The Nutcracker

The Nutcracker is a classical ballet in two acts. It is based on E.T.A. Hoffmann's 1816 fairy tale The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. It tells the story of a little girl who goes to the Land of Sweets on Christmas Eve. Ivan Vsevolozhsky and Marius Petipa adapted Hoffmann's story for the ballet. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote the music. Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov designed the dances. The Nutcracker was first performed at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, on 18 December 1892 to a modest success and rarely seen the next years.

| The Nutcracker | |

|---|---|

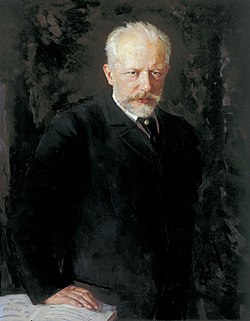

Tchaikovsky in 1892 | |

| Choreographed by | Marius Petipa Lev Ivanov |

| Composed by | Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky |

| Libretto by | Ivan Vsevolozhsky Marius Petipa |

| Based on | E.T.A. Hoffmann's "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King" |

| Date of premiere | 18 December 1892 |

| Place of premiere | Mariinsky Theatre St. Petersburg |

| Original ballet company | Mariinsky Ballet |

| Characters | Clara Drosselmeyer Nutcracker Prince Mouse King Sugar Plum Fairy |

| Designs by | M. I. Botcharov K. M. Ivanov Ivan Vsevolozhsky |

| Setting | Act 1: Christmas Eve in 19th century Germany Act 2: The Land of Sweets |

| Genre | Fairy tale |

| Type | Classical ballet |

In 1940, Walt Disney used some of the Nutcracker music in his animated movie Fantasia, which led to an interest in the ballet. Interest grew when George Balanchine's The Nutcracker was televised in the late 1950s. The ballet has been performed in many different places since then. Before the first performance, Tchaikovsky took some numbers from the ballet to form the Nutcracker Suite. This work was a great success on the concert stage, and is still played today.

Origin change

The origin of The Nutcracker has its roots in the great success of The Sleeping Beauty ballet. This ballet was staged at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1890. It was the work of the director of the Imperial Theatres in St. Petersburg, Ivan Vsevolozhsky; the composer, Tchaikovsky; and the choreographer, Marius Petipa. Vsevolozsky thought another ballet based on a children's story would be just as successful as The Sleeping Beauty.[1]

He picked Hoffmann's 1816 fairy tale "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King" as the subject for the new ballet. This story was loved by Russians. He wrote an adaptation of Hoffmann's story based on the Alexandre Dumas translation. He dropped much of the original. Petipa adapted Vsevolozsky's story to the requirements of ballet. Vsevolozsky then pressured Tchaikovsky into writing the music for the ballet. Tchaikovsky did not like the adaptation of Hoffmann's story, but he agreed to write the music.[2]

Petipa designed the dances. He gave Tchaikovsky special directions about how the music was to be written. For example, he wanted a great crescendo of 48 bars as the Christmas tree rose higher and higher in Act 1. He wrote that the music for the "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" should sound like drops of water splashing in a fountain.[3]

In March 1892 the music was almost complete. Tchaikovsky took the "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy", the "Waltz of the Flowers", and other numbers from the ballet to form the 20-minute Nutcracker Suite. It was first played for the Russian Musical Society. The organization's members loved it. Nutcracker Suite is still played today.[4]

Tchaikovsky completed the music for the ballet in April 1892. Rehearsals started in September 1892. Petipa fell ill and his assistant Lev Ivanov completed the dances.[5] The ballet was first performed on 18 December 1892 at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg.[6] Tchaikovsky's one-act opera Iolanta was played before the curtain rose on The Nutcracker. The run ended in 1893 after eleven performances.[7]

Later change

In 1919, choreographer Alexander Gorsky staged a production. He cut out the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier, and gave their dances to Clara and the Nutcracker Prince. They were now played by adults instead of children. A shortened version of the ballet was first performed outside Russia in Budapest's Royal Opera House in 1927.[8]

In 1934, Vasili Vainonen, choreographer of the Kirov Ballet, staged a version of the work which was also influenced by the criticisms of the original production. He also cast adult dancers in the roles of Clara and the Prince, as Gorsky had. The Vainonen version influenced several later productions.[9] Knowledge of the choreography spread because many dancers went to the west after the Russian Revolution.

