Ostrich

The ostrich (Struthio camelus) is a large flightless bird that lives in Africa. They are the largest living bird species, and have the biggest eggs of all living birds. Ostriches do not fly, but can run faster than any other bird.[3]

| Struthio camelus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| South African ostrich male (left) and females (S. camelus australis) | |||||

| Scientific classification | |||||

| Domain: | Eukaryota | ||||

| Kingdom: | Animalia | ||||

| Phylum: | Chordata | ||||

| Class: | Aves | ||||

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae | ||||

| Order: | Struthioniformes | ||||

| Family: | Struthionidae | ||||

| Genus: | Struthio | ||||

| Species: | S. camelus

| ||||

| Binomial name | |||||

| Struthio camelus | |||||

| Subspecies | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

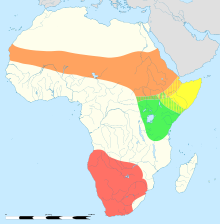

Struthio camelus distribution map

| |||||

They are ratites, a useful grouping of medium to large flightless birds. Ostriches have the biggest eyes of all land animals.[4][5]

Appearance

changeOstriches have long legs and a long neck, but they have a small head. Male ostriches have black feathers and female ostriches have gray and brown feathers. Both males and females have white feathers on their wings and tails. Male ostriches can be 1.8 - 2.7 meters / 6 – 9 feet tall, while female ostriches are 1.7 – 2 meters / 5.5 - 6.5 ft tall. They can run with a speed of about 65 kilometers per hour/40 miles per hour.

Habitat

changeOstriches now only live in Africa. They live in open grassland called savanna in the Sahel, and in parts of East Africa and south-west Africa. Some ostriches live in areas of the Sahara desert. There used to be ostriches in Middle East in the 20th century, but these went extinct in 1960 in Jordan.

Food

changeOstriches mainly eat plant matter, but they also eat insects. The plant matter consists of seeds, shrubs, grass, fruits and flowers while the insects they eat include locusts. Ostriches do not have teeth, and so cannot grind food as mammals do. Instead, they swallow pebbles. An adult ostrich carries about 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of stones in its gizzard, a special sac just before the stomach. The pebbles grind the food, and help its digestion. When eating, their gullet is filled with food. After that, the food is passed down their esophagus in the form of a ball called a bolus. The bolus may be as much as 210 ml (7.1 US fl oz). Ostriches can live without drinking for several days.

Behaviour

changeSocial behavior

changeOstriches normally spend the winter months in pairs or alone. During breeding season and sometimes during extreme rainless periods Ostriches live in nomadic groups of five to 50 birds (led by a top hen) that often travel together with other grazing animals, such as zebras or antelopes.[6]

With their acute eyesight and hearing, Ostriches can sense predators such as cheetahs from far away. When being pursued by a predator, they have been known to reach speeds in excess of 70 kilometres per hour (43 mph),[7] and can maintain a steady speed of 50 kilometres per hour (31 mph), which makes the Ostrich the world's fastest two-legged animal.[8] When lying down and hiding from predators, the birds lay their heads and necks flat on the ground, making them appear as a mound of earth from a distance. This even works for the males, as they hold their wings and tail low so that the heat haze of the hot, dry air that often occurs in their habitat aids in making them appear as a nondescript dark lump.

Ostriches can tolerate a wide range of temperatures. In much of their habitat, temperatures vary as much as 40 °C (72 °F) between night and day. Their temperature control mechanism relies on action by the bird, which uses its wings to cover the naked skin of the upper legs and flanks to conserve heat, or leaves these areas bare to release heat.

Reproduction

changeOstriches become sexually adults when they are 2 to 4 years old; females are adults about six months younger than males. The mating process differs in different places. Territorial males hiss and use other sounds to claim mating rights over a harem of two to seven hens.[9]

Fights usually last just minutes, but the ostriches can kill each other by slamming their heads into opponents. The winning male will then mates with all the females in the area, but he will only form a pair bond with the dominant female.

The females lay their eggs in one shared nest, a pit dug into the ground, 30 to 60 centimetres (12–24 in) deep and 3 metres (9.8 ft) wide.[10] The male ostrich digs the pit. The dominant female lays her eggs first, and when it is time to cover them to keep them warm, she pushes the eggs from the weakest females out. Most of the time, she leaves about 20 in most cases.[7]

Ostrich eggs are the largest of all eggs (and the yolk is the largest single cell),[11] but they are actually the smallest eggs relative to the size of the adult bird.[12] — on average they are 15 centimetres (5.9 in) long, 13 centimetres (5.1 in) wide, and weigh 1.4 kilograms (3.1 lb), over 20 times the weight of a chicken egg. The eggs are incubated by the females by day and by the males by night.[9] This uses the colouration of the two sexes to escape detection of the nest, as the drab female blends in with the sand, while the black male is nearly undetectable in the night.[13] The incubation period is 35 to 45 days.

Males and females cooperate in rearing chicks. The male defends the hatchlings and teaches them to feed. The survival rate is low for the hatchlings, with an average of one per nest surviving to adulthood.

