Ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer is cancer that involves different regions of the ovary. (The female reproductive system usually contains two ovaries, one on each side of the uterus.) Changes that happen in the Fallopian tube(s) may be related to the cancer. (The female reproductive system usually contains two fallopian tubes, one for each ovary.) Other types of ovarian cancer involve egg cells.

| Ovarian cancer | |

|---|---|

| |

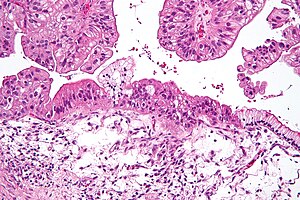

| Micrograph of a mucinous ovarian carcinoma stained by H&E | |

| Medical specialty | Oncology, gynecology |

| Symptoms | Early: vague[1] Later: bloating, pelvic pain, constipation, abdominal swelling, loss of appetite[1] |

| Usual onset | Usual age of diagnosis 63 years old[2] |

| Types |

|

| Risk factors | Never having children, hormone therapy after menopause, fertility medication, obesity, genetics[4][5][6] |

| Diagnostic method | Tissue biopsy[1] |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy[1] |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rate c. 49% (US)[7] |

| Frequency | 1.2 million (2015)[8] |

| Deaths | 161,100 (2015)[9] |

Ovarian cancer is a particularly difficult cancer for at least four reasons:

- It usually does not have early signs (symptoms).

- The symptoms that may eventually occur are the same symptoms that can happen with many other very common medical problems.

- Ovarian cancer often starts spreading to other parts of the body very soon after it starts.

- There are no truly useful ("efficacious") screening methods (tests) for ovarian cancer.

The unfortunate result is that when it is found, this cancer is often already at a late stage, meaning it has existed for some time and is very difficult to treat. A woman's risk of getting ovarian cancer during her lifetime is about 1 in 87.[10] Worldwide, there are more than 313,000 new cases of ovarian cancer every year.[11]

Some of the risk (chance) of getting ovarian cancer is linked to the foods a woman eats. That is a modifiable (changeable) risk factor, meaning a woman can change her chance of getting ovarian cancer depending on what foods she eats. About 10% of the risk of getting ovarian cancer is because of family history. Researchers think that some chemicals may increase the risk of getting ovarian cancer. This is difficult to prove, but chemicals such as pesticides, herbicides, plastics (especially those that the body can confuse with hormones), air pollution, water pollution (especially in drinking water) and radiation (naturally-occurring or medical) are known to cause some cancers. For ovarian cancer, it appears that the largest risk is simply chance. Once in a while, a tiny mistake occurs in the body. The more egg-release cycles that a woman has, the more chances there are that a tiny mistake could happen and cause cancer to start. Unlike certain other types of cancer, for ovarian cancer there is not one main, obvious, external risk factor such as smoking, sun exposure, alcohol or a virus or bacterium.

Lawyers started many lawsuits (court cases) in the United States against the drug company Johnson & Johnson (J&J). The lawyers said that some women who put Johnson & Johnson's talcum powder (baby powder) on the genital area got ovarian cancer because of the powder. Although the scientific studies for these claims may have been weak, juries have awarded women hundreds of millions of dollars. In April, 2023, Johnson & Johnson set aside nearly $9 billion US to pay women or their family members who said its baby power caused ovarian cancer.[12]

The risk of having ovarian cancer increases with age and decreases with pregnancy. It is more common in white women than in black women.[13] There is strong evidence that being tall, or being overweight or obese increases the risk of ovarian cancer.[11] Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death for females. The rate of ovarian cancer deaths has fallen by 40% since 1975. Most of this change has happened since the mid-2000s.[13] The improvement is because this type of cancer is slowly becoming less common, and because doctors have learned more about the disease and have better treatments such as better drugs available.

It is normal for cells in the body to divide to produce new cells. However, sometimes a cell is abnormal. Doctors say it has a mutation. That means it is damaged in some way or made imperfectly (copied or made wrong.) This does not happen often, but if it does, the bad cells may be able divide and make more and more damaged or imperfect cells. The problem with the cells may be that they reproduce too quickly so there are too many of them. These cells may form tumors, which are groups of damaged or incorrect cells. The problem can get worse if these cells spread or go into other parts of the body.[14] A type of cancer that spreads is called an invasive cancer. Common areas to which the cancer may spread include the lining of the abdomen, lymph nodes, lungs, and liver.[15] Only 20 percent of ovarian cancers are found before it spreads beyond the ovaries.[16]

When ovarian cancer starts, there may be no symptoms (signs that there is something wrong.)[1] Symptoms may be noticed more as the cancer progresses.[1] For ovarian cancer, the signs may be bloating (feeling swollen with fluid or gas), vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, back pain, abdominal swelling, constipation, a frequent need to urinate, feeling tired, and loss of appetite (not feeling hungry.)[1] Since most of those symptoms can be caused by many different and more common problems, ovarian cancer is usually not the first thing people think of as the cause. It is difficult for anyone, even a doctor who knows a lot about this type of cancer, to tell from the symptoms if the problem is ovarian cancer. A doctor who knows a lot about finding and treating ovarian cancer is called a gynecologic oncologist. A gynecologic oncologist usually has done seven more years of extra study and training after becoming a doctor.

