Mariano Taccola

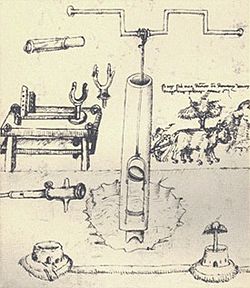

Mariano di Jacopo detto il Taccola (1381 – ca. 1453), called Taccola (the crow),[a] was an Italian artist, engineer and administrator. He lived during the early Renaissance period. He wrote two important books, De ingeneis and De machinis. These hand-drawn books have drawings of many new (for his time) machines. There are also descriptions of the machines. Leonardo da Vinci and other people used his books in the later Renaissance.

Life

changeMariano Taccola was born in Siena in 1381.[2][3] His father was a wine merchant named Jacopo.[1] His mother's name was Madonna Nofria (Bacci).[3] The name he was given at his baptism was Mariano Daniello.[4] Taccola himself used the name Ser Mariani Jacobi decti.[4] He had many different jobs. Records show Taccola had been a wood carver who made church ornaments.[2] He was a public official, a secretary to a hospital. Taccola was also a sculptor and an engineer. Most of the details about his life come from his books.[5] Taccola started his first book, De ingeneis, in 1419. He completed it in 1433.[5] The book probably led to his being appointed supervisor of roads and hydraulic engineering. He retired from this position sometime in the 1440s.[5] Taccola's second book, De machinis, appeared in 1449. It contained updated drawings from De ingeneis as well as many new drawings.[5] It appears he lived in Siena his entire life. Taccola received a pension from the city for his administrative work. In 1453 he stopped receiving his pension meaning he may have died that year.[5] But in another document dated 1453 he wrote he had become a friar in the "Order of San Jacomo".[6]

Taccola was one of the first artist-engineers of the Renaissance. He invented a new way of making technical drawings. This is called an exploded-view.[7] In these diagrams, an object's parts are shown separated and with indications of how they fit together. After Taccola died, his work was largely neglected until the 20th century.[8] Only after 1960 were his works printed. This was based on the discovery of his original works in two museums. These originals were much better than copies, which scholars had been familiar with.[8] Now their importance is more widely recognized.

Taccola was familiar with several sienese artists and architects. Jacopo della Quercia was his daughter's godfather.[9] He once interviewed the Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi and recorded it in one of his folios. Brunelleschi advised Taccola not to explain his inventions to others who did not understand machines. He said: "Therefore the gifts given to us by God must not be relinquished to those who speak ill of them and who are moved by envy or ignorance. To disclose too much of one's inventions and achievements is one and the same thing as to give up the fruit of one's ingenuity... the ignorant and inexperienced understand nothing, not even when things are explained to them; their ignorance moves them promptly to anger; they remain in their ignorance because they want to show themselves learned, which they are not"[10]

Facsimile editions

change- J.H. Beck, ed., 1969, Mariano di Jacopo detto il Taccola, Liber tertius de ingeneis ac edifitiis non usitatis, (Milan: Edizioni il Polifilo), 156 pp., 96 pls.

(This edition reproduces Books III and IV of de Ingeneis)

- Frank D. Prager and Gustina Scaglia, eds., 1971, Mariano Taccola and His Book "De ingeneis" (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press), 230 pp., 129 pls.

(This edition also reproduces Books III and IV of de Ingeneis)

- Gustina Scaglia, ed.,1971, Mariano Taccola, De machinis: The Engineering Treatise of 1449, 2 vols. (Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag), 181 and 210 pp., 200 pls.

Further reading

change- Donald Routledge Hill, 1996, A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times Routledge

- Lawrence Fane, 2003, "The Invented World of Mariano Taccola", Leonardo, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 135–143

- Scott Christianson, 2012, 100 diagrams that changed the world. A Plume Book/Penguin: New York, N.Y., p. 71

Notes

changeReferences

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Frank D. Prager; Gustina Scaglia; Mariano Taccola, Mariano Taccola and his Book De ingeneis (Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1972), pp. 3–4

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Francis C. Moon, The Machines of Leonardo Da Vinci and Franz Reuleaux: Kinematics of Machines from the Renaissance to the 20th Century (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 2007), pp. 131–133

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gerardo Doti (2008). "MARIANO di Iacopo". TRECCANI, LA CULTURA ITALIANA. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lawrence Fane, 'The Invented World of Mariano Taccola: Revisiting a Once-Famous Artist-Engineer of 15th-Century Italy', Leonardo, Vol, 36, No. 2 (MIT press, 2003), p. 136

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Daniel Coetzee, Philosophers of War: The Evolution of History's Greatest Military Thinkers (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2013), p. 247

- ↑ Lon R. Shelby, 'Mariano Taccola and His Books on Engines and Machines', Technology and Culture, Vol. 16, No. 3 (July 1975), p. 467

- ↑ Christianson, 2012, 100 diagrams that changed the world. A Plume Book/Penguin: New York, N.Y., p. 71.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lawrence Fane, 'The Invented World of Mariano Taccola', Leonardo Vol. 36, No. 2 (April 2003), pp. 135–143

- ↑ Lawrence Fane, 'The Invented World of Mariano Taccola: Revisiting a Once-Famous Artist-Engineer of 15th-Century Italy', Leonardo, Vol, 36, No. 2 (MIT press, 2003), pp. 136–137

- ↑ Frank D. Prager 'A Manuscript of Taccola, Quoting Brunelleschi, on Problems of Inventors and Builders', Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 112, No. 3 (June 21, 1968), pp. 141–142