Rotifer

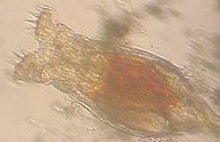

The rotifers are a phylum of tiny animals which are common in freshwater environments, such as ponds and puddles.[1] Some rotifers are free swimming, others move by inching along, and some are fixed.[2] A few species live in colonies.[3][4]

| Rotifera | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Subkingdom: | |

| Superphylum: | |

| Phylum: | Rotifera Cuvier, 1798

|

| Classes | |

|

Monogononta, Bdelloidea, Seisonidea | |

History and taxonomy

changeRotifers were first described when early microscopes became available, around 1700AD.[5] They are an important part of the freshwater zooplankton. Also, many species help decompose organic matter in soil. Rotifers eat fish waste, dead bacteria, and algae. They eat particles up to 10 micrometres in size. A rotifer filters 100,000 times its own volume of water per hour. They are used in fish tanks to help clean the water, to prevent clouds of waste matter.

About 2200 species of rotifers have been described. They are placed in the phylum Rotifera. This phylum is subdivided into three classes, Monogononta, Bdelloidea, and Seisonidea. The largest group is the Monogononta, with about 1500 species, followed by the Bdelloidea, with about 350 species.[6] There are only two known species of Seisonidea.[7][8]

Fossils of the species Habrotrocha angusticollis have been found in 6000 year old Pleistocene peat deposits.[9] The oldest known fossil rotifers have been found in Eocene Dominican amber.[10]

Appearance

changeThe front has a ring of cilia circling the mouth. This gave the rotifers their old name of "wheel animalules". There is a protective lorica round its body, and a foot. Inside the lorica are the usual organs in miniturised form: a brain, an eye-spot, jaws, stomach, kidneys, urinary bladder.

Rotifers have a number of unusual features. Biologists suppose that these peculiarities are adaptations to their small size and the transient (fast changing) nature of its habitats.

Resisting drought

changeRotifers are specialists at living in habitats where water dries up regularly.

The Monogononta, which have males, produce fertilised 'resting eggs' which can resist desiccation (drought) for long periods.[11]

The Bdelloids, who have no males, contract into an inert form and lose almost all body water, a process known as cryptobiosis. Bdelloids can also survive the dry state for long periods: the longest well-documented dormancy is nine years. After they have dried, they may be revived by adding water. In this, and several other ways, they are a unique group of animals.[12]

Cell number

changeRotifers are hatched with a standard number of cell nuclei, exactly the same number for every rotifer in a species. This is called eutely. No cell division whatsoever takes place during adult life.[13] Not only that, but the number of nuclei in each tissue is constant. Furthermore, most of the nuclei do not have cell walls: rotifer tissue is largely or wholly a syncytium.[14]

Resisting radiation

changeThe absence of cell division is probably one reason they are extraordinarily resistant to ionising radiation. Also, repairing DNA is one of the things they are known to do after desiccation.[15]

Bdelloid rotifers

changeParthenogenesis

changeIn one of the classes, the freshwater Bdelloid rotifers, no males have ever been seen. It is the largest group of wholly parthenogenetic species in the Animalia.

The females in this group produce eggs by parthenogenesis (virgin birth). In some species these eggs develop into small juveniles before they are released from their parent. The offspring are clones of their mother.

Cytological and molecular genetic studies show that bdelloids evolved from a common ancestor which lost sexual recombination (meiosis and fertilisation) about 100 million years ago.[16] Research has also been done on the implications of parthenogenesis for speciation.[17]

Genetics

changeBdelloid rotifer genomes contain two or more non-identical copies of each gene. This suggests their asexual reproduction is of long standing.[18] For example, there are four copies of gene hsp82. Each is different and on a different chromosome. This cannot be explaned by normal gene duplication, which produces two or more near-identical genes next to each other. By contrast, in a monogont rotifer, most genes were single-copy.[19]