The risk of ovarian cancer increases with age. Most cases of ovarian cancer develop after menopause[17] but it can happen at any age. It is also more common in women who have ovulated (released an egg from one of the ovaries, which usually happens about two weeks before the start of the menstrual period) more times over their lifetime.[18] This includes those who have never had children, those who began ovulation at a younger age and those who reach menopause at an older age. Other things that increase the risk include taking hormone drugs after menopause, fertility drugs, and obesity.[4][6] High consumption of total, saturated, and trans-fats increases ovarian cancer risk (the chance of getting it.)[19] A 2006 study involving 13,281 women found the greatest risks among foods were for meat and cheese. Eating meat once a week rather than not at all more than doubled the risk for a common type of ovarian cancer occurring after menopause. Eating cheese twice a week rather than once a week also doubled the risk.[20] Both meat and cheese are high in saturated fat, so these findings suggest that women follow the general advice to not eat foods that are high in fat, especially animal fats which are usually saturated fats. Other studies have found similar results.[21] A 2002 study said the data "suggest that a diet rich in fresh vegetables and fruits, but less animal fat, salted vegetables, fried, cured and smoked food, contribute to a lower risk of ovarian cancer."[22] A 2021 review of other studies found that coffee, egg, and fat intake increase the risk of ovarian cancer.[23] (Note, however, that coffee may lower the risk of some other types of cancer.) Things that lower the risk include hormonal birth control (commonly called "the pill"), tubal ligation (a surgical type of birth control commonly known as having one's "tubes tied", in which the fallopian tubes are permanently blocked, cut, or removed), pregnancy, and breast feeding.[6] About 10% of cases are because of inherited genetic risk. That is, if a woman's relatives such as her mother or her aunts have had this cancer, there is a higher than normal chance that she will have it some day.

Ovarian cancer can also be a secondary cancer, the result of metastasis from a primary cancer (one that happened first) elsewhere in the body. About 5-30% of ovarian cancers are due to metastases.[24]

The incidence rate (the percent of women getting this cancer) fell by 1% to 2% per year from 1990 to the mid-2010s and by almost 3% per year from 2015 to 2019. This is probably due to more use of oral contraceptives (hormonal birth control often called "the pill") and less use of hormone therapy to treat symptoms of menopause.[13]

A diagnosis of ovarian cancer is confirmed through a biopsy.[1]

Treatments usually include surgery, chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy. Immunotherapy is a newer treatment which usually has fewer side effects than chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Immunotherapy is usually only used if other treatments are no longer effective. There are several FDA-approved immunotherapy treatments for ovarian cancer.[16] Surgery usually involves removing one or both of the ovaries and may also include removing one or both of the fallopian tubes, as well as other nearby tissue. Often the doctor will first remove one ovary and/or fallopian tube through a very small incision (hole cut in the skin.) Depending on the situation, additional surgery may be needed. However, even the best treatments for ovarian cancer often do not work. Compared to some other types of cancer, ovarian cancer is a very bad cancer because there usually are no early signs of it. Also, at this time, there is not a reliable way to check for it before there are signs. This means that most of the time the cancer is not found until it has reached an advanced (late) stage, meaning the problem is already very bad. Ovarian cancer metastasizes (spreads) soon after it starts, often before a doctor or nurse is able to tell that the cancer has started. Once a cancer has started spreading, surgery usually cannot stop it from spreading more. That is why chemotherapy and radiation therapy may be recommended by the doctor after surgery.

In the case of young women who may still wish to have children, doctors may be able to remove just one ovary if the cancer is limited to the one ovary. This is called unilateral surgery rather than bilateral surgery. Risks of radiation therapy should be discussed with the medical team. Women who still wish to become pregnant should discuss the possibility of egg preservation (saving eggs for future use.)

