Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

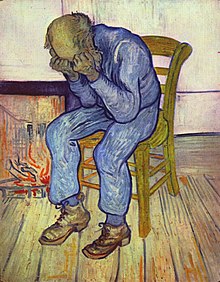

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are a group of medications. They are usually called SSRIs. They are used to treat depression, anxiety disorders, and some other problems.

In many countries, SSRIs are prescribed more often than any other type of antidepressant.[1]

Examples of common SSRIs are fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), citalopram (Celena), and escitalopram (Lexapro).

Medical uses

changeSSRIs are mainly used to treat:[1]

- Major depressive disorder

- Anxiety disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); panic disorder; and generalized anxiety disorder

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Eating disorders

- Chronic pain

Depression

changeAntidepressants like SSRIs are a first-choice treatment for people with very bad depression. When a person's depression is not as bad, but counseling has not helped them, antidepressants can help.[2]

Scientists do not agree on whether SSRIs work for mild depression that does not last very long.[2]

Anxiety disorders

changeSSRIs work well for generalized anxiety disorder. They help decrease people's anxiety. This can help them participate in counseling to learn how to deal with their anxiety.[3]

SSRIs also work well for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). They are the first-choice treatment for people with very bad OCD. Like with depression and generalized anxiety disorder, SSRIs are not a cure; people need to participate in counseling and other treatments too. However, people with OCD who took an SSRI are about twice as likely to do well in treatment than people not taking an SSRI.[4][5]

Fluoxetine (Prozac) and paroxetine (Paxil) are the only medications the United States Food and Drug Administration has approved for treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Medications alone usually will not cure PTSD; they need to be combined with counseling.[6][7][8] Except for Prozac and Paxil, most other SSRIs do not seem to help PTSD.[9]

Eating disorders

changeWhen a person starts to get treatment for bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder, SSRIs can be a helpful first step.[10] Over short periods of time, they can decrease some of the symptoms of these eating disorders. For example, for a short while, people taking SSRIs do less binge eating.[11] However, SSRIs only seem to help for a short period of time.[10]

SSRIs do not seem to help anorexia nervosa.[12] However, if a person with anorexia also has depression, anxiety, or OCD, SSRIs could help treat those problems.[11]

Chronic pain

changeResearch shows that two SSRIs can help treat chronic pain. These SSRIs are paroxetine (Paxil) and citalopram (Celexa). Other SSRIs, like fluoxetine (Prozac), do not help chronic pain.[13]

Another group of antidepressants, called tricyclic antidepressants, treat chronic pain better than SSRIs do. However, tricyclic antidepressants have many more side effects than SSRIs do. Because of this, some doctors prescribe paroxetine or citalopram for chronic pain, because the side effects are not as bad.[13]

How they work

changeSerotonin is an important chemical in the human body. It exists in different parts of the body. In the brain, it helps control a person's mood, appetite, and sleep.[14]

Many researchers think low levels of serotonin in the brain can help cause depression.[14] If a person's brain does not have enough serotonin, the serotonin cannot do its job of controlling their mood. This can make the person depressed. (It can also cause other symptoms of depression, like not having any appetite, not being able to sleep, or sleeping too much - because serotonin controls appetite and sleep too.)[14]

SSRIs increase the amount of serotonin that the brain can use.[14] Researchers think that in depressed people, this brings the amounts of serotonin in their brains back to normal.

However, depression is complicated. So are the other problems SSRIs treat, like anxiety disorders. There is no one cause for these disorders. They are usually caused by a mixture of things. This is why SSRIs are not a cure. Most people also need counseling to help treat the other causes of their depression, anxiety, or other problems.[6][7][8]

Adverse effects

changeEach SSRI has its own possible adverse effects (side effects). It is important to remember that every medication has many possible side effects. This does not mean that everyone who takes the medication will have side effects. It only means that some people who take these medications have these symptoms.

Here are some examples of adverse effects that SSRIs can cause.

Suicide risk

changeTaking SSRIs makes children and young adults more likely to think about suicide and try to kill themselves.[15][16][17] This is true for young adults up to age 24.[18]

In 2004, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) looked at clinical trials on children with major depressive disorder. They found that children taking SSRIs had:[19]

- An 80% higher risk of "possible suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior".

- About a 130% greater risk of agitation (getting angry and upset easily) and hostility (acting angry towards other people).

In both the United States and the United Kingdom, only three SSRIs are approved to treat children:

- Fluoxetine (Prozac), to treat children with depression.[20][18]

- Sertraline (Zoloft) and fluvoxamine (Luvox), for children with OCD.[21][18]

Scientists do not agree on whether SSRIs make adults more likely to think about suicide or try to kill themselves. The FDA says that people over age 24 are not more likely to think about suicide when they take SSRIs.[18]

Sexual problems

changeSSRIs often cause sexual problems.[22] These problems include erectile dysfunction, not being able to have an orgasm, not wanting to have sex, and not enjoying sex.[23]

Sexual problems are one of the most common reasons why people stop taking SSRIs.[24]

Bleeding

changeWhen a person takes SSRIs along with anticoagulant (blood-thinning) medications, they are a little more likely to have bleeding problems.[25][26][27][28] For example, the person is more likely to have bleeding in their digestive system (gastrointestinal tract), or to bleed after they have surgery.[25] Bleeding problems are most likely in people who:[29][30]

- Are on blood-thinning medications, like warfarin (Coumadin); AND

- Are on medications that stop blood cells called platelets from forming blood clots, like aspirin; AND

- Are taking a type of painkiller called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), like ibuprofen; AND

- Have problems with their liver, like liver disease or liver failure.