The first complete performance outside Russia took place in England in 1934.[10] It was staged by Nicholas Sergeyev at the Vic-Wells Ballet. It used a version of Petipa's original choreography. Annual performances of the ballet have been staged there since 1952.[11]

Plot change

The ballet takes place in Germany in the early 19th century. The curtain rises on a Christmas Eve party in the Silberhaus home. Guests arrive. The children get their presents, then dance about the room.

The door opens. A strange little man named Drosselmeyer comes into the room. He is a toy-maker. He is also Clara Silberhaus's godfather. He has four dancing dolls for the children and a special surprise for Clara. It is a nutcracker. She loves it, but her brother Fritz accidentally breaks it. She places the Nutcracker in her doll bed to get well.

The party ends and everyone leaves. Clara and her family go to bed. Clara creeps back to the room. She needs to be certain her Nutcracker is resting quietly. All of a sudden, mice start running about the room. The dolls, the tin soldiers, and all the other playthings come to life to fight the mice.

The Christmas tree rises higher and higher. The Nutcracker jumps out of the doll bed to fight the Mouse King. When the Nutcracker is in danger, Clara saves his life by throwing her slipper at the Mouse King. The Mouse King runs out of the room with all the other mice.

The Nutcracker becomes a human prince. Clara and the Nutcracker Prince set off through the snowy woods for the magical Land of Sweets. The beautiful Sugar Plum Fairy rules this land. She welcomes the two children then orders her subjects to dance for them. Dances about Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate are presented. Many other dances are presented. The ballet ends with everyone dancing a waltz.[12]

Structure change

- Overture

Act I: Tableau 1

- No.1 Scene (The Christmas Tree)

- No.2 March

- No.3 Children's Galop and Dance of the Parents

- No.4 Dance Scene (Arrival of Drosselmeyer)

- No.5 Scene and Grandfather Dance

- No.6 Scene (Clara and the Nutcracker)

- No.7 Scene (The Battle)

Act I: Tableau 2

- No.8 Scene (A Pine Forest in Winter)

- No.9 Waltz of the Snowflakes

Act II: Tableau 3

- No.10 Scene (The Kingdom of Sweets)

- No.11 Scene (Clara and Nutcracker Prince)

- No.12 Divertissement:

- a.Chocolate (Spanish Dance)

- b.Coffee (Arabian Dance)

- c.Tea (Chinese Dance)

- d.Trepak (Russian Dance)

- e.Dance of the Reed-Pipes

- f. Mother Gigogne and the Clowns

- No.13 Waltz of the Flowers

- No.14 Pas de Deux (Sugar Plum Fairy and Prince Coqueluche)

- No.15 Final Waltz and Apotheosis

Reception change

Criticism of the ballet was mixed. A portion thought of it to be a noble composition, with exemplary themes and emotion, however many thought otherwise.[7] Russian balletomanes liked expert adult dancers and the large cast of children was critically attacked. One person complained that the ballet was "produced with children for children."[13] Even the adult dancers came under fire. One person, for example, thought the dancer playing the doll in Act 1 was "nice" while another person thought she was "insipid".[14]

One critic complained that the ballet was in bad taste because characters in Act 2 looked like food from a pastry shop. Another complained that Ivanov's "Waltz of the Snowflakes" was taken from ballets by Petipa.[15] Tchaikovsky however thought that the staging was very beautiful, so much so that his eyes grew tired looking at it.[16]

Some people were surprised that Tchaikovsky had anything to do with the ballet. They thought The Nutcracker was foolish. They were embarrassed that the great composer had had a hand in it.[17] On the first night however, Czar Alexander III called Tchaikovsky before him in the royal box to congratulate him on the music.[16]

The newspapers were divided on the ballet's value. The St. Petersburg Gazette wrote "this ballet is the most tedious thing ever seen ... a long way from what ballet music should be." The St. Petersburg News-sheet wrote, "It is hard to say which number is the greatest, for everything from start to finish is beautiful." The New Age wrote that Tchaikovsky's orchestral writing was the work of genius.[6] A ballet lover thought The Nutcracker was the greatest of the three ballets Tchaikovsky had written.[15]

Post-Premier change

The ballet's initial run ended in January 1893. When the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917, many ballet dancers were put out of work. They went to Europe. They talked to their new friends in Europe about The Nutcracker. Some selections were performed here and there.

In 1940 Walt Disney used some of the music in his movie Fantasia.[18] In 1944 the Nutcracker was staged at the San Francisco Ballet by William Christensen,[19] the 'very first full-length' on Christmas Eve.

