Quark

A quark[1] is an elementary particle which makes up hadrons, the most stable of which are protons and neutrons. Atoms are made of protons, neutrons and electrons. It was once thought that all three of those were fundamental particles, which cannot be broken up into anything smaller, but after the invention of the particle accelerator, it was discovered that electrons are fundamental particles, but neutrons and protons are not. Neutrons and protons are made up of quarks, which are held together by gluons.[2]

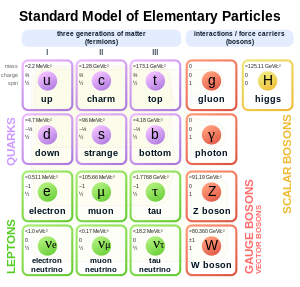

There are six types of quarks. The types are called flavours. The flavours are up (u), down (d), strange (s), charm (c), top (t), and bottom (b). Up, charm and top quarks have a charge of +2⁄3, while down, strange and bottom quarks have a charge of -1⁄3. Each quark has a matching antiquark. Antiquarks have a charge opposite to that of their quarks; meaning that up, charm and top antiquarks have a charge of -2⁄3 and down, strange and bottom antiquarks have a charge of +1⁄3.

Only up and down quarks are found inside of atoms of normal matter. Two up quarks and one down make a proton (2⁄3 + 2⁄3 - 1⁄3 = +1 charge) while two down quarks and one up make a neutron (2⁄3 - 1⁄3 - 1⁄3 = 0 charge). The other four flavours are not seen naturally on Earth, but they can be made in particle accelerators. Some of them may also exist inside of stars.

When two or more quarks are held together by the strong nuclear force, the particle formed is called a hadron. Quarks that make the quantum number of hadrons are named 'valence quarks'. The two families of hadrons are baryons (made of three valence quarks) and mesons (which are made from a quark and an antiquark). Some examples of baryons are protons and neutrons, and examples of mesons are pions and kaons.

When quarks are stretched farther and farther, the force that holds them together becomes bigger. When it comes to the point when quarks are separated, they form two sets of quarks, because the energy that is put into trying to separate them is enough to form two new quarks. So scientists think it is not possible to have one quark by itself.

Quarks also have color charge and react via the weak force. For baryons, each quark is green, red or blue. One can be one color at one time. For mesons, the quark is red, green or blue and the antiquark is antired (cyan), antiblue (yellow) or antigreen (pink). Quarks can change color by emitting a W boson. For example, if a green color-charged quark emits a red-antigreen W boson to a red quark, the green quark will become red and the red quark will become green. Therefore, W and Z bosons (which mediate the weak force for neutrinos) help particles react via the weak interaction.

This also causes the beta and beta-plus decay of atoms where a neutron decays into a proton, electron and electron antineutrino, and makes a proton turn into a neutron, positron and electron neutrino.

The idea (or model) for quarks was proposed by physicists Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig in 1964. Other scientists began searching for evidence of quarks, and succeeded in 1968 through the use of deep inelastic scattering; a process used to probe the inside of hadrons.

References

change- ↑ Named after a word from Finnegans Wake by James Joyce.

- ↑ Tong, David. 2017. Quantum fields. Royal Institution presentation. [1]

Other websites

change- Basic quark site Archived 2009-03-02 at the Wayback Machine