User:This lousy T-shirt/Myrrh

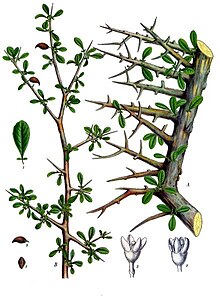

Myrrh is the dried oleo gum resin of a number of Commiphora or dhidin species of trees. The Myrrh trees are small or low thorny shrubs that grow in rocky terrain.[1] Like frankincense, it is produced by the tree as a reaction to a purposeful wound through the bark and into the sapwood. The trees are bled in this way on a regular basis. When at the tree, myrrh is waxy and brittle, but after the resin is collected into large bales it becomes a dry, hard and glossy substance that can be clear or opaque, and vary in colour depending on aging from yellowish to almost black, with white streaks.[2] The principal species is Commiphora myrrha, which is native to Yemen, Somalia, and the eastern parts of Ethiopia. Another primary species is C. momol.[3] The related Commiphora gileadensis, native to Eastern Mediterranean and particularly the Arabian Peninsula,[4] is the biblically referenced balm of Gilead. Several other species yield bdellium, and Indian myrrh.

The term is derived from the Aramaic ܡܪܝܪܐ (murr), meaning "bitter". Its name entered the English language from the Hebrew Bible where it is called mor, מור, and later as a Semitic loan word[5] was used in the Greek myth of Myrrha, and later in the Septuagint; in the Greek language, the related word μύρον became a general term for perfume.

So valuable has it been at times in ancient history that it has been equal in weight value to gold. During times of scarcity its value rose even higher than that.[source?] It has been used throughout history as a perfume, incense and medicine.

Usage

changeReligious ritual

changeMyrrh was used by the ancient Egyptians along with natron for the embalming of mummies.[source?]

Myrrh was a part of the Ketoret which is used when referring to the consecrated incense described in the Hebrew Bible and Talmud. It is also referred to as the HaKetoret (the incense). It was offered on the specialized incense altar in the time when the Tabernacle was located in the First and Second Jerusalem Temples. The ketoret was an important component of the Temple service in Jerusalem.

According to the book of Matthew 2:11, gold, frankincense, and myrrh were among the gifts to Jesus by the Biblical Magi "from out of the East." Because of its New Testament significance, myrrh is a common ingredient in incense offered during Christian liturgical celebrations (see Thurible).

In Roman Catholic liturgical tradition, pellets of myrrh are traditionally placed in the Paschal candle during the Easter Vigil. Eastern Christianity uses incense much more frequently, sometimes emphasizing its use at Vespers and Matins because of the Old Testament exhortation of the evening and morning offerings of incense.

Myrrh is also used to prepare the sacramental chrism used by many churches of both Eastern and Western rites. In the Middle East, the Eastern Orthodox Church traditionally uses myrrh-scented oil to perform the sacraments of chrismation and unction, both of which are commonly referred to as "receiving the Chrism".

Myrrh is also used in Neo-paganism and ritual magic.[source?]

Ancient medicinal use

changeSince ancient times, myrrh has been valued for its fragrance and its medicinal qualities as an aromatic wound dressing.

Chinese medicine

changeIn Chinese medicine, myrrh is classified as bitter and spicy, with a neutral temperature. It is said to have special efficacy on the heart, liver, and spleen meridians, as well as "blood-moving" powers to purge stagnant blood from the uterus. It is therefore recommended for rheumatic, arthritic, and circulatory problems, and for amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, menopause, and uterine tumors.

Its uses are similar to those of frankincense, with which it is often combined in decoctions, liniments, and incense. When used in concert, myrrh is "blood-moving" while frankincense moves the Qi, making it more useful for arthritic conditions.

It is combined with such herbs as notoginseng, safflower stamens, Angelica sinensis, cinnamon, and Salvia miltiorrhiza, usually in alcohol, and used both internally and externally.[6]

Ayurvedic medicine

changeMyrrh is used more frequently in Ayurveda and Unani medicine, which ascribe tonic and rejuvenative properties to the resin.

Myrrh (Daindhava) is used in many specially-processed rasayana formulas in Ayurveda. However, non-rasayana myrrh is contraindicated when kidney dysfunction or stomach pain are apparent, or for women who are pregnant or have excessive uterine bleeding.

A related species, called guggul in Ayurvedic medicine, is considered one of the best substances for the treatment of circulatory problems, nervous system disorders and rheumatic complaints.[7][8]

Modern medicine

changeIn a pharmacy, myrrh is used as an antiseptic in mouthwashes, gargles, and toothpastes[9] for prevention and treatment of gum disease.[10] Myrrh is currently used in some liniments and healing salves that may be applied to abrasions and other minor skin ailments. Myrrh has also been recommended as an analgesic for toothaches, and can be used in liniment for bruises, aches, and sprains.[11]

Scientific research

change- In an attempt to determine the cause of its effectiveness, researchers examined the individual ingredients of an herbal formula used traditionally by Kuwaiti diabetics to lower blood glucose. Myrrh and aloe gums effectively improved glucose tolerance in both normal and diabetic rats.[12]

- Myrrh was shown[13] to produce analgesic effects on mice which were subjected to pain. Researchers at the University of Florence (Italy) showed that furanoeudesma-1,3-diene and another terpene in the myrrh affect opioid receptors in the mouse's brain which influence pain perception.

