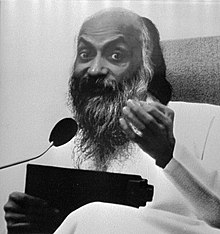

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh

Rajneesh (11 December 1931 – 19 January 1990) was an Indian mystic, guru, and spiritual teacher. Among many gurus who brought forms of yoga to the West, he is one of the most notable. He freely invented yogic and tantric practices, characteristics of Neo-Hinduism that began to emerge in the 1870s.[1] His international following has continued after his death. Rajneesh was born Chandra Mohan Jain; he was known as the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh during the 1970s and 1980s, and finally as Osho in the last year of his life.

Rajneesh | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Chandra Mohan Jain 11 December 1931 Kuchwada Village, Bareli Tehsil, Raisen Distt. Bhopal State, British India (modern day Madhya Pradesh, India) |

| Died | 19 January 1990 (aged 58) Pune, Maharashtra, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Known for | Spirituality |

| Notable work | Many books, audio and video tapes (exact number not known) |

| Movement | Jivan Jagruti Andolan; Neo-sannyas |

Early life

changeHe was born in a small village in the Gadarwara town of Narsinghpur District of Madhya Pradesh state in north India. He spent most of his childhood with his maternal grandparents, which he later mentioned as "the blessing in his life" for its carefree environment.

He entered college at his age of nineteen. Asked by the principal to leave the college, he transferred to D.N. Jain College and completed his B.A. in philosophy in 1955. After obtaining his M.A. in philosophy in University of Sagar in 1957, he started teaching at Raipur Sanskrit College and became a professor at Govt. Mahakaushal Mahavidyalaya, Pachpedhi, Jabalpur affiliated to Jabalpur University in 1960 now known as Rani Durgavati vishwavidyalaya. While teaching at colleges, he became known as a public speaker. He resided in a rented house on Garha Road leading from Ranital Crossing to Garha sub-town around 1957-59 period in a simple house and did all his routine work by himself. In those days he used to meditate in Bhawar Tal Park of Jabalpur City under the "Maulshri" tree which is still preserved and known as "Osho Tree" in the Park. (based on personal knowledge as a student of Mahakaushal College (now Govt, College of Arts & Science) 1956-60.

Academic

changeAs a professor of philosophy, he traveled throughout India in the 1960s as a public speaker. He was a critic of socialism, Mahatma Gandhi, and other stalwarts of Indian politics, including institutionalised religions. He advocated a more open attitude towards sexuality: so the press called him a "sex guru".[2] In 1970, he settled for a time in Bombay initiating disciples, known as neo-sannyasins, and expanded his spiritual teaching and work. In his discourses, he reinterpreted writings of religious traditions, mystics, and philosophers from around the world. Moving to Poona in 1974,[3] he established an ashram that attracted increasing numbers of Westerners.

Ashrams

changePoona

changeThe Poona ashram was by all accounts an exciting and intense place to be, with an emotionally charged, madhouse-carnival atmosphere.[4][5][6] The day began at 6:00 a.m. with Dynamic Meditation.[7][8] From 8:00 a.m., Rajneesh gave a 60- to 90-minute spontaneous lecture in the ashram's "Buddha Hall" auditorium, commenting on religious writings or answering questions from visitors and disciples.[4][8] Until 1981, lecture series held in Hindi alternated with series held in English. During the day, various meditations and therapies took place, whose intensity was ascribed to the spiritual energy of Rajneesh's "buddhafield".[5] In evening darshans, Osho conversed with individual disciples or visitors and initiated disciples ("gave sannyas").[4][8]

The ashram offered therapies derived from the Human Potential Movement to its Western audience and made news in India and abroad, chiefly because of its permissive climate and Osho's provocative lectures. By the end of the 1970s, there were mounting tensions with the Indian government and the surrounding society.

