Grignard reaction

This article uses too much jargon, which needs explaining or simplifying. (January 2024) |

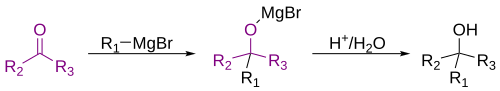

The Grignard reaction (pronounced /ɡriɲar/) is an organometallic chemical reaction in which alkyl- or aryl-magnesium halides (Grignard reagents) attack electrophilic carbon atoms that are present within polar bonds (for example, in a carbonyl group as in the example shown below). Grignard reagents act as nucleophiles. The Grignard reaction produces a carbon–carbon bond. It alters hybridization about the reaction center.[1] The Grignard reaction is an important tool in the formation of carbon–carbon bonds.[2][3] It also can form carbon–phosphorus, carbon–tin, carbon–silicon, carbon–boron and other carbon–heteroatom bonds.

It is a nucleophilic organometallic addition reaction. The high pKa value of the alkyl component (pKa = ~45) makes the reaction irreversible. Grignard reactions are not ionic. The Grignard reagent exists as an organometallic cluster (in ether).

The disadvantage of Grignard reagents is that they readily react with protic solvents (such as water), or with functional groups with acidic protons, such as alcohols and amines. Atmospheric humidity can alter the yield of making a Grignard reagent from magnesium turnings and an alkyl halide. One of many methods used to exclude water from the reaction atmosphere is to flame-dry the reaction vessel to evaporate all moisture, which is then sealed to prevent moisture from returning. Chemists then use ultrasound to activate the surface of the magnesium so that it consumes any water present. This can allow Grignard reagents to form with less sensitivity to water being present.[4]

Another disadvantage of Grignard reagents is that they do not readily form carbon–carbon bonds by reacting with alkyl halides by an SN2 mechanism.

François Auguste Victor Grignard discovered Grignard reactions and reagents. They are named after this French chemist (University of Nancy, France) who was awarded the 1912 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work.

Reaction mechanism

changeThe addition of the Grignard reagent to a carbonyl typically proceeds through a six-membered ring transition state.[5]

However, with steric hindered Grignard reagents, the reaction may proceed by single-electron transfer.

Grignard reactions will not work if water is present; water causes the reagent to rapidly decompose. So, most Grignard reactions occur in solvents such as anhydrous diethyl ether or tetrahydrofuran (THF), because the oxygen in these solvents stabilizes the magnesium reagent. The reagent may also react with oxygen present in the atmosphere. This will insert an oxygen atom between the carbon base and the magnesium halide group. Usually, this side-reaction may be limited by the volatile solvent vapors displacing air above the reaction mixture. Chemists may perform the reactions in nitrogen or argon atmospheres. In small scale reactions, the solvent vapours do not have enough space to protect the magnesium from oxygen.

Making a Grignard reagent

changeGrignard reagents are formed by the action of an alkyl or aryl halide on magnesium metal.[6] The reaction is conducted by adding the organic halide to a suspension of magnesium in an ether, which provides ligands required to stabilize the organomagnesium compound. Typical solvents are diethyl ether and tetrahydrofuran. Oxygen and protic solvents such as water or alcohols are not compatible with Grignard reagents. The reaction proceeds through single electron transfer.[7][8]

- R−X + Mg → R−X•− + Mg•+

- R−X•− → R• + X−

- X− + Mg•+ → XMg•

- R• + XMg• → RMgX

Grignard reactions often start slowly. First, there is an induction period during which reactive magnesium becomes exposed to the organic reagents. After this induction period, the reactions can be highly exothermic. Alkyl and aryl bromides and iodides are common substrates. Chlorides are also used, but fluorides are generally unreactive, except with specially activated magnesium, such as Rieke magnesium.

Many Grignard reagents, such as methylmagnesium chloride, phenylmagnesium bromide, and allylmagnesium bromide are available commercially in tetrahydrofuran or diethyl ether solutions.

Using the Schlenk equilibrium, Grignard reagents form varying amounts of diorganomagnesium compounds (R = organic group, X = halide):

- 2 RMgX R2Mg + MgX2

Initiation

changeMany methods have been developed to initiate Grignard reactions that are slow to start. These methods weaken the layer of MgO that covers the magnesium. They expose the magnesium to the organic halide to start the reaction that makes the Grignard reagent.

Mechanical methods include crushing of the Mg pieces in situ, rapid stirring, or using ultrasound (sonication) of the suspension. Iodine, methyl iodide, and 1,2-dibromoethane are commonly employed activating agents. Chemists use 1,2-dibromoethane because its action can be monitored by the observation of bubbles of ethylene. Also, the side-products are innocuous:

- Mg + BrC2H4Br → C2H4 + MgBr2

The amount of Mg consumed by these activating agents is usually insignificant.

The addition of a small amount of mercuric chloride will amalgamate the surface of the metal, allowing it to react.