Other problems

changeMost SSRIs can also make a person:

Stopping suddenly

changeIf a person stops taking SSRIs suddenly, they can get side effects that are painful or distressing. The medical name of these side effects is serotonin discontinuation syndrome. This can cause:[37][38]

- Nausea

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Pain in the whole body

- Strange feelings on the skin

- Trouble sleeping

- Feeling like the body is being shocked with electricity

A person and their doctor should come up with a plan for how to stop taking an SSRI. If possible, the person should slowly decrease the amount of medication they are taking, bit by bit, over a few weeks.[37]

Overdose

changeIf a person takes too much SSRI medication at once (overdose), they can poison themselves or even die.[37][39][40]

SSRI overdoses can cause:[41][42]

- Serotonin syndrome

- Coma

- Seizures

- Poisoning of the heart

Drug interactions

changeIt is not safe to take some drugs with SSRIs. Taking these drugs with SSRIs can cause serotonin syndrome. Here are some examples of drugs that cannot be taken with SSRIs:[43][44]

- Some other medicines for depression and anxiety:

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- Tricyclic antidepressants

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Lithium

- Buspirone (Buspar)

- Mirtazapine (Remeron)

- Some pain medications:

- Pethidine/meperidine (Demerol)

- Tramadol (Ultram)

- Other medications:

- Dextromethorphan, an over-the-counter cough medicine

- St. John's Wort, an herb that some people use to treat depression

- MDMA (Ecstasy), an illegal drug

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Preskorn, Sheldon H.; Ross, Ruth; Stanga, Christine Y. (2004). "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors". In Sheldon H. Preskorn; Hohn P. Feighner; Christina Y. Stanga; Ruth Ross (eds.). Antidepressants: Past, Present and Future. Berlin: Springer. pp. 241–62. ISBN 978-3-540-43054-4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Depression in Adults: Recognition and Management". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. RCPsych Publications. 2009.

- ↑ Kapczinski F; Lima MS (2003). Kapczinski, Flavio FK (ed.). "Antidepressants for generalized anxiety disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003592. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003592. PMID 12804478.

- ↑ Arroll B; Elley CR (2009). Arroll, Bruce (ed.). "Antidepressants versus placebo for depression in primary care". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (3): CD007954. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007954. PMC 10576545. PMID 19588448.

- ↑ Busko, Marlene (February 28, 2008). "Review Finds SSRIs Modestly Effective in Short-Term Treatment of OCD". Medscape. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hetrick SE; Purcell R (July 7, 2010). "Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological therapies for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD007316. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007316.pub2. PMID 20614457.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Berger W; Mendlowicz MV (2009). "Pharmacologic alternatives to antidepressants in posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 33 (2): 169–180. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.12.004. ISSN 0278-5846. PMC 2720612. PMID 19141307.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bandelow B; Zohar J (2008). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry: The Official Journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. 9 (4): 248–312. doi:10.1080/15622970802465807. ISSN 1562-2975. PMID 18949648. S2CID 39027026.

- ↑ Hoskins M; Pearce J (2015). "Pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Psychiatry. 206 (2): 93–100. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.148551. PMID 25644881.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Eating Disorders in Over 8s: Management" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. January 2004. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders". National Guideline Clearinghouse. United States Department of Health and Human Resources. 2011. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ Flament MF; Bissada H (2012). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of eating disorders". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology / Official Scientific Journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum (CINP). 15 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000381. PMID 21414249. S2CID 24864203.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sansone RA; Sansone LA 2008 (2008). "Pain, Pain, Go Away: Antidepressants and Pain Management". Psychiatry. 5 (12): 16–19. doi:10.4230/LIPIcs.FSTTCS.2015.69. PMC 2729622. PMID 19724772. S2CID 2729622.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Artigas F (2013). "Serotonin Receptors Involved in Antidepressant Effects". Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 137 (1). Elsevier: 119–131. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.09.006. hdl:10261/88634. PMID 23022360.

