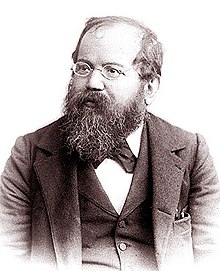

Wilhelm Steinitz

Wilhelm (later William) Steinitz (Prague, 17 May 1836 – New York, 12 August 1900) was an Austrian chess grandmaster who emigrated first to London, then to the USA.

| Wilhelm Steinitz | |

|---|---|

Wilhelm Steinitz | |

| Country | Austrian Empire, United States |

| World Champion | 1886–1894 (undisputed) |

He was the first undisputed World Chess Champion and held it from 1886 to 1894, unofficially from 1872.

Steinitz won the title by beating Johannes Zukertort in a match in 1886. He lost it to Emanuel Lasker in 1894. He also lost a rematch with Lasker in 1897.[1]

Life & career

changeBorn a Jew in Bohemia, Steinitz studied mathematics at the Vienna Polytecnic, and won the Vienna chess championship in 1861 with a score of 31/32. After playing in the London 1862 tournament, he stayed in London as a professional player in clubs and coffee houses. He won a series of matches against all the best English and other players living in London. This established him as one of the best player in the world.[2]

Steinitz beat Adolf Anderssen in 1866 and some think he should be regarded as world champion from this date however at the time Zukertort was the stronger player.[3]

Apart from the chess, this match was a landmark in chess organisation. It was the first event to be timed by clocks.[1]p82 The time for each move was recorded by hand. The totals for each player could then be added. This was the first practical step taken to make sure each player had the same total thinking time available. It had always been a problem that some players took much longer than others, unfairly so. Timing also helped to keep the total time for play within bounds. Eventually, special chess clocks were designed, and the idea has spread to other two-person games such as Go.

Steinitz beat Johannes Zukertort in 1872, and again later in 1886. This last match all agree was for the world championship. Zukertort was a brilliant and boastful player, who was also resident in London for many years. Both the men wrote for chess magazines, and there was a good deal of rivalry.

Steinitz did not win a really strong tournament until London 1872, and did not finish above Andersson until Vienna 1873. He came equal first at Vienna 1882, and second (to Zukertort) in London 1883, both top-class events. In general, his tournament play was not so outstanding as his match play. In match play he was the best of his day: he won 24 matches running until Lasker beat him.[1]p396

Style

changeAs a younger man, Steinitz played in the all-out attacking style that was common in the 1860s. Later, he developed a new positional style of play and demonstrated that it was superior to the previous style. His new style was controversial, and some even branded it as 'cowardly'. Some of Steinitz's games showed that it could also set up attacks as ferocious as those of the old school.

Steinitz was argumentative, and was often in disputes with other chess writers. He was a prolific writer in chess magazines, and defended his ideas vigorously. The debate was bitter and sometimes abusive: it became known as the 'Ink War'. By the early 1890s, Steinitz' approach was more widely accepted and the next generation of top players acknowledged their debt to him, especially his successor as world champion, Emanuel Lasker.

Lasker summed up the new style as:

- "In the beginning of the game ignore the search for combinations, abstain from violent moves, aim for small advantages, accumulate them, and only after having attained these ends search for the combination – and then with all the power of will and intellect, because then the combination must exist, however deeply hidden".[4]

United States

changeSteinitz left England for the United States in 1886, and became an American citizen in 1888.

He was given an enthusiastic reception, played several exhibitions, many casual games, a match for stakes of £50 with a wealthy amateur, and slightly more serious matches with New World professionals. The match with the Cuban champion Celso Golmayo Zúpide was abandoned when Steinitz was leading (eight wins, one draw, one loss). His hosts even arranged a visit to New Orleans, where Paul Morphy lived.[5][6]

While based in New York he played matches against Zukertort (St Louis 1883), twice against Russia's Mikhail Chigorin (Havana 1889 & 1892), Isidor Gunsberg (New York 1890/91). Finally, there were the two losing matches against Emanuel Lasker, (Philadelphia/New York/Montreal 1894 and Moscow 1896/97). These were all for the world championship. There were also a dozen matches against lesser masters, including four against J.H. Blackburne, the leading English professional.

Assessment

changeThe book of the Hastings 1895 chess tournament, written collectively by the players, described Steinitz as follows:[7]

- "Mr. Steinitz stands high as a theoretician and as a writer; he has a powerful pen, and when he chooses can use expressive English. He evidently strives to be fair to friends and foes alike, but appears sometimes to fail to see that after all he is much like many others in this respect. Possessed of a fine intellect, and extremely fond of the game, he is apt to lose sight of all other considerations, people and business alike. Chess is his very life and soul, the one thing for which he lives".

Steinitz died in poverty, having spent some of his last years in a New York mental institution. His second wife and their two young children survived him, and a fund of $1050 was raised to help them.[8]

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Hooper D. and Whyld K. 1992. The Oxford companion to chess. 2nd ed, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Hooper, David 1981. Wilhelm Steinitz. In Winter E. (ed) World chess champions, Pergamon.

- ↑ Winter E. Early uses of 'World chess champion'

- ↑ Lasker, Emanuel (1947). "The evolution of the theory of Steinitz". Lasker's Manual of Chess. David McKay. p. 199.

- ↑ Landsberger Kurt 2006. William Steinitz: chess champion. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2846-5.

- ↑ Landsberger K. 2002. The Steinitz Papers: letters and documents of the first world chess champion. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1193-7

- ↑ Pickard, Sid, ed. (1995). Hastings 1895: The centennial edition. Pickard. ISBN 1-886846-01-4.

- ↑ Obituary: "William Steinitz dead". New York Times. 14 August 1900. Retrieved 2008-11-19. Also available in 2 parts at "Steinitz Obituary (Part 1 of 2)". Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2008-11-19. and "Steinitz Obituary (Part 2 of 2)". Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- Bachmann L. 1910–1921. Schachmeister Steinitz. 4 vols, reprint Olms 1990.

- The games of Wilhelm Steinitz. ed Pickard & Son 1995. A collection of 1,022 Steinitz' games with annotations.

- Kasparov, Garry 2003. My great predecessors, part I. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-330-6.