meant killing people because they were in a social class or had political beliefs so that Stalin's killings would count as genocide.[23]

In North Korea

changeIt is believed that similar camps are operating in North Korea, and killed at least 20,000 political prisoners in 2013 alone, with at least 130,000 held therein.[24][25]

Related pages

change- Forced labour of Germans after World War II

- Hunger Plan, a German plan to starve the Slavic and Jewish populations

- Penal labour

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Buggeln, Marc (2014). Slave Labor in Nazi Concentration Camps. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-0-19-870797-4. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Gellately, Robert; Stoltzfus, Nathan (2001). Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany. Princeton University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-691-08684-2.

- ↑ Hitler's Ethic By Richard Weikar, page 73.

- ↑ Wannsee Protocol, January 20, 1942. Archived September 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine The official U.S. government translation prepared for evidence in trials at Nuremberg.

- ↑ IMT: Der Nürnberger Prozess. Volume XXXVIII, p. 366 / document 129-R.

- ↑ Auschwitz- Birkenau Muzeum. "The number of victims / History / Auschwitz-Birkenau". Auschwitz-Birkenau.

- ↑ Hilberg, Raul (1990). Die Vernichtung der europaischen Juden: Bd. 1. p. 994. ISBN 978-3-596-24417-1.

- ↑ Michael Zimmermann: Kommentierende Bemerkungen – Arbeit und Vernichtung im KZ-Kosmos. In: Ulrich Herbert et al. (Ed.): Die nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager. Frankfurt/M 2002, ISBN 978-3-596-15516-3, Vol. 2, p. 744

- ↑ Heinsohn, Gunnar (1998). Lexikon der Volkermorde. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-499-22338-9.

- ↑ Joel Kotek / Pierre Rigoulot Gefangenschaft, Zwangsarbeit, Vernichtung, Propyläen 2001

- ↑ Stettner, Ralf (1996). Archipel Gulag: Stalins Zwangslager.: Terrorinstrument und Wirtschaftsgigant. Entstehung, Organisation und Funktion des sowjetischen Lagersystems 1928 - 1956. ISBN 978-3-506-78754-5.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Medvedev, Roj Aleksandrovic (1973). Die Wahrheit ist unsere Starke: Geschichte und Folgen des Stalinismus. ISBN 978-3-10-050301-5.

- ↑ Pakier, Małgorzata; Strath, Bo (2013). A European Memory?: Contested Histories and Politics of Remembrance. Berghahn Books. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-85745-605-2.

- ↑ Hitler vs. Stalin: Who Killed More? | by Timothy Snyder | The New York Review of Books

- ↑ Alexander Solzhenitsyn Arkhipelag Gulag, Vol. 2. "Novyy Mir," 1990.

- ↑ Yakovlev, Alexander N. (2004). A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-300-10322-0.

- ↑ Кокурин, Александр (2000). ГУЛАГ, 1918-1960. p. 441. ISBN 978-5-85646-046-8.

- ↑ Khlevniuk, Oleg V.; Nordlander, David J. (2004). The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror. Yale University Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-300-09284-4.

- ↑ ibd., pp. 308–6.

- ↑ Ellman, Michael. Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments Europe-Asia Studies. Vol 54, No. 7, 2002, 1151–1172

- ↑ Applebaum, Anne (2003). Gulag: A History. Doubleday Books. p. 583. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1.

- ↑ Pohl, The Stalinist Penal System, p. 131.

- ↑ Cynthia Haven (September 23, 2010). "Stalin killed millions. A Stanford historian answers the question, was it genocide?". Stanford University. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ↑ Up to 20,000 North Korean prison camp inmates have 'disappeared' says human rights group - Telegraph

- ↑ Kerry calls for immediate shutdown of N. Korea's gulags

Further reading

change- Courtois, Stephane; Gauck, Joachim; Neubert, Ehrhart (1998). Das Schwarzbuch des Kommunismus: Unterdruckung, Verbrechen und Terror. ISBN 978-3-492-04053-2.

- Blank, Ralf; Echternkamp, Jorg (2004). Die Deutsche Kriegsgesellschaft, 1939 bis 1945: Politisierung, Vernichtung, Uberleben.

- Khlevniuk, Oleg V.; Nordlander, David J. (2004). The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09284-4.

- Кокурин, Александр (2000). ГУЛАГ, 1918-1960. ISBN 978-5-85646-046-8.

- Kotek, Joel.; Rigoulot, Pierre (2001). Das Jahrhundert der Lager: Gefangenschaft, Zwangsarbeit, Vernichtung. ISBN 978-3-549-07143-4.

- Sapper, Manfred (2004). Vernichtung durch Hunger: der Holodomor in der Ukraine und der UdSSR. ISBN 978-3-8305-0883-0.

- Kaienburg, Hermann (1990). Vernichtung durch Arbeit. Der Fall Neuengamme (Extermination through labour: Case of Neuengamme (in German). Bonn: Dietz Verlag J.H.W. Nachf. p. 503. ISBN 978-3-8012-5009-6.

- Gerd Wysocki (1992). Arbeit für den Krieg (Work for the War) (in German). Braunschweig.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bloxham, Donald (2001). Genocide on Trial: War Crimes Trials and the Formation of History and Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-19-820872-3.

- Nikolaus Wachsmann (1999). "Annihilation through labor: The Killing of State Prisoners in the Third Reich". Journal of Modern History. 71 (3): 624–659. doi:10.1086/235291. JSTOR 2990503. S2CID 154490460.

- various authors (2002). Michael Berenbaum, Abraham J Peck (ed.). The Holocaust and History: The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed, and the Reexamined. Indiana University Press. pp. 370–407. ISBN 978-0-253-21529-1.

- Kogon, Eugen; Heinz Norden; Nikolaus Wachsmann (2006). The Theory and Practice of Hell: The German Concentration Camps and the System Behind Them. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-374-52992-5.

Other websites

change- Lemo Die nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager Archived 2014-07-11 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- Frauen im Gulag, Deutschlandradio, May 11, 2003 Archived September 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (in German)