Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 July 100 BC[1] – 15 March 44 BC) was a military commander, politician and author at the end of the Roman Republic.[2][3]

Julius Caesar | |

|---|---|

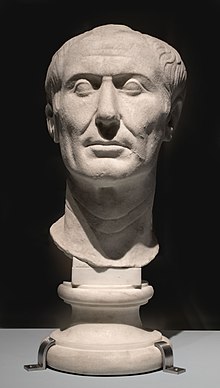

The Tusculum portrait, possibly the only surviving sculpture of Caesar made during his lifetime. Archaeological Museum, Turin, Italy | |

| Dictator of the Roman Empire | |

| In office October 49 BC – 15 March 44 BC | |

| Lieutenant | |

| Preceded by | Sulla (82/81–81 BC; as previous Dictator) |

| Succeeded by | Augustus (27 BC – AD 14; as Roman emperor) |

| Consul of the Roman Republic | |

| In office 1 January 44 BC – 15 March 44 BC Serving with Mark Antony | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by |

|

| In office 1 January 46 BC – September 45 BC Serving with M. Aemilius Lepidus (46 BC) | |

| Preceded by | |

| Succeeded by |

|

| In office 1 January 48 BC – 1 January 47 BC Serving with P. Servilius Vatia Isauricus | |

| Preceded by | |

| Succeeded by | |

| In office 1 January 59 BC – 1 January 58 BC Serving with Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus | |

| Preceded by | |

| Succeeded by | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Gaius Julius Caesar 12 July 100 BC Rome, Italia, Roman Republic |

| Died | 15 March 44 BC (aged 55) Rome |

| Cause of death | Multiple stab wounds |

| Resting place | Temple of Caesar, Rome |

| Political party | Populares |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | |

| Parents | Gaius Julius Caesar and Aurelia Cotta |

Caesar became a member of the First Triumvirate. When that broke up, he fought a civil war against Pompey the Great. Winning the war, Caesar became Roman dictator until his death.

On March 15, 44 BC, he was stabbed to death by a group of senators on the Ides of March before a meeting of the Senate at the Curia of Pompey (the Theatre of Pompey) in Rome.

Caesar is considered by many historians to be one of the greatest military commanders.[4] His surname is a synonym for "Emperor"; the title "Caesar" was used throughout the Roman Empire, giving rise to modern descendants such as "Kaiser" in German, "Tsar" in the Slavonic languages, and "Qayṣar" in the languages of the Islamic world.[5]

Early Life

changeGaius Julius Caesar was born in Italy in July 100 BC.

At sixteen he was the head of his family, and came under threat when Lucius Cornelius Sulla became Roman dictator.

Sulla set about purging Rome of his enemies. Hundreds were killed or exiled, and Caesar was on the list. His mother's family pleaded for his life; Sulla reluctantly gave in and removed Caesar from his inheritance. From then on, lack of money was one of the main problems in his life. Caesar joined the army and left Rome.

On the way across the Aegean Sea,[6] Caesar was kidnapped by pirates and held prisoner.[7] When the pirates thought to demand a ransom of twenty talents of silver, he insisted they ask for fifty.[8][9]p39 After the ransom was paid, Caesar raised a fleet, pursued and captured the pirates, and imprisoned them. He had them crucified on his own authority, as he had promised while in captivity—a promise the pirates had taken as a joke.[10] As a sign of leniency, he first had their throats cut. He was soon called back into military action.

On the way up

changeOn his return to Rome, he was elected as military tribune, a first step in a political career. He was elected quaestor for 69 BC.[11] His wife Cornelia died that year.[12] After her funeral, Caesar went to serve his quaestorship in Spain.[13]p100 On his return in 67 BC,[14] he married Pompeia (a granddaughter of Sulla), whom he later divorced.[15] In 63 BC he ran for election to the post of Pontifex Maximus, as high priest of the Roman state religion. He ran against two powerful senators; there were accusations of bribery by all sides. Caesar won comfortably, despite his opponents' greater experience and standing.[16]

After his praetorship, Caesar was appointed to govern Roman Spain, but he was still in considerable debt and needed to pay his creditors. He turned to Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of Rome's richest men. In return for political support, Crassus paid some of Caesar's debts and acted as guarantor for others. Caesar left for his province before his praetorship had ended. In Spain he conquered two local tribes, was hailed as imperator by his troops, and completed his governorship in high esteem.[17] Though he was due a 'triumph' in Rome, he also wanted to stand for Consul, the most senior magistracy in the Republic. Faced with the choice between a triumph and the consulship, Caesar chose the consulship. After election, he was a consul in 59 BC.[18]

The First Triumvirate

changeCaesar took power with Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) and Marcus Licinius Crassus. These three men ruled Rome and were called the Triumvirate.

