Woodhenge

Woodhenge is a Neolithic henge and timber circle monument near Stonehenge. It is part of the UNESCO Stonehenge World Heritage Site in Wiltshire, 2 miles (3.2 km) north-east of Stonehenge.

Concrete pillars marking Woodhenge's postholes | |

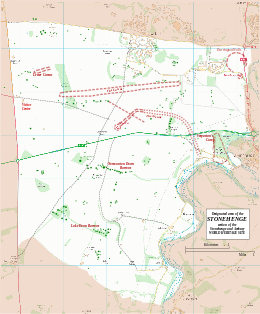

Map showing Woodhenge and Durrington Walls within the Stonehenge section of the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site | |

| Location | OS SU150434 |

|---|---|

| Region | Wiltshire |

| Coordinates | 51°11′22″N 1°47′09″W / 51.1894°N 1.78576°W |

| Type | henge |

| History | |

| Periods | Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1926-8 |

| Archaeologists | Ben and Maud Cunnington |

| Condition | feint earthworks, concrete posts |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | English Heritage |

| Designated | 1986[1] |

| Reference no. | 373 |

| Designated | 1929 |

| Reference no. | 1009133[2] |

The site

changeDiscovery

changeWoodhenge was identified in 1925 by an aerial archaeology survey.[3]

Date

changeThe structure was probably built during the period of the Beaker culture. This spanned both the late Neolithic and Britain's early Bronze Age.

The ditch has been dated to between 2470 and 2000 BC, which would be about the same time as, or slightly later than, construction of the stone circle at Stonehenge.[4] The timber monument was probably earlier. Radiocarbon dating of artifacts shows that the site was still in use around 1800 BC.[5]

Structure

changeThe site consists of six concentric oval rings of post holes, the outermost being about 43 by 40 metres (141 by 131 ft) wide. They are surrounded first by a single flat-bottomed ditch, 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) deep and up to 12 metres (39 ft) wide, and finally by an outer bank, about 10 metres (33 ft) wide and 1 metre (3.3 ft) high.[6] With an overall diameter measuring 110 metres (360 ft), the site had a single entrance to the northeast.[5]

At the center of the rings, was a crouched inhumation of a child, which Cunnington interpreted as a dedicatory sacrifice. After excavation, the remains were taken to London, where they were destroyed during the Blitz, making further examination impossible. Cunnington also found a crouched inhumation of a teenager in a grave dug in the Eastern section of the ditch, opposite the entrance.[6]

Most of the 168 post holes held wooden posts, although Cunnington found evidence that a pair of standing stones may have been placed between the second and third post hole rings. Recent excavations in 2006 have indicated that there were, in fact, at least five standing stones on the site,[4] arranged in a "cove". The deepest post holes measured up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) – and are believed to have held posts which reached as high as 7.5 metres (25 ft) above ground. Those posts would have weighed up to 5 tons, and their arrangement was similar to that of the bluestones at Stonehenge. The positions of the postholes are currently marked with modern concrete posts – a simple and informative method of displaying the site.

Further comparisons with Stonehenge were quickly noticed by Cunnington – both have entrances oriented approximately to the midsummer sunrise, and the diameters of the timber circles at Woodhenge and the stone circles at Stonehenge are similar.

Simple tracings were made of Maud Cunnington's and Professor Alexander Thom's plans of Woodhenge, which when folded to find its major axis of symmetry indicated that the monument may be aligned on the moon. A GPS survey made in 2008 produced the same result.[source?]

Relationship with other monuments

changeOver 40 years after the discovery of Woodhenge, another timber circle of comparable size was discovered in 1966. Known as the Southern Circle, inside of what came to be known as the Durrington Walls henge enclosure, only 70 metres (230 ft) north of Woodhenge.

It is likely that the timbers were freestanding, rather than part of a roofed structure.[4] For many years work on the study of Stonehenge had overshadowed any real breakthroughs in the understanding of Woodhenge. Ongoing investigations are part of the Stonehenge Riverside Project.

Theories have emerged in which the sites may all be integrated into an overall layout, in which the structures were linked by roads, and which incorporated the natural features of the River Avon. One suggestion is that the use of wood vs. stone may have held a special significance in the beliefs and practices involving the transformation between life and death.[6]

References

change- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage site No 373

- ↑ English Heritage Scheduled Monument record: Henge monuments at Durrington Walls and Woodhenge, a round barrow cemetery, two additional round barrows and four settlements[permanent dead link], accessed 24 January 2015

- ↑ Crawford 1929. Air-photography for archaeologists.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Woodhenge". World Heritage Site. English Heritage. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "History and Research: Woodhenge". www.english-heritage.org.uk. English Heritage. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Woodhenge". Pastscape. English Heritage. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

Other websites

change