A situation rose when Rajneesh entered a three-and-a-half-year period of self-imposed public silence on 10 April 1981. He occupied himself with satsangs—silent sitting with music and readings from spiritual works, and gave no discourses.[2][8] Around the same time, Ma Anand Sheela replaced Ma Yoga Laxmi as Rajneesh's secretary.[6]

Oregon

changeLater in 1981 Rajneesh moved to the United States, and his followers established a community, later known as Rajneeshpuram, in the state of Oregon. Within a year, the leadership of the commune became embroiled in a conflict with local residents, primarily over land use, which was marked by hostility on both sides. Rajneesh lived in a trailer next to a covered swimming pool and other amenities. He did not lecture and only saw most of the residents when, daily, he would slowly drive past them as they stood by the road. He gained public notoriety for the many Rolls-Royces bought for his use, eventually numbering 93 vehicles.[9][10] This made him the largest single owner of the cars in the world.[11]

Influence of Ma Anand Sheela

changeMa Anand Sheela (born Sheela Ambatal Patel, 28 December 1949) was Rajneesh's personal secretary from 1981 to 1985. On 10 July 1981, she purchased the 64,000-acre (260 km2) Big Muddy Ranch to create the Rajneeshpuram, Oregon commune.[12][13] She was the main manager and spokesperson. She carried a .357 Magnum handgun, and created a Rajneeshpuram police force armed with Uzi submachine guns and a Jeep-mounted .30-calibre machinegun.[14][15] It was under Sheela's influence that Rajneesh decided to travel to the United States and begin an ashram there.[13]

While at Rajneeshpuram, Rajneesh depended on Sheela to manage the organisation.[13] She was seen as Rajneesh's principal aide, and as second-in-command of the organisation. She was also president of Rajneesh Foundation International. The two of them met each day in private to go over significant matters for the group.[13]

Sheela ran the operations of virtually all of the sub-groups under Rajneesh's movement, as well as Rajneeshpuram itself.[13] Rancho Rajneesh was administered through the inner circle of followers managed by Sheela.[13] She made decisions for the organisation in meetings with followers in her own private living space.[13] In addition, Sheela would make decisions for the organisation by herself or after meeting with Rajneesh.[13] Those followers of Rajneesh that did not abide by her rulings risked being kicked out of Rajneeshpuram.[13] According to Bioterrorism and Biocrimes, "This peculiar decision-making style had a significant impact on the group's move to employ biological agents".[13]

The Oregon commune collapsed in 1985 when Rajneesh revealed that the commune leadership had committed a number of serious crimes, including a 1984 bioterror attack (food contamination) on the citizens of The Dalles, Oregon.[16] He was arrested shortly afterwards and charged with immigration violations, and was deported from the United States in accordance with a plea bargain.[17][18][19]

Ma Anand Sheela was sentenced to three concurrent 20-year prison sentences, for assault, attempted murder, telephone tapping, immigration fraud and product tampering.[20] She served 29 months before being released on parole.[21] Upon release, she left immediately for Switzerland, where she now manages two nursing homes.

After the collapse

changeTwenty-one countries denied him entry, causing Osho to travel the world before returning to Poona, where he died in 1990. His ashram is today known as the Osho International Meditation Resort. His teachings emphasised the importance of meditation, awareness, love, celebration, courage, creativity and humour—qualities that he viewed as being suppressed by adherence to static belief systems, religious tradition and socialisation. Osho's teachings have had an impact on Western New Age thought,[22][23]p177 and their popularity has increased since his death.[23][24]p182

One of his strong hopes was creating what he called "new man", who embodies characteristics of Gautama Buddha and Zorba the Greek [25] at the same time. Through this concept, Rajneesh tried to reject neither science nor spirituality, but embrace them both. According to him, “New man” is not subject to one’s sex and does not belong to institutions such as family, political ideologies, or religions.

Books by Rajneesh

changeMany books of his teachings were published. They followed a pattern: he would give talks, they would be recorded. The tapes would be worked up into a typed manuscript by some of his followers. The manuscripts would be published, at first in India, and without ISBN numbers, so they were at first bought by his admirers. Later some of the best were reprinted in the West. His talks covered a wide range of religions and philosophies. The total number of books is not known, but it was certainly more than 30.[26]

- 1974 The book of the secrets I: discourses on Vigyana Bhairava Tantra. The Rajneesh Foundation, Poona, India. Reprinted 1976 by Thames & Hudson, London. ISBN 0 500 27076 7. This book is about meditation, and there were four more volumes.

- 1975. Roots and wings: talks on Zen. Rajneesh Foundation, Poona, India.

- 1975. And the flowers showered: talks on Zen. Rajneesh Foundation, Poona, India.

- 1976. The hidden harmony: discourses on the fragments of Heraclitus. Rajneesh Foundation, Poona, India.

- 1976. When the shoe fits: talks on Chuang Tzu. Rajneesh Foundation, Poona, India.