Industrial production

changeGrignard reagents are produced in industry for use in place, or for sale. As with at bench-scale, the main problem is that of initiation. A portion of a previous batch of Grignard reagent is often used as the initiator. Grignard reactions are exothermic; this exothermicity must be considered when a reaction is scaled-up from laboratory to production plant.[9]

Reactions of Grignard reagents

changeReactions with carbonyl compounds

changeGrignard reagents will react with a variety of carbonyl derivatives.[10]

The most common application is for alkylation of aldehydes and ketones, as in this example:[11]

Note that the acetal function (a masked carbonyl) does not react.

Such reactions usually involve a water-based acidic workup, though this is rarely shown in reaction schemes. In cases where the Grignard reagent is adding to a prochiral aldehyde or ketone, the Felkin-Anh model or Cram's Rule can usually predict which stereoisomer will form.

Reactions with other electrophiles

changeIn addition, Grignard reagents will react with electrophiles.

Another example is making salicylaldehyde (not shown above). First, bromoethane reacts with Mg in ether. Second, phenol in THF converts the phenol into Ar-OMgBr. Third, benzene is added in the presence of paraformaldehyde powder and triethylamine. Fourth, the mixture is distilled to remove the solvents. Next, 10% HCl is added. Salicylaldehyde will be the major product as long as everything is very dry and under inert conditions. The reaction works also with iodoethane instead of bromoethane.[12][13][14]

Formation of bonds to B, Si, P, Sn

changeThe Grignard reagent is very useful for forming carbon–heteroatom bonds.

Carbon–carbon coupling reactions

changeA Grignard reagent can also be involved in coupling reactions. For example, nonylmagnesium bromide reacts with methyl p-chlorobenzoate to give p-nonylbenzoic acid, in the presence of Tris(acetylacetonato)iron(III), often symbolized as Fe(acac)3, after workup with NaOH to hydrolyze the ester, shown as follows. Without the Fe(acac)3, the Grignard reagent would attack the ester group over the aryl halide.[15]

For the coupling of aryl halides with aryl Grignards, nickel chloride in tetrahydrofuran (THF) is also a good catalyst. Additionally, an effective catalyst for the couplings of alkyl halides is dilithium tetrachlorocuprate (Li2CuCl4), prepared by mixing lithium chloride (LiCl) and copper(II) chloride (CuCl2) in THF. The Kumada-Corriu coupling gives access to [substituted] styrenes.

Oxidation

changeThe oxidation of a Grignard reagent with oxygen takes place through a radical intermediate to a magnesium hydroperoxide. Hydrolysis of this complex yields hydroperoxides and reduction with an additional equivalent of Grignard reagent gives an alcohol.

A reaction of Grignards with oxygen in presence of an alkene makes an ethylene extended alcohol. These are useful in synthesizing larger compounds.[16] This modification requires aryl or vinyl Grignard reagents. Adding just the Grignard and the alkene does not result in a reaction, showing that the presence of oxygen is essential. The only drawback is the requirement of at least two equivalents of Grignard reagent in the reaction. This can addressed by using a dual Grignard system with a cheap reducing Grignard reagent such as n-butylmagnesium bromide.

Nucleophilic aliphatic substitution

changeGrignard reagents are nucleophiles in nucleophilic aliphatic substitutions for instance with alkyl halides in a key step in industrial Naproxen production:

Elimination

changeIn the Boord olefin synthesis, the addition of magnesium to certain β-haloethers results in an elimination reaction to the alkene. This reaction can limit the utility of Grignard reactions.

Grignard degradation

changeGrignard degradation[17][18] at one time was a tool in structure identification (elucidation) in which a Grignard RMgBr formed from a heteroaryl bromide HetBr reacts with water to Het-H (bromine replaced by a hydrogen atom) and MgBrOH. This hydrolysis method allows the determination of the number of halogen atoms in an organic compound. In modern usage, Grignard degradation is used in the chemical analysis of certain triacylglycerols.[19]

Industrial use

changeAn example of the Grignard reaction is a key step in the industrial production of Tamoxifen.[20] (Tamoxifen is currently used for the treatment of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer):[21]

Gallery

change-

Magnesium turnings placed on a flask.

-

Covered with THF and a small piece of iodine added.

-

A solution of alkyl bromide was added while heating.

-

After completion of the addition, the mixture was heated for a while.

-

Formation of the Grignard reagent had completed. A small amount of magnesium still remained in the flask.

-

The Grignard reagent thus prepared was cooled to 0°C before the addition of carbonyl compound. The solution became cloudy since the Grignard reagent precipitated out.

-

A solution of carbonyl compound was added to the Grignard reagent.

-

The solution was warmed to room temperature. The reaction was complete.

