Hummingbird

Hummingbirds are small birds of the family Trochilidae.

| Hummingbird | |

|---|---|

| |

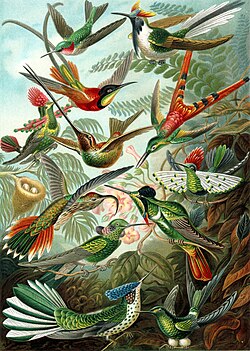

| A variety of hummingbirds from Ernst Haeckel's 1904 Kunstformen der Natur (Artforms of Nature) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | Trochiliformes

or Apodiformes |

| Family: | Trochilidae Vigors, 1825

|

They are among the smallest of birds: most species measure 7.5–13 cm (3–5 in). The smallest living bird species is the 2–5 cm bee hummingbird. They can hover in mid-air by rapidly flapping their wings 12–80 times per second (depending on the species). They are also the only group of birds able to fly backwards.[1] Their rapid wing beats do actually hum. They can fly at speeds over 15 m/s (54 km/h, 34 mi/h).[2]

Eating habits and pollination

changeHummingbirds help flowers to pollinate, though many other insects also do so. The hummingbird depends absolutely on the nectar, more so that any other bird.

Hummingbirds do not have a good sense of smell; instead, they are attracted to color, especially the color red. Unlike the butterfly, the hummingbird hovers over the flower as it drinks nectar from it, like a moth. When it does so, it flaps its wings very quickly to stay in one place, which makes it look like a blur and also beats so fast it makes a humming sound. A hummingbird sometimes puts its whole head into the flower to drink the nectar properly. When it takes its head back out, its head is covered with yellow pollen, so that when it moves to another flower, it can pollinate.

Like bees, hummingbirds can assess the amount of sugar in the nectar they eat. They reject flowers whose nectar has less than 10% sugar. Nectar is a poor source of nutrients, so hummingbirds meet their needs for protein, amino acids, vitamins, minerals, etc. by preying on insects and spiders.[3]

Feeding apparatus

changeMost hummingbirds have bills that are long and straight or nearly so, but in some species the bill shape is adapted for specialized feeding. Thornbills have short, sharp bills adapted for feeding from flowers with short corollas and piercing the bases of longer ones. The sicklebills' extremely decurved bills are adapted to extracting nectar from the curved corollas of flowers in the family Gesneriaceae. The bill of the fiery-tailed awlbill has an upturned tip, as in the Avocets. The male tooth-billed hummingbird has barracuda-like spikes at the tip of its long, straight bill.

The two halves of a hummingbird's bill have a pronounced overlap, with the lower half (mandible) fitting tightly inside the upper half (maxilla). When hummingbirds feed on nectar, the bill is usually only opened slightly, allowing the tongue to dart out into the nectar.

Like the similar nectar-feeding sunbirds and unlike other birds, hummingbirds drink by using grooved or trough-like tongues which they can stick out a long way.[4] Hummingbirds do not spend all day flying, as the energy cost would be prohibitive; much of their activity consists of sitting or perching. Hummingbirds feed in many small meals, consuming many small invertebrates and up to twelve times their own body weight in nectar each day. They spend an average of 10–15% of their time feeding and 75–80% sitting and digesting.

Co-evolution with flowers

changeSince hummingbirds are specialized nectar-eaters, they are tied to the flowers they feed upon.[5] Some species, especially those with unusual bill shapes such as the sword-billed hummingbird and the sicklebills, are co-evolved with a small number of flower species.

Many plants pollinated by hummingbirds produce flowers in shades of red, orange, and bright pink, though the birds will take nectar from flowers of many colors. Hummingbirds can see wavelengths into the near-ultraviolet. However, their flowers do not reflect these wavelengths as many insect-pollinated flowers do. The narrow color spectrum may make hummingbird-pollinated flowers inconspicuous to insects, thereby reducing nectar robbing by insects.[6][7]

Hummingbird-pollinated flowers produce relatively weak nectar (averaging 25% sugars w/w) containing high concentrations of sucrose, whereas insect-pollinated flowers typically produce more concentrated nectars dominated by fructose and glucose.[8]

Taxonomy

changeHummingbirds have traditionally been a part of the bird order Apodiformes. This order includes the hummingbirds, the swifts and the tree swifts. The Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy of birds, based on DNA studies done in the 1970s and 1980s, changed the classification of hummingbirds. Instead of being in the same order as the swifts, the hummingbirds were made an order, the Trochiliformes. Their previous order, Apodiformes was changed to the superorder Apodimorphae. This superorder contains the three families of birds which were in it when it was an order.

References

change- ↑ Ridgely, Robert S. and Paul G. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, volume 2, Field Guide, Cornell University Press.

- ↑ Clark and Dudley 2009. Flight costs of long, sexually selected tails in hummingbirds. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London.

- ↑ Not all sweetness and light

- ↑ Cade, Tom J. and Lewis I. Greenwald. Drinking behavior of mousebirds in the Namib desert, Southern Africa Archived 2011-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, The Auk, 83, #1, January 1966.

- ↑ Stiles, Gary (1981). "Geographical aspects of bird flower coevolution, with particular reference to Central America". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 68 (2): 323–351. doi:10.2307/2398801. JSTOR 2398801. S2CID 87692272.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Gironés, M.A.; Santamaría, L. (2004). "Why are so many bird flowers red?". PLOS Biol. 2 (10): e350. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020350. PMC 521733. PMID 15486585.

- ↑ Altschuler, D. L. (2003). "Flower color, hummingbird pollination, and habitat irradiance in four neotropical forests". Biotropica. 35 (3): 344–355. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2003.tb00588.x. S2CID 55929111.

- ↑ Nicolson, S.W. & Fleming, P. A. (2003). "Nectar as food for birds: the physiological consequences of drinking dilute sugar solutions". Plant Syst. Evol. 238 (1–4): 139–153. doi:10.1007/s00606-003-0276-7. S2CID 23401164.