- ↑ Laughren, Thomas (November 16, 2006). "Results: Estimates of Suicide Risk Associated with Antidepressant Treatment" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). United States Food and Drug Administration. pp. 33–34. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ Levenson, Mark; Holland, Chris (December 13, 2006). "Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation". FDA.gov. United States Food and Drug Association. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ Olfson M; Marcus SC (2006). "Antidepressant drug therapy and suicide in severely depressed children and adults: A case-control study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (8): 865–72. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.865. PMID 16894062.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 "Revisions to Product Labeling" (PDF). FDA.gov. United States Federal Drug Administration. 2007. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ↑ Hammad TA (August 16, 2004). "Review and evaluation of clinical data. Relationship between psychiatric drugs and pediatric suicidal behavior" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 42, 115. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Guidance: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): use and safety". Gov.UK. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency of the United Kingdom. December 18, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents including a summary of available safety and efficacy data". Gov.UK. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency of the United Kingdom. September 29, 2005. Archived from the original on June 12, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ Taylor MJ; Rudkin L (2013). "Strategies for managing sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressant medication". The Cochrane Database of Rystematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD003382. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003382.pub3. PMID 23728643.

- ↑ Bahrick A 2008 (2008). "Persistence of Sexual Dysfunction Side Effects after Discontinuation of Antidepressant Medications: Emerging Evidence". The Open Psychology Journal. 1: 42–50. doi:10.2174/1874350100801010042.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kennedy SH; Rizvi S (2009). "Sexual Dysfunction, Depression, and the Impact of Antidepressants". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 29 (2): 157–64. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e31819c76e9. PMID 19512977. S2CID 739831.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Weinrieb RM; Auriacombe M (2005). "Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and the risk of bleeding". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 4 (2): 337–44. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.2.337. PMID 15794724. S2CID 46551382.

- ↑ Taylor, D; Carol, P; Shitij, K (2012). The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780470979693.

- ↑ Andrade C; Sandarsh S (2010). "Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants and Abnormal Bleeding: A Review for Clinicians and a Reconsideration of Mechanisms". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (12): 1565–1575. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05786blu. PMID 21190637.

- ↑ de Abajo FJ; García-Rodríguez LA (2008). "Risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine therapy: interaction with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and effect of acid-suppressing agents". Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (7): 795–803. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.795. PMID 18606952. S2CID 6822650.

- ↑ Andrade C; Sandarsh S (2010). "Serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and abnormal bleeding: a review for clinicians and a reconsideration of mechanisms". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (12): 1565–75. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05786blu. PMID 21190637.

- ↑ de Abajo FJ (2011). "Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on platelet function: mechanisms, clinical outcomes and implications for use in elderly patients". Drugs & Aging. 28 (5): 345–67. doi:10.2165/11589340-000000000-00000. PMID 21542658. S2CID 116561324.

- ↑ Wu Q; Bencaz AF (2012). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies". Osteoporosis International : A Journal Established as Result of Cooperation Between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 23 (1): 365–75. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1778-8. PMID 21904950. S2CID 37138272.

- ↑ Stahl SM; Lonnen AJ (2011). "The Mechanism of Drug-induced Akathsia". CNS Spectrums. 16 (1): 7–10. doi:10.1017/S1092852912000107. PMID 21406165. S2CID 43399486.

- ↑ Lane RM 1998 (1998). "SSRI-induced extrapyramidal side-effects and akathisia: implications for treatment". Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 12 (2): 192–214. doi:10.1177/026988119801200212. PMID 9694033. S2CID 20944428.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Koliscak LP; Makela EH (2009). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced akathisia". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA. 49 (2): e28–36, quiz e37–8. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2009.08083. PMID 19289334.

- ↑ Leo RJ (1996). "Movement disorders associated with the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 57 (10): 449–54. doi:10.4088/JCP.v57n1002. PMID 8909330.

- ↑ Dryden-Edwards, Roxanne (March 31, 2015). "SSRIs and Depression: SSRI Drug Side Effects". EMedicineHealth.com. WebMD, LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder" (PDF) (3rd ed.). American Psychiatric Association. pp. 36–39. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ Renoir T (2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant treatment discontinuation syndrome: A review of the clinical evidence and the possible mechanisms involved". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 4: 45. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00045. PMC 3627130. PMID 23596418.

- ↑ Borys DJ; Setzer SC (1992). "Acute fluoxetine overdose: a report of 234 cases". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 10 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(92)90041-U. PMID 1586402.

- ↑ Oström M; Ericsson A (1996). "Fatal overdose with citalopram". Lancet. 348 (9023): 339–40. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64513-8. PMID 8709713. S2CID 5287418.

- ↑ Sporer KA (1995). "The serotonin syndrome. Implicated drugs, pathophysiology and management". Drug Safety : An International Journal of Medical Toxicology and Drug Experience. 13 (2): 94–104. doi:10.2165/00002018-199513020-00004. PMID 7576268. S2CID 19809259.

- ↑ Isbister GK; Bowe SJ (2004). "Relative toxicity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in overdose". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 42 (3): 277–85. doi:10.1081/CLT-120037428. PMID 15362595. S2CID 43121327.

- ↑ Ener RA; Meglathery SB\ (2003). "Serotonin Syndrome and Other Serotonergic Disorders". Pain Medicine. 4 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03005.x. PMID 12873279. S2CID 45762494.

- ↑ Boyer EW; Shannon M (2005). "The serotonin syndrome" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–1120. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2016-02-27.