Christensen (1902-2001) was called the grandfather of American Ballet. He was born in Brigham City, Utah. He had established the San Francisco Ballet in 1938. Later he founded the ballet department to the University of Utah in 1951, the first of its kind, and Ballet West in 1963.

Christensen’s creation had its 75th Anniversary during the 2019-2020 season. In 1954 George Balanchine staged The Nutcracker in New York City. People liked it. When it was aired on television in 1957 and 1958, the ballet became more famous than ever. Balanchine's television Nutcracker had enough fun in it for people who had not seen a ballet, and enough dancing in it to please the ballet lovers who watched it. In the 1960s small ballet companies started producing The Nutcracker because it could make money and, in doing so, keep the company in business.[18]

Modern times change

Today, The Nutcracker has been staged and seen by many people all over the world. Jennifer Fisher points out that it is "the most popular and most often [staged] ballet in the world."[20] In North America, it is a yearly event in many places. Parents and children take part in staging the ballet and dancing in it. Trained ballerinas dance side by side with children who are only learning to dance. Parents work on costumes and sets. Local celebrities take small walk-on parts.[21]

There have been many adaptations of the ballet over the years. In the United States, for example, there are hula, tap dance, reggae, wheelchair, dance-along, ice, and drag versions.[21] In Canada, there have been hockey adaptations.[22] Products such as Nutcracker dolls, soaps, foods, and clothing are sold in theatres before the show.[23]

Ballet lovers question the present day dumbing-down (oversimplification) of The Nutcracker to make it accessible to the masses. The reasons the ballet was originally disliked in Russia (the many child dancers, the uneven story) seem to be the reasons the ballet has become such a great success in North America. Americans like seeing their children on stage and the story is very much like the rags-to-riches stories Americans love.[23] Some people though complain about the stereotypes of children in Act 1 (boys are naughty, girls are nice) and also about the stereotypes of Arabians and the Chinese in Act 2.[24]

Music change

Instrumentation change

Tchaikovsky wrote The Nutcracker for an orchestra of strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion. To this orchestra he added a celesta for the "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" in Act 2 and children's instruments—drums, trumpets, cymbals, bird calls, whistles, and a rattle—for the Christmas party in Act 1. The instruments were specially ordered and tuned to Tchaikovsky's orders. The rattle is heard in the orchestra pit when Fritz cracks nuts in Act 1, and the other instruments are heard when the boys make a lot of noise while Clara comforts the broken Nutcracker.

Tchaikovsky hoped that the children would play the instruments on the stage, but they had difficulty keeping together with the orchestra. Because of the difficulty the children had, Tchaikovsky made the decision that they could play freely. He did not ask them to keep with the written music. After the first night, Tchaikovsky sent his thanks and baskets of sweets to the children of the Imperial Ballet School.[25]

Sugar Plum Fairy change

The Sugar Plum Fairy is a character in The Nutcracker. The Sugar Plum Fairy only dances in Act 2 of the ballet. Clara falls asleep, and the second act could be seen as Clara's dream. Roland John Wiley however, thinks that the second act is a reality shaped by Drosselmeyer.[26] The Sugar Plum Fairy is the ruler of the Land of Sweets. She welcomes the Nutcracker Prince and his love Clara to her land and orders the festivities. The character is danced by a prima ballerina (principal dancer), though she has little dancing to do. She is joined by a male dancer for a pas de deux near the end of the ballet. Her number in this pas de deux is called "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy".

Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy change

The "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" is one of the most famous numbers in The Nutcracker. It was written for the celesta. This instrument was new at the time the dance was written. It looks like a small piano, but it sounds like bells. Tchaikovsky discovered the celesta in Paris in 1891 while making a journey to the United States. His publisher purchased one and promised to keep the purchase a secret. Tchaikovsky did not want Rimsky-Korsakov or Glazunov to "get wind of it and ... use it for unusual (different, strange) effects before me."[27][28] Petipa wanted the Sugar Plum Fairy's music to sound like drops of water splashing in a fountain. Tchaikovsky thought the celesta was the instrument to do this.[29] The original steps for the dance are unknown.[30] Antonietta Dell'Era was the first to dance the part of the Sugar Plum Fairy.[7][16] The character has very little dancing to do so Dell'Era put a gavotte by Alphonse Czibulka into the ballet. She then had something more to do.[31]

