Kingdom of Lindsey

The Kingdom of Lindsey was in approximately what is now Lincolnshire. At the time of the Roman conquest of Britain, it was a part of the territory of the Corieltauvi tribe.[a] Lindsey appears in the 7th century list called the Tribal Hidage, where it is shown to be the same size as Essex and Sussex, all of which were set at 7,000 hides. It was a lesser Anglo-Saxon kingdom which was disputed over by Northumbria and Mercia. It ceased to exist as an independent kingdom during the reign of Offa of Mercia.

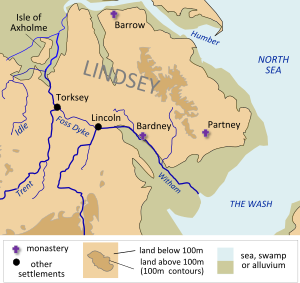

Geography

changeLindsey was between the River Humber on the north and the Witham on the south. To the east lay the North Sea and the west border was the River Trent. The Roman canal called Foss Dyke connected the Witham with the Trent on the southwestern border. Also to the west was Hatfield Chase, a low lying area of marshes.[1] This meant Lindsey was completely surrounded by water.[2] This led to the popular belief that Lindsey was an Island.[2]

History

changeThe name Lindsey comes from the word Lindissi (also spelled Lindesse and Lindesig).[3] Lindsey is a British name and not an Old English (or the Anglo-Saxon language) name.[1] Lindsey was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom but it had a strong Celtic population.[b][5] Lindsey seems to have been an independent kingdom with its own Celtic rulers for a time. It came under the control of Northumbria from c. 620–658.[c][6] Then it was subject to Mercia from c. 658–c. 675. It returned to Northumbrian control again from c. 675–679.[6] In 679 it was taken over by Mercia. Its kings were reduced in rank to Ealdormen.[6]

The conversion to Christianity in Lindsey began c. 631 by Paulinus.[7] Bishop Wilfrid was appointed the bishop of Northumbria, which included Lindsey, in 665. After a delay, he was installed as bishop in 669.[8] When he was expelled from Northumbria in 678, his diocese was divided up. Archbishop Theodore formed Lindsey into a separate diocese with its own bishop.[9] According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in the year 678 Eadhed was the first bishop of Lindsey.[10] In the 9th century, the Danes (Vikings) colonized Lindsey. This marked the end of the diocese of Lindsey.[9]

Hatfield

changeHaethfieldlande or Hatfield was another minor Anglo-Saxon kingdom listed in the Tribal Hidage.[11] Very little is known about Hatfield and nothing of its kings. Unlike other petty kingdoms in this area of Britain, the name here is of Anglo-Saxon origin and not British.[11] According to the Tribal Hidage, 'Hatfield-land' was merged with Lindsey into a single kingdom.[11] Afterwards it became known simply as Hatfield Chase, an area on the west part of Lindsey, later part of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. Hatfield was the site of a synod held by Theodore, the Archbishop of Canterbury c. 680. It was a royal residence of several kings of Northumbria. Edwin of Northumbria was killed here at the Battle of Hatfield Chase on 12 October 633.[12] Later, Hatfield became a part of the East Riding of Yorkshire.[11]

Anglian kings of Lindsey

changeThe Anglian collection is a collection of royal genealogies and regnal lists. It was put together during the reign of Alhred of Northumbria (765-774).[13] It records the kings of Deira and Bernicia (which became Northumberland), Mercia, Lindsey, Kent, East Anglia and Wessex.[13] These genealogies all trace back to Woden.[13] The most trustworthy name in the Lindsey genealogy is Caedbaed, according to most modern historians.[14] The family of Aldfrið is also considered fairly certain.[14] The other names are simply from the list with little or no additional information. The list of kings of Lindsey begins with:

- Critta (Crida) - Ruled in the 580s[6]

- Cueldgils[6]

- Caedbaed - Ruled c. 625. His name appears in Aldfrith's genealogy.

- Bubba[6]

- Beda[6]

- Biscop[6]

- Eanfruth[6]

- Eatta[6]

- Aldfrith - Ruled c. 775. Was the last king of Lindsey on record.[6]

None of dates are certain. With regard to Aldfrith, the witness list for an Anglo-Saxon charter includes an "Ealfrid rex". This dates to some time between 787 and 796.[15]

Notes

change- ↑ The Corieltauvi were a tribe of Britons living in the British Isles before and during the Roman conquest. Their capital was called Ratae Corieltauvorum, known today as Leicester.

- ↑ It has been a popular belief that the Anglo-Saxons drove Britons (Celts) away from the north and east of England. That those who remained became slaves of the Angles who invaded these lands. But recent historical and archaeological evidence shows just the opposite. Britons may have been in the majority of the population well after the coming of the Anglo-Saxons. Research into Lindsey shows the same thing.[4]

- ↑ It may have had a period of independence from 642–651.[6]

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Frank Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 49

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Castledyke South, Barton-on-Humber, eds. Gail Drinkall; Martin Foreman, Martin G. Welch (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), p. 7

- ↑ T. Green, ‘The British Kingdom of Lindsey’, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies, 56 (2008), p. 2

- ↑ Thomas Green, Britons and Anglo-Saxons: Lincolnshire AD 400-650 (Lincoln: History of Lincolnshire Committee, 2012), p. 602

- ↑ T. Green, ‘The British Kingdom of Lindsey’, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies, 56 (2008), p. 3

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Mike Ashley, The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens (New york: Carroll & Graf, 1999), p. 266

- ↑ Frank Merry Stenton; Doris Mary Stenton, Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England: Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970), p. 129

- ↑ E. B. Fryde; D. E. Greenway; et al., Handbook of British Chronology, Third Edition Revised (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 224

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Frank Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 48

- ↑ Benjamin Thorpe, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle according to the Several Original Authorities: Translation (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1861), p. 33

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 N. J. Higham, The Kingdom of Northumbria AD 350–1100 (Dover, NH: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1993), pp. 87–88

- ↑ Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, trans. Leo Sherley Price, revsd. R. E. Latham (London; New York: Penguin, 1990), p. 140

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, Second Edition, eds. Michael Lapidge, John Blair, et al. (Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), p. 205

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Thomas Green, Britons and Anglo-Saxons: Lincolnshire AD 400-650 (Lincoln: History of Lincolnshire Committee, 2012), p. 701

- ↑ Frank Merry Stenton; Doris Mary Stenton, Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England: Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970), pp. 129-31