- 1977. Ancient music in the pines: talks on Zen stories. Rajneesh Foundation, Poona, India.

listed without dates:

- The ultimate alchemy, vols I & II.

- Yoga: the alpha and the omega. vols I and II

- Vedanta: seven steps to the Samadhi.

- The way of the white cloud.

- No water no moon: talks on Zen. (UK edition Sheldon Press)

- The mustard seed: discourses on the sayings of Jesus.

- Neither this nor that: discourses on Sosan–Zen

- Tantra: the supreme understanding. (U.S. edition: Only one sky)

- Just like that: discourses on Sufi stories.

- Until you die: discourses on Sufi stories.

- I am the gate. Harper & Row, New York.

- The inward revolution.

- TAO: the three treasures: discourses on Lao Tzu, vols I–IV.

- Tantra, spirituality and sex. Published in the U.S.A.

- Meditation: the art of ecstasy. Harper & Row, New York.

- Come follow me: discourses on the life of Jesus.

References

change- ↑ Smith, David. “Hinduism.” Religions in the Modern World: Traditions and Transformations, by Linda Woodhead et al., 3rd ed., Routledge, 2016, pp. 57–59.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Joshi, Vasant 1982. The Awakened One. San Francisco, CA: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-064205-X

- ↑ these moves were funded by support from a few of his wealthiest female followers.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 FitzGerald, Frances 1986. Rajneeshpuram, The New Yorker

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Fox, Judith M. 2002. Osho Rajneesh. Studies in Contemporary Religion Series, #4, Salt Lake City: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-156-2

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gordon, James S. 1987. The Golden Guru. Lexington, MA: Stephen Greene Press. ISBN 0-8289-0630-0

- ↑ Aveling, Harry 1994. The Laughing Swamis. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1118-6

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Mullan, Bob 1983. Life as laughter: following Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7102-0043-9

- ↑ Aveling, Harry (ed) 1999. Osho Rajneesh and his disciples: some western perceptions. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (includes studies by Susan J. Palmer, Lewis F. Carter, Roy Wallis, Carl Latkin, Ronald O. Clarke and others previously published in various academic journals) ISBN 81-208-1599-8

- ↑ Pellissier, Hank (14 May 2011). "The Bay Citizen: Red Rock Island". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ Ranjit Lal, (16 May 2004). A hundred years of solitude. The Hindu. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ Oregon Historical Society, 2002

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 Carus, W. Seth 2002. Bioterrorism and biocrimes: the illicit use of biological agents since 1900. Fredonia Books, 51. ISBN 1-4101-0023-5

- ↑ Coster P. 10 May 1985. A Pistol-Packin' Sheela with a tongue to match. The Courier-Mail.

- ↑ Turner, G. (10 May 1985). "Bhagwan hits out as Commune chiefs flee". The Courier-Mail.

- ↑ FitzGerald, Frances 1986b. "Rajneeshpuram", The New Yorker

- ↑ Latkin, Carl A. 1992. Seeing Red: a social-psychological analysis. Sociological Analysis 53 (3): Pages 257–271, doi:10.2307/3711703, reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 337–361.

- ↑ Staff. "Wasco County History". Oregon Historical County Records Guide. Oregon State Archives. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ↑ Staff (1990). "Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh". Newsmakers 1990. Gale Research. pp. Issue 2.

- ↑ Tucker, Jonathan B. 2000. Toxic terror: assessing terrorist use of chemical and biological weapons. The MIT Press, 126. ISBN 0-262-70071-9.

- ↑ Carter, Lewis F. 1990. Charisma and control in Rajneeshpuram. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38554-7

- ↑ Heelas, Paul 1996. The New Age movement: religion, culture and society in the age of postmodernity. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 40, 68, 72, 77, 95–96. ISBN 0-631-19332-4

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Forsthoefel, Thomas A.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (eds) 2005. Gurus in America. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-6574-8

- ↑ Urban, Hugh B. 2003. Tantra: sex, secrecy, politics, and power in the study of religion. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23656-4

- ↑ from the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis

- ↑ Ancient music in the pines dated December 1977, lists 28 titles (some with four or five volumes). There were definitely more published after that date.

Further reading

change- Osho (2000), Autobiography of a spiritually incorrect mystic, New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-25457-1.

- Carrette, Jeremy; King, Richard (2004), Selling spirituality: the silent takeover of religion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-41530-209-9.