Caesar was the go-between for Crassus and Pompey. They had been at odds for years, but Caesar tried to reconcile them. Between the three of them, they had enough money and political influence to control public business. This informal alliance, known as the First Triumvirate (rule of three men), was cemented by the marriage of Pompey to Caesar's daughter Julia.[19] Caesar also married again, this time to Calpurnia, who was the daughter of another powerful senator.[20]

Caesar proposed a law for the redistribution of public lands to the poor, a proposal supported by Pompey, by force of arms if need be, and by Crassus, making the triumvirate public. Pompey filled the city with soldiers, and the triumvirate's opponents were frightened.

Caesar's Gallic War

changeWith the agreement of his partners, Caesar became the governor of Gallia (Gaul). Gaul is the area which is today's Northern Italy, Switzerland, and France.

Caesar was the commander of the Roman legions during the Gallic War. The war was fought on the side of Rome's Gallic clients against the Germans, who wanted to invade Gaul. It was also to extend Rome's control of Gaul. Caesar's conquest of Gaul extended Rome's territory to the North Sea. In 55 BC he conducted the first Roman invasion of Britain. Caesar wrote about this eight-year war in his book De Bello Gallico ('About the Gallic Wars'). This book is an important historical account.

These achievements got him great military power, and threatened to overshadow Pompey. The balance of power was further upset by the death of Crassus in 53 BC.

Caesar's civil war

changeIn 50 BC, the Senate, led by Pompey, ordered Caesar to disband his army and return to Rome because his term as governor had finished.[21] Caesar thought he would be prosecuted if he entered Rome without the immunity enjoyed by a magistrate. Pompey accused Caesar of insubordination and treason.

Crossing the Rubicon

changeCaesar and his army approached Rome and crossed the Rubicon, a shallow river in north-east Italy, in 49 BC. It was the point beyond which no army was supposed to go. The river marked the boundary between Cisalpine Gaul to the north, and Italy proper to the south. Crossing the Rubicon caused a civil war. Pompey, the lawful Consul, and his friends, fled from Rome as Caesar's army approached.

Pompey managed to escape before Caesar could capture him. Caesar decided to head for Spain, while leaving Italy under the control of Mark Antony. Caesar made an astonishing 27-day route-march to Spain, where he defeated Pompey's lieutenants. He then returned east, to challenge Pompey in Greece. There, in July 48 BC, at Dyrrhachium Caesar barely avoided a catastrophic defeat. He then decisively defeated Pompey, at the Battle of Pharsalus later that year.[22]

Dictator at last

changeIn Rome, Caesar was appointed Dictator,[23] with Mark Antony as his Master of the Horse (second in command). Caesar presided over his own election to a second consulship and then, after eleven days, resigned this dictatorship.[23][24]

Late in 48 BC, he was appointed dictator again, with a term of one year. Caesar then pursued Pompey to Egypt, where Pompey was soon murdered.[25] Caesar then became involved in an Egyptian civil war between the child pharaoh and his sister, wife, and co-regent queen, Cleopatra. Perhaps as a result of the pharaoh's role in Pompey's murder, Caesar sided with Cleopatra. He is reported to have wept at the sight of Pompey's head,[26] which was offered to him by the pharaoh as a gift. In any event, Caesar defeated the pharaoh's forces in 47 BC and installed Cleopatra as ruler.