Women who are at high risk for ovarian cancer may choose to have their ovaries removed even if they do not have ovarian cancer. For women who have already gone through menopause, this surgery may be called prophylactic postmenopausal bilateral oophorectomy. Prophylactic means something done to prevent some undesired outcome. Postmenopausal means after the woman has gone through menopause. Bilateral means both sides (since there are two ovaries.) Oophorectomy means removal of one or both ovaries. After a woman goes through menopause, she is at higher risk of various problems such as cognitive impairment, coronary artery disease, stroke and having weak bones, as well as having reduced sex drive. If the woman has already gone through menopause, removing the ovaries does not make those risks worse. On the other hand, removing the ovaries before menopause will cause menopause to occur soon after the surgery. That increases all the risks such as cognitive impairment, coronary artery disease, stroke, weak bones, and reduced sex drive. The earlier occurrence of those serious problems has to be compared to avoiding the risk of ovarian cancer, as well as breast cancer. (Women with a particular genetic variation will be at high risk of both ovarian cancer and breast cancer.) If a woman is having her uterus removed (for any reason), and is at high risk for ovarian cancer, she may be advised to consider surgical removal of her ovaries and fallopian tubes at the same time to reduce her cancer risk for both ovarian cancer and breast cancer. This is called elective prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, or elective PSO.[25] Elective means the surgery is a choice. Salpingo means the fallopian tubes. Oophorectomy means removal of one or both ovaries (in this case, both.) If the woman is close to the age when menopause usually occurs, the choice may be simple. If the woman is several or many years away from the age when menopause would naturally occur, the decision is much more difficult. For younger women having their ovaries removed, these risks can be lowered with immediate and continuous estrogen treatment until at least age 50.[26]

Ann Dunham, the mother of Barack Obama, the 44th president of the United States, died of ovarian cancer on November 7, 1995 at age 52.[27][28][29] Her ovarian cancer was a secondary cancer, which had started as uterine cancer. The worries she had about health insurance coverage for her hospital bills pushed President Obama to fight for health insurance reform, commonly known as Obamacare.

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Ebell MH, Culp MB, Radke TJ (March 2016). "A Systematic Review of Symptoms for the Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 50 (3): 384–394. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.023. PMID 26541098.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

NCI2016Onsetwas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cite error: The named reference

Zil2021was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Ovarian Cancer Prevention". NCI. 6 December 2013. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

WCR2014was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Ovarian Cancer Prevention". NCI. 20 June 2014. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

SEER2014was used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ "Ovarian Cancer Statistics | How Common is Ovarian Cancer". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Ovarian cancer statistics | World Cancer Research Fund International". WCRF International. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ↑ "Johnson & Johnson proposes nearly $9B US settlement for talc product claims". CBC. April 5, 2023.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Ovarian Cancer Statistics | How Common is Ovarian Cancer". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ↑ "Defining Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ↑ Ruddon RW (2007). Cancer Biology (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-19-517543-1. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Immunotherapy for Ovarian Cancer". Cancer Research Institute. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ↑ "Ovarian Cancer Risk Factors". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ↑ Armstrong DK (2020). "189. Gynaecologic cancers: ovarian cancer". In Goldman L, Schafer AI (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 1 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 1332–1335. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1.

- ↑ Qiu W, Lu H, Qi Y, Wang X (June 2016). "Dietary fat intake and ovarian cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies". Oncotarget. 7 (24): 37390–37406. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.8940. PMC 5095084. PMID 27119509.

- ↑ "Dietary Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer: The Adventist Health Study (United States) - McMaster Experts". experts.mcmaster.ca. Archived from the original on 2024-04-15. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ↑ "Ovarian cancer and diet: Impact, what to eat, and more". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2024-03-24.

- ↑ Zhang, M (March 4, 2002). "Diet and ovarian cancer risk: a case–control study in China".

- ↑ Tanha K, Mottaghi A, Nojomi M, Moradi M, Rajabzadeh R, Lotfi S, Janani L (November 2021). "Investigation on factors associated with ovarian cancer: an umbrella review of systematic review and meta-analyses". Journal of Ovarian Research. 14 (1): 153. doi:10.1186/s13048-021-00911-z. PMC 8582179. PMID 34758846.

- ↑ Lee SJ, Bae JH, Lee AW, Tong SY, Park YG, Park JS (February 2009). "Clinical characteristics of metastatic tumors to the ovaries". Journal of Korean Medical Science. 24 (1): 114–119. doi:10.3346/jkms.2009.24.1.114. PMC 2650975. PMID 19270823.

- ↑ Batulan, Zarah; Maarouf, Nadia; Shrivastava, Vipul; O’Brien, Edward (2018-04-27). "Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy & surgical menopause for inherited risks of cancer: the need to identify biomarkers to assess the theoretical risk of premature coronary artery disease". Women's Midlife Health. 4 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s40695-018-0037-y. ISSN 2054-2690. PMC 6297996. PMID 30766717.

- ↑ Erekson, Elisabeth A. (January 2013). "Oophorectomy: the debate between ovarian conservation and elective oophorectomy". Menopause. 20 (1): 110–114. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31825a27ab. PMC 3514564. PMID 22929033.

- ↑ "Obituaries: Stanley Ann Dunham". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. November 14, 1995. p. C12. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Obituaries: Stanley Ann Dunham". The Honolulu Advertiser. November 17, 1995. p. D6. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

freespiritwas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page).