There are genes in bdelloid rotifers that seem to have come from bacteria, fungi, and plants. This suggests they arrived by horizontal gene transfer (HGT). The capture and use of exogenous (~foreign) genes seems to be important in bdelloid evolution.[20][21] The team led by Matthew S. Meselson at Harvard University showed that, despite the lack of sexual reproduction, bdelloid rotifers do engage in genetic (DNA) transfer within a species or clade. The method used is not known at present. Bdelloid rotifers currently hold the 'record' for HGT in animals with ~8% of their genes from bacterial origins.[22]

The Acanthocephala

changeThe Acanthocephala, a group of parasitic worms previously considered to be a separate phylum, have been shown to be modified rotifers. The exact relationship to the normal, freeliving, members of the phylum is not resolved.[14]

Rotifer web sites

changeReferences

change- ↑ There are a few saltwater species.

- ↑ They live inside tubes or gelatinous holdfasts that are attached to a substrate

- ↑ Clément P. and Wurdak E. 1991. Rotifera. In: Harrison F.W. and E.E. Ruppert eds. Microscopic Anatomy of Invertebrates vol 4. pages 219-297. Wiley-Liss, New York.

- ↑ Nogrady, Thomas, Wallace R.L. & Snell T.W. 1993. Rotifera, vol. 1: biology, ecology and systematics. The Hague: SPB Academic Publishing.

- ↑ Harmer, Sidney Frederic and Shipley, Arthur Everett (1896). The Cambridge Natural History. Macmillan, London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ricci, Claudia & Melone, Guilio 2000. Key to the identification of the genera of bdelloid rotifers. Hydrobiologia 418: 73-80.

- ↑ Hudson C.T. and P.H. Gosse. 1889. The Rotifera: or, wheel-animalcules. Longmans Green, London.

- ↑ Baqai, Aisha; Guruswamy, Vivek; Liu, Janie; and Rizki, Gizem (2000). "Introduction to the Rotifera". University of California Museum of Paleontology.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Warner B.G. et al. 1988. Holocene fossil Habrotrocha angusticollis (Bdelloidea: Rotifera) in North America. Journal of Paleolimnology 1: 141-147.

- ↑ Waggoner B.M. & Poinar G.O. Jr. 1993. Fossil habrotrochid rotifers in Dominican amber. Experientia (Basel) 49: 354-357.

- ↑ Örstan A. 1995. Desiccation survival of the eggs of the rotifer Adineta vaga (Davis 1873). Hydrobiologia 313/314:373-375

- ↑ Kirk, Kevin L. et al. 1999. Physiological responses to variable environments: storage and respiration in starving rotifers. Freshwater Biology 42 637-644.

- ↑ Their eggs are already present in the adult rotifer.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Shimek, Ronald 2006. "Nano-Animals, Part I: Rotifers". Reefkeeping.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ E. Gladyshev and M. Meselson. Extreme resistance of bdelloid rotifers to ionizing radiation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 10.1073/pnas.0800966105 (published online 3/24/08)

- ↑ "Welch, Mark". Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ↑ Fontaneto D. et al. 2007. Independently evolving species in asexual Bdelloid rotifers. PLoS [1] Archived 2009-08-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Welch J.L.M. Welch D.B.M and Meselson M. 2004. Cytogenic evidence for asexual evolution of bdelloid rotifers. PNAS 101 pp1618–1621

- ↑ Suga K et al. Analysis of expressed sequence tags of the cyclically parthenogenetic rotifer Brachionus plicatilis. PLOS One [2]

- ↑ Gladyshev E.A. Meselson M. & Arkhipova I.R. 2008. Massive horizontal gene transfer in Bdelloid rotifers. Science 320, pp1210 - 1213

- ↑ Arkhipova I.R. and Meselson M. 2005. Diverse DNA transposons in rotifers of the class Bdelloidea. PNAS 102: 11781-11786

- ↑ Traci Watson (2012). "Bdelloids surviving on borrowed DNA". Science/AAAS News.