Caesar and Cleopatra celebrated their victory with a triumphant procession on the Nile in the spring of 47 B.C. The royal barge was accompanied by 400 additional ships, introducing Caesar to the luxurious lifestyle of the Egyptian pharaohs. Caesar and Cleopatra never married; Roman Law only recognized marriages between two Roman citizens. Caesar continued his relationship with Cleopatra throughout his last marriage, which lasted 14 years – in Roman eyes, this did not constitute adultery – and may have fathered a son called Caesarion. Cleopatra visited Rome on more than one occasion, staying in Caesar's villa, outside Rome across the River Tiber.

In 46 BC, Caesar defeated Cato and the remnants of Pompey's supporters in Africa. He was then appointed dictator for ten years. In two years he made numerous changes in Roman administration to improve the Republic. Many of these changes were meant to improve the lives of ordinary people. One example, which has lasted, was his reform of the calendar into the present format, with a leap day every four years.[27] In February of 44 BC, one month before his assassination, he was appointed Dictator for life.

Death

changeOn the Ides of March (15 March; see Roman calendar) of 44 BC, Caesar was due to appear at a session of the Senate. Mark Antony, fearing the worst, went to head Caesar off. The plotters expected this, and arranged for someone to intercept him.[28]

According to Eutropius, around sixty or more men participated in the assassination. He was stabbed 23 times.[29] According to Suetonius, a physician later established that only one wound, the second one to his chest, had been lethal.[30] The dictator's last words are not known with certainty, and are a contested subject among scholars and historians alike. The version best known in the English-speaking world is the Latin phrase Et tu, Brute? ('You too, Brutus?').[31][32] In Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, this is the first half of the line: "Et tu, Brute? Then fall, Caesar".[33] According to Plutarch, after the assassination, Brutus stepped forward as if to say something to his fellow senators; they, however, fled the building.[34] Brutus and his companions then marched to the Capitol while crying out to their beloved city: "People of Rome, we are once again free!". They were met with silence, as the citizens of Rome had locked themselves inside their houses as soon as the rumour of what had taken place had begun to spread.

A wax statue of Caesar was erected in the forum displaying the 23 stab wounds. A crowd who had gathered there started a fire, which badly damaged the forum and the neighbouring buildings. In the ensuing chaos, Mark Antony, Octavian (later Augustus Caesar), and others fought a series of five civil wars, which would end in the formation of the Roman Empire.

The Roman Empire and its emperors were so important in history that the word Caesar was used as a title in some European countries long after the Roman empire was gone. For example, Germany's emperor was called a Kaiser up to the year 1919 AD and Russia's emperor was called a Tsar until 1917 AD.

Caesar as author

changeCaesar was a significant author.

- The Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), campaigns in Gallia and Britannia during his term as proconsul; and

- The Commentarii de Bello Civili (Commentaries on the Civil War), events of the Civil War until immediately after Pompey's death in Egypt.

Other works historically attributed to Caesar, but whose authorship is doubted, are:

- De Bello Alexandrino (On the Alexandrine War), campaign in Alexandria;

- De Bello Africo (On the African War), campaigns in North Africa; and

- De Bello Hispaniensi (On the Hispanic War), campaigns in the Iberian peninsula.

These narratives were written and published on a yearly basis during or just after the actual campaigns, as a sort of "dispatches from the front". Apparently simple and direct in style—to the point that Caesar's Commentarii are commonly studied by first and second year Latin students—they are in fact quite sophisticated, aimed at the middle-brow readership of minor aristocrats in Rome, Italy, and the provinces.

Epilepsy

changeBased on remarks by Plutarch,[35] Caesar is sometimes thought to have suffered from epilepsy. Modern scholarship is divided on the subject. It is more certain that he was plagued by malaria, particularly during the Sullan proscriptions of the 80s.[36]

Caesar had four documented episodes of what may have been complex partial seizures. He may additionally have had absence seizures (petit mal) in his youth. The earliest accounts of these seizures were made by the biographer Suetonius who was born after Caesar died. The claim of epilepsy is countered among some medical historians by a claim of hypoglycemia. This can cause seizures which are a bit like epilepsy.[37][38][39]

In 2003, psychiatrist Harbour F. Hodder published what he termed as the "Caesar Complex" theory, arguing that Caesar was a sufferer of temporal lobe epilepsy, and that the symptoms were a factor in Caesar's decision to forgo personal safety in the days leading up to his assassination.[40]

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ The date of his birth is controversial. His 'official' birthday was on the 12th. [1]

- ↑ Fully, Caius Iulius Caii filius Caii nepos Caesar Imperator ("Gaius Julius Caesar, son of Gaius, grandson of Gaius, Imperator"). Official name after deification in 42 BC: Divus Iulius ("The Divine Julius").