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ Grignard, V. (1900), "Sur quelques nouvelles combinaisons organométaliques du magnésium et leur application à des synthèses d'alcools et d'hydrocabures", Compt. Rend., 130: 1322–1325

- ↑ Shirley, D.A. (1954), "The Synthesis of Ketones from Acid Halides and Organometallic Compounds of Magnesium, Zinc, and Cadmium", Org. React, 8: 28–58

- ↑ Huryn, D. M. (1991), "Carbanions of Alkali and Alkaline Earth Cations: (Ii) Selectivity of Carbonyl Addition Reactions", Comp. Org. Syn, 1: 49–75, doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-052349-1.00002-0, ISBN 9780080523491

- ↑ Smith, David H. (1999), "Grignard Reactions in "Wet" Ether", Journal of Chemical Education, 76 (10): 1427, Bibcode:1999JChEd..76.1427S, doi:10.1021/ed076p1427

- ↑ Maruyama, K.; Katagiri, T. (1989), "Mechanism of the Grignard reaction", J. Phys. Org. Chem, 2 (3): 205–213, doi:10.1002/poc.610020303

- ↑ Lai Yee Hing (1981), "Grignard Reagents from Chemically Activated Magnesium", Synthesis, 1981 (8): 585–604, doi:10.1055/s-1981-29537, S2CID 98124153

- ↑ Garst, J. F.; Ungvary, F. "Mechanism of Grignard reagent formation". In Grignard Reagents; Richey, R. S., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 2000; pp 185–275. ISBN 0-471-99908-3.

- ↑ Advanced Organic chemistry Part B: Reactions and Synthesis F.A. Carey, R.J. Sundberg 2nd Ed. 1983

- ↑ Philip E. Rakita (1996). "5. Safe Handling Practices of Industrial Scale Grignard Ragents" (Google Books excerpt). In Gary S. Silverman, Philip E. Rakita (ed.). Handbook of Grignard reagents. CRC Press. pp. 79–88. ISBN 0824795458.

- ↑ Henry Gilman and R. H. Kirby (1941). "Butyric acid, α-methyl". Org. Synth. Coll. Vol. 1: 361.

- ↑ Haugan, Jarle André; Songe, Pål; Rømming, Christian; Rise, Frode; Hartshorn, Michael P.; Merchán, Manuela; Robinson, Ward T.; Roos, Björn O.; Vallance, Claire (1997), "Total Synthesis of C31-Methyl Ketone Apocarotenoids 2: The First Total Synthesis of (3R)-Triophaxanthin." (PDF), Acta Chimica Scandinavica, 51: 1096–1103, doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.51-1096, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-11, retrieved 2009-11-26

- ↑ Wang, R. X et al. Synth. Commun. 1994, 24, 1757-1760.

- ↑ C. Ji ; Peters, D. G. Tetrahedron Letters, Volume 42, Issue 35, 27 August 2001, Pages 6065-6067 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040403901011789

- ↑ Peters, D. G.; C. Ji. J. Chem. Educ., 2006, 83 (2), p 290 http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ed083p290

- ↑ A. Fürstner; A. Leitner; G. Seidel (2004), "4-Nonylbenzoic Acid", Org. Synth., 81: 33–42

- ↑ Nobe, Youhei; Arayama, Kyohei; Urabe, Hirokazu (2005-12-01). "Air-Assisted Addition of Grignard Reagents to Olefins. A Simple Protocol for a Three-Component Coupling Process Yielding Alcohols". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (51): 18006–18007. doi:10.1021/ja055732b. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 16366543.

- ↑ Steinkopf, Wilhelm; Jacob, Hans; Penz, Herbert (1934), "Studien in der Thiophenreihe. XXVI. Isomere Bromthiophene und die Konstitution der Thiophendisulfonsäuren", Justus Liebig S Annalen der Chemie, 512: 136–164, doi:10.1002/jlac.19345120113

- ↑ Steinkopf, Wilhelm; V. Petersdorff, Hans-JüRgen (1940), "Studien in der Thiophenreihe. LI. Atophanartige Derivate des Dithienyls und Diphenyls", Justus Liebig S Annalen der Chemie, 543: 119–128, doi:10.1002/jlac.19405430110

- ↑ Myher JJ, Kuksis A (February 1979), "Stereospecific analysis of triacylglycerols via racemic phosphatidylcholines and phospholipase C", Can. J. Biochem., 57 (2): 117–24, doi:10.1139/o79-015, PMID 455112

- ↑ "Grignard Reagents: New Developments", ISBN: 0–471

- ↑ Jordan VC (1993), "Fourteenth Gaddum Memorial Lecture. A current view of tamoxifen for the treatment and prevention of breast cancer", Br J Pharmacol, 110 (2): 507–17, doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13840.x, PMC 2175926, PMID 8242225

Further reading

change- Rakita, Philip E; Gary S. Silverman, eds. (1996), Handbook of Grignard reagents, New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, ISBN 0-8247-9545-8

- Grignard knowledge: Alkyl coupling chemistry with inexpensive transition metals by Larry J. Westrum, Fine Chemistry November/December 2002, pp. 10–13 [1] Archived 2016-10-10 at the Wayback Machine