Napoléon III

Napoléon III (20 April 1808 – 9 January 1873), also known as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, was the first President of the French Republic and the last monarch of France. Made president by popular vote in 1848, Napoleon III ascended to the throne on 2 December 1852, the forty-eighth anniversary of his uncle, Napoleon I's, coronation. He ruled as Emperor of the French until September 1870, when he was captured in the Franco-Prussian War.

| His Excellency Napoleon III The President of France | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Emperor of the French | |||||

| Reign | 2 December 1852 – 4 September 1870 | ||||

| Predecessor | Monarchy re-created Louis Philippe I as King of the French | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy abolished Louis Jules Trochu as President of the Government of National Defense'’ Adolphe Thiers | ||||

| Cabinet Chiefs | See list | ||||

| President of the French Republic | |||||

| In office | 20 December 1848 – 2 December 1852 | ||||

| Predecessor | Republic re-created Louis-Eugène Cavaignac as Chief of the Executive Power | ||||

| Successor | Republic abolished | ||||

| Prime Ministers | |||||

| Born | 20 April 1808 Paris, French Empire | ||||

| Died | 9 January 1873 (aged 64) Chislehurst, England | ||||

| Burial | St Michael's Abbey, England | ||||

| Spouse | Eugénie de Montijo | ||||

| Issue | Louis Napoléon, Prince Imperial | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Bonaparte | ||||

| Father | Louis I of Holland | ||||

| Mother | Hortense de Beauharnais | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

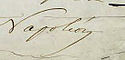

| Signature |  | ||||

Early life

changeNapoleon III, generally known as "Louis Napoléon" before he became emperor, was the son of Louis Bonaparte, brother of Napoléon. His mother was Hortense de Beauharnais, the daughter by the first marriage of Napoleon's wife Josephine de Beauharnais. Louis-Napoléon was a second son and a replacement child.[1] His older brother, Napoléon Charles Bonaparte, died at age four.[2] During Napoleon I's reign, Louis-Napoléon's parents had been made king and queen of a French puppet state, the Kingdom of Holland.

After Napoleon I's military defeats and deposition in 1815 and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in France, all members of the Bonaparte dynasty were forced into exile. Louis Napoleon was quietly exiled to the United States of America, and spent four years in New York City. He also visited Central America. He secretly returned to France and attempted yet another coup in August 1840, sailing with some hired soldiers into Boulogne. In 1844, his uncle Joseph died, making him the direct heir apparent to the Bonaparte claim. Two years later, his father Louis died, making Louis-Napoléon the clear Bonapartist candidate to rule France.

Louis-Napoléon lived within the borders of the United Kingdom until the revolution of February 1848 in France deposed Louis-Philippe I and established a Republic. He was now free to return to France, which he immediately did.

Ruler of France

changeIn 1848, he was elected President of France in a land slide victory. He won the election because of his popular name and French people hoped that he would return his uncle's glory. He used his rank as stepping stone to greater power. Finally in 1852, he crowned himself as Emperor Napoleon III and the Second French Empire was born. In 1856, Eugenie gave birth to a legitimate son and heir, Louis Napoléon, the Prince Impérial.

On 28 April 1855 Napoleon survived an attempted assassination. On 14 January 1858 Napoleon and his wife escaped another assassination attempt, plotted by Felice Orsini. Until about 1861, Napoleon's regime exhibited decidedly authoritarian characteristics, using press censorship to prevent the spread of opposition, manipulating elections, and depriving the Parliament of the right to free debate or any real power. His foreign policy included support for Maximilian I of Mexico.

A far more dangerous threat to Napoleon, however, was looming. France saw its dominance on the continent of Europe eroded by Prussia's crushing victory over Austria in the Austro-Prussian War in June–August 1866. To prevent Prussia under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck becoming even more powerful, Napoleon began the Franco-Prussian War. This war proved disastrous, and was instrumental in giving birth to the German Empire, which would take France's place as the major land power on the continent of Europe. In the 1870 Battle of Sedan Prussian forces captured the Emperor. The forces of the Third Republic deposed his government in Paris two days later.