Critical opinion change

In his biography about Tchaikovsky John Warrack points out that the ballet's greatest weakness is its story. It did not permit Tchaikovsky to musically develop the ballet in the manner of Swan Lake or The Sleeping Beauty. What few symphonic passages exist in the ballet (mostly in Act 1) are not the best Tchaikovsky wrote. Warrack thinks that the "essential nature" of the ballet is found in the separate numbers. Tchaikovsky knew this when he put together the Nutcracker Suite to promote the complete ballet. Because the story was so weak and did not permit symphonic development, Tchaikovsky indulged his taste for "prettiness" in the separate numbers. This is what makes The Nutcracker, according to Warrack, an "entertainment of genius".[32]

In the biography Tchaikovsky, writer David Brown points out that Tchaikovsky was not happy with The Nutcracker and complained to his friends about the difficulty of setting the tale to music. Brown asks why Tchaikovsky would ever let himself be persuaded to accept the story as the subject for a ballet. He points out that Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty were "dramatically meaty and deeply serious" while The Nutcracker was "trite ... [and] pointless." The ballet has no true climax he writes. He then asks, "What was it all about anyway? The Nutcracker is meaningless in the profoundest sense." He decides that the ballet is the "most inconsequential" of all the composer's mature works for theatre, and "its dramatic structure the least satisfactory." While Brown never gives his approval to The Nutcracker, he thinks Tchaikovsky did a remarkable job despite the "appalling limitations of the subject."[17]

Notes change

- ↑ Anderson 1979, p. 15

- ↑ Wiley 1985, pp. 193–94

- ↑ Anderson 1979, pp. 30, 34

- ↑ Anderson 1979, p. 39

- ↑ Warrack 1979, p. 58

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Warrack 1979, p. 59

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Brown 1991, p. 336

- ↑ "Ballet Talk [Powered by Invision Power Board]". Ballettalk.invisionzone.com. 26 November 2008. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ↑ Anderson 1979

- ↑ Crane, Debra & Mackrell, Judith 2000. The Oxford dictionary of dance. Oxford University Press, p351. ISBN 0-19-860106-9

- ↑ Craine, Debra (8 December 2007). "Christmas cracker". The Times. London.

- ↑ Brown 1991, pp. 337–39

- ↑ Fisher 2003, p. 14

- ↑ Wiley 1985, p. 220

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wiley 1985, p. 221

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Anderson 1979, p. 51

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Brown 1991, p. 339

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Fisher 2007, pp. 248–51

- ↑ Conyers, Claude (2011-02-23). Ballet West. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.a2092316.

- ↑ Fisher 2007, p. 246

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Fisher 2007, pp. 106–07

- ↑ Fisher 2007, p. 250

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Fisher 2007, p. 252

- ↑ Fisher 2007, pp. 253–54

- ↑ Wiley 1985, pp. 230–31

- ↑ Wiley, Roland John (1984) On Meaning in "Nutcracker" in Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research Vol. 3 No. 1 pp 3-28. JSTOR

- ↑ Brown 1991, p. 349

- ↑ Wiley 1985, pp. 228–29

- ↑ Anderson 1979, p. 38

- ↑ Wiley 1985, p. 219

- ↑ Wiley 1985, p. 204

- ↑ Warrack 1979, p. 60

References change

- Anderson, Jack (1979), The Nutcracker Ballet, New York: Gallery Books, ISBN 0-8317-6487-2

- Brown, David (1991), Tchaikovsky: the final years, 1885-1893, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., ISBN 978-0-393-33757-0

- Fisher, Jennifer (2003), Nutcracker Nation: how an Old World ballet became a Christmas tradition in the New World, New Haven and New York: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10599-1

- Fisher, Jennifer (2007), "The Nutcracker: a cultural icon", in Kant, Marion (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Ballet, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-53986-9

- Warrack, John (1979), Tchaikovsky Ballet Music, BBC Music Guides, Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 0-295-95697-6

- Wiley, Roland John (1985), Tchaikovsky's Ballets, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-816249-9

Further reading change

- Hurley, Thérèse (2007), "Opening the door to fairy-tale world: Tchaikovsky's ballet music", in Kant, Marion (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Ballet, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53986-9

- Tchaikovsky, Modeste (1906), The Life and Letters of Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky, London: John Lane

- Warrack, John (1966), Swan Lake: Tchaikovsky's "Swan Lake": true drama in dance form) (VHS (070 201-3) liner notes ed.), New York: Philips/PolyGram Records

- Wyatt, Edward (November 26, 2007), "Classic, flashy, naughty: which Nutcracker works for you?", New York Times, New York

Other websites change

Media related to The Nutcracker at Wikimedia Commons

- The Nutcracker ballet Archived 2012-03-15 at the Wayback Machine