Predators

changeWhen threatened, the ostrich will either hide itself by lying flat against the ground, or will run away. If cornered, it can attack with a kick from its powerful legs. Common predators of nests and young ostriches include jackals, various birds of prey, mongoose and vultures. Animals that prey on ostriches of all ages include cheetahs, lions, leopards, african dogs, and spotted hyena.[7][14] Ostriches can often outrun their predators in a pursuit and can even outpace cheetahs over long distances.[15] However, they may sometimes fight fiercely against predators, especially when chicks are being defended. They have sometimes killed lions in such fights.[3]

Evolution

changeThere is no doubt that the ratites are not a monophyletic group, because they are not descended from a single ancestor.[16] That means the taxonomy of the group is going to change, and they will not all be placed in the Order Struthioniformes as they have been. However, as ornothologists have not yet agreed on a new classification, for the time being the useful term 'ratites' is still used.

Unusual morphology

changeOstriches are likely to be placed alone in the order Struthioniformes. They have a number of peculiarities which suggest a separate evolution from the rest of the ratites. They lack a gallbladder.[17] They have three stomachs, and the caecum is 71 cm (28 in) long. Unlike all other living birds, the Ostrich secretes uric acid separately from faeces.[18] Unlike all other birds, who store the uric acid and faeces together, and excrete them together, ostriches store the faeces at the end of their rectum.[18] They also have unique pubic bones that are fused to hold their gut. Unlike most birds the males have a penis, which is retractable and 8 in (20 cm) long. Their palate (bone on the roof of the mouth) differs from other ratites.[7]

Ostriches and humans

changeOstriches are farmed in several countries. They used to be prized for their feathers, but are now farmed for their meat and eggs. Their skin can also be used to make leather.

In South Africa, hunters can get one group of feathers from one wild ostrich. When they are farmed, every seven or eight months farmers can take groups of feathers from the ostriches. They will grow back and can be collected again a in seven or eight more months.[19]

When threatened, Ostriches run away, but they can cause serious injury and death with kicks from their powerful legs.[6] Their legs can only kick forward.[20]

Ostriches reared entirely by humans may not direct their courtship behaviour at other Ostriches, but toward their human keepers.[21] Ostriches live 30 to 40 years on average.[6]

It is sometimes said that ostriches will hide their heads in the ground when they are scared or threatened, but this is not true.

Racing

changeIn some countries, people race each other on the back of Ostriches. The practice is common in Africa[22] and is relatively unusual elsewhere.[23] The Ostriches are ridden in the same way as horses with special saddles, reins, and bits. However, they are harder to manage than horses.[24]

Gallery

change-

A male (right) and a female (left).

-

A female ostrich.

-

A male.

-

An Ostrich egg.

References

change- ↑ BirdLife f Threatened Species (2016). "Struthio camelus: Bird Life International". 2016. IUCN: e.T45020636A95139620. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T45020636A95139620.en. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Brands, Sheila (14 August 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Genus Struthio". Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved 4 February 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Ostrich - National Geographic". animals.nationalgeographic.com. 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ↑ "San Diego Zoo's Animal Bytes: Ostrich". sandiegozoo.org. 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ↑ Schmidt, Amanda (27 September 2021). "Ostrich Fact Sheet". PBS.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Donegan, Keenan (2002). "Struthio camelus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Grzimek, Bernhard; Schlager, Neil (2003). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, Volume 8: Birds I. Gale Cengage. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- ↑ Desert USA (1996). "Ostrich". Digital West Media. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gilman, Daniel Coit; Colby, Frank Moore; Peck, Harry Thurston; Williams, Talcott (1903). The New international encyclopædia. Dodd, Mead and Company. pp. 497–498.

- ↑ Colin James Oliver Harrison; Alan Greensmith, Mark B. Robbins (1993). Birds of the World. DK Publishing (Dorling Kindersley). p. 39. ISBN 978-1-56458-295-9.

- ↑ Hyde, Kenneth (2004). Zoology: An inside view of animals (3rd ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing. p. 475. ISBN 978-0-7575-0170-8.

- ↑ Amazing bird records trails.com Archived 2017-06-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Nell, Leon (2003). The Garden Route and Little Karoo. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-86872-856-5.

- ↑ Animal Files theanimalfiles.com

- ↑ Largest eyes wildwatch.com Archived 2011-09-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Harshman, John; et al. (2008). "Phylogenetic evidence for multiple losses of flight in ratite birds" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (36): 13462–13467. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10513462H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803242105. PMC 2533212. PMID 18765814. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ↑ Marshall, Alan John 1960. Biology and comparative physiology of birds. Academic Press. p446

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Skadhauge E. et al. 2003. Does the ostrich (Struthio camelus) have the electrophysiological properties and microstructure of other birds?. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 134 (4): 749–755.

- ↑ "Africa—Cape of Good Hope, Ostrich Farm". World Digital Library. 1910–1920. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ Halcombe, John Joseph, ed. (1872). Mission life. Vol. 3 Part 1. London: William Macintosh. p. 304.

- ↑ BBC News (2003)

- ↑ Bradley, John H. (2009)

- ↑ Palosaari, Ben (2008)

- ↑ Mechanix Illustrated (1929)