- Mirazid, an Egyptian drug made from myrrh, has been investigated as an oral treatment of parasitic ailments including fascioliasis and schistosomiasis.[14]

- Myrrh has been shown to lower Cholesterol LDL (bad cholesterol) levels as well as to increase the HDL (good cholesterol) in various tests on humans done in the past few decades. One recent (2009) documented laboratory test showed this same effect on albino rats.[15]

Other "myrrh" plants

changeThe oleo gum resins of a number of other Commiphora and Balsamodendron species are also used as perfumes, medicines and incense ingredients. A lesser quality myrrh is bled from the tree Commiphora erythraea. Commiphora opobalsamum oleo gum resin is known as Opopinax, a name it shares with the gum resin bled from a species of parsnip Pastincea opobalsamum.

Fragrant "myrrh beads" are made from the crushed seeds of Detarium microcarpum, an unrelated West African tree. These beads are traditionally worn by married women in Mali as multiple strands around the hips.

The name "myrrh" is also applied to the potherb Myrrhis odorata otherwise known as "Cicely" or "Sweet Cicely".

See also

changeReferences

change- ↑ Rice, Patty C., Amber: Golden Gem of the Ages, Author House, Bloomington, 2006 p.321

- ↑ Caspar Neumann, William Lewis, The chemical works of Caspar Neumann, M.D.,2nd Ed., Vol 3, London, 1773 p.55

- ↑ Newnes, G., ed., Chambers's encyclopædia, Volume 9, 1959

- ↑ Anthony G. Miller, Thomas A. Cope, J. A. Nyberg Flora of the Arabian Peninsula and Socotra, Volume 1, Edinburgh University Press, 1996, p.20

- ↑ Klein, Ernest, A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the Hebrew Language for Readers of English, The University of Haifa, Carta, Jerusalem, p.380

- ↑ Michael Tierra. "The Emmenagogues"

- ↑ Michael Moore Materia Medica

- ↑ Alan Tillotson "Myrrh"

- ↑ "Species Information". www.worldagroforestrycentre.org. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ↑ Lawless, J. (2002) The Encyclopedia of Essential Oils, Harper Collins, p135

- ↑ "ICS-UNIDO – MAPs". www.ics.trieste.it. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ↑ Al-Awadi FM, Gumaa KA. Studies on the activity of individual plants of an antidiabetic plant mixture. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1987 Jan–Mar;24(1):37–41.

- ↑ Nature 1996, 379, 29

- ↑ See, for example, Soliman, OE et al., Evaluation of myrrh (Mirazid) therapy in fascioliasis and intestinal schistosomiasis in children: immunological and parasitological study. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2004 Dec;34(3):941–966.PubMed.gov

- ↑ Al-Amoudi, N. (2009). Hypocholesterolemic effect of some plants and their blend as studied on albino rats. International Journal of Food Safety, Nutrition and Public Health.

Further reading

change- Massoud A, El Sisi S, Salama O, Massoud A (2001). "Preliminary study of therapeutic efficacy of a new fasciolicidal drug derived from Commiphora molmol (myrrh)". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 65 (2): 96–99. PMID 11508399.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dalby, Andrew (2000). Dangerous Tastes: the story of spices. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-2720-5. (US ISBN 0-520-22789-1), pp. 107–122.

- Dalby, Andrew (2003). Food in the ancient world from A to Z. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23259-7., pp. 226–227, with additions

- Monfieur Pomet (1709). "Abyssine Myrrh)". History of Drugs. Abyssine Myrrh

- The One Earth Herbal Sourcebook: Everything You Need to Know About Chinese, Western, and Ayurvedic Herbal Treatments by Ph.D., A.H.G., D.Ay, Alan Keith Tillotson, O.M.D., L.Ac., Nai-shing Hu Tillotson, and M.D., Robert Abel Jr.

- Abdul-Ghani RA, Loutfy N, Hassan A. Myrrh and trematodoses in Egypt: An overview of safety, efficacy and effectiveness profiles. Parasitol Int. 2009;58:210–214( A good review on its antiparasitic activities) .

External links

change- History of Myrrh and Frankincense (www.itmonline.org)

- Myrrh article by James A. Duke (www.herbcompanion.com)

Category:Ayurvedic medicaments Category:Burseraceae Category:Incense Category:Medicinal plants Category:Resins Category:Spices Category:Plants used in Traditional Chinese medicine Category:Essential oils