Death

changeThis section does not have any sources. (January 2024) |

Napoleon spent the last few years of his life in exile in England, with Eugenie and their only son. The family lived at Camden Place Chislehurst (then in Kent), where he died on 9 January 1873. He was haunted to the end by bitter regrets and by painful memories of the battle at which he lost everything.

Napoleon was originally buried at St. Mary's, the Catholic Church in Chislehurst. However, after his son died in 1879 fighting in the British Army against the Zulus in South Africa, the bereaved Eugenie decided to build a monastery. The building would house monks driven out of France by the anti-religious laws of the Third Republic, and would provide a suitable resting place for her husband and son.

Legacy

changeAn important legacy of Napoleon III's reign was the rebuilding of Paris under the supervision of Georges-Eugène Haussmann. One purpose was reduce the ability of future revolutionaries to challenge the government by blocking the small, medieval streets of Paris with barricades. However, the main reason for the complete transformation of Paris was Napoleon III's desire to modernize Paris based on what he had seen of the modernizations of London during his exile there in the 1840s.

Although an authoritarian ruler who used surveillance and censorship to stifle any opposition, a wide range of reforms were carried out during the time Napoleon III led France. Amongst other reforms, these included the establishment of hospitals, nurseries, orphanages, retirement plans, insurance schemes, and price controls on bread.[3]

Regulations for the prevention of food adulterations were introduced, along with the transfer of taxes from necessaries to luxuries, the assurance of Christian burial to the poorest Christian, and increased pay and honour to the lower ranks of the army and to the private soldier.[4]

Public assistance was encouraged, while a law of 1864 legalised strikes although not trade unions. Substantial contributions were also made by Napoleon to a fund to develop worker’s cooperatives.[5]

Other laws originated and institutions founded by Napoleon included the organisation of public baths and lavatories, maternity societies to provide attendance on poor women at their houses during childbirth, orphanages, refuges for old age, the Convalescent Institution at Vincennes, the Asylum for Incurables at Vesinet, a retiring fund for the poorer assistant clergy, loan societies to make provision for their members in sickness, and for their widows and orphans, and a law for improving the dwellings of the working classes. A decree was also issued providing for the observance of Sunday rest in all public works.[6]

In 1851, some enactment was introduced for providing the indigent with legal assistance.[7] Another law from that year regulated assistance for the needy.[8] Napoleon also authorized several cooperatives and moderate unions, supported welfare institutions like orphanages, nurseries and aid for accident victims and encouraged the first adult education programs for workers.[9]

Titles and styles

change- 20 April 1808 – 9 July 1810: His Imperial and Royal Highness Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, Prince of Holland

- 20 April 1808 – 25 July 1846: His Imperial Highness Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, Prince Imperial of France

- 20 December 1848 – 2 December 1852: His Excellency Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, President of the French Republic ("fr: Le Prince-President")

- 2 December 1852 – 4 September 1870: His Imperial Majesty the Emperor of the French

- 4 September 1870 – 9 January 1873: His Imperial Majesty the former Emperor of the French

References

change- ↑ Edges of Experience: Memory and Emergence : Proceedings of the 16th International Congress for Analytical Psychology, ed. Lyn Cowan (Einsiedeln Switzerland: Daimon, 2006), p. 786

- ↑ Henry Walter De Puy, Louis Napoleon and the Bonaparte Family: Comprising a Memoir of Their (New York: C.M. Saxton, 1859), p. 60

- ↑ The Lost History of Liberalism From Ancient Rome to the Twenty-First Century By Helena Rosenblatt, 2020, P.158

- ↑ The life of Napoleon III Volume III by Blanchard Jerrold, P.370

- ↑ Napoleon III By James F. Mcmillan, 2014, P.142

- ↑ Life of Napoleon III By Pascoe Grenfell Hill, 1869, P.116-117

- ↑ Legal Aid Catalyst for Social Change By Raman Mittal, 2012, P.124

- ↑ Migration in European History By Klaus Bade, 2008, P.150

- ↑ The Course of French History By Pierre Goubert, 2002, P.261