- ↑ Robinson Jr., C.A. (May 1964). "Introduction". Selections from Greek and Roman historians. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. xxix.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer (2010). Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-59884-430-6.

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Julius-Caesar-Roman-ruler

- ↑ Again, according to Suetonius's chronology (Julius 4). Plutarch (Caesar 1.8–2) says this happened earlier, on his return from Nicomedes's court. Velleius Paterculus (Roman History 2:41.3–42) says merely that it happened when he was a young man.

- ↑ Plutarch, Caesar 1–2

- ↑ Thorne, James (2003). Julius Caesar: conqueror and Dictator. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 9780823935956.

- ↑ Freeman, Philip 2008. Julius Caesar. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-8953-6.

- ↑ Freeman, 40

- ↑ Freeman, p. 51

- ↑ Freeman, 52

- ↑ Goldsworthy, Adrian 2006. Caesar: life of a Colossus. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-12048-6.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, 101

- ↑ Suetonius. Julius 5–8; Plutarch, Caesar 5; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.43

- ↑ Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.43; Plutarch, Caesar 7; Suetonius, Julius, p.13

- ↑ Plutarch, Caesar 11–12; Suetonius, Julius 18.1

- ↑ Plutarch, Julius 13; Suetonius, Julius 18.2

- ↑ Cicero, Letters to Atticus 2.1, 2.3, 2.17; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.44; Plutarch, Caesar 13–14, Pompey 47, Crassus 14; Suetonius, Julius 19.2; Cassius Dio, Roman History 37.54–58

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 21

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 28

- ↑ Plutarch, Caesar 42–45

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Plutarch, Caesar 37.2

- ↑ Martin Jehne, Der Staat des Dicators Caesar, Köln/Wien 1987, p. 15-38.

- ↑ Plutarch, Pompey 77–79

- ↑ Plutarch, Pompey 80.5

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 40

- ↑ Huzar, Eleanor Goltz (1978). Mark Antony, a biography By Eleanor Goltz Huzar. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 9780816608638.

- ↑ Woolf Greg (2006), Et tu Brute? – the murder of Caesar and political assassination. ISBN 1-86197-741-7

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius, c. 82.

- ↑ Stone, Jon R. (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Latin Quotations. London: Routledge. p. 250. ISBN 0415969093.

- ↑ Morwood, James (1994). The Pocket Oxford Latin Dictionary (Latin-English). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198602839.

- ↑ The phrase appears in Richard Eedes's Latin play Caesar Interfectus of 1582 and The True Tragedie of Richarde Duke of Yorke &tc of 1595, Shakespeare's source work for other plays. Dyce, Alexander; (quoting Edmond Malone) (1866). The Works of William Shakespeare. London: Chapman and Hall. p. 648.

- ↑ Plutarch, Caesar 67

- ↑ Plutarch, Caesar 17, 45, 60; see also Suetonius, Julius 45.

- ↑ Ronald T. Ridley 2000. The Dictator's mistake: Caesar's escape from Sulla. Historia 49, 225–226, citing doubters of epilepsy: F. Kanngiesser, "Notes on the Pathology of the Julian Dynasty," Glasgow Medical Journal 77 (1912) 428–432; T. Cawthorne, "Julius Caesar and the Falling Sickness,” Proceedings of Royal Society of Medicine 51 (1957) 27–30, who prefers Ménière's disease; and O. Temkin, The Falling Sickness: a history of epilepsy from the Greeks to the beginnings of modern neurology (Baltimore 1971), p 162.

- ↑ Hughes J; Atanassova, E; Boev, K (2004). "Dictator Perpetuus: Julius Caesar—did he have seizures? If so, what was the etiology?". Epilepsy Behav. 5 (5): 756–64. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.05.006. ISSN 1525-5050. PMID 5380131. S2CID 34640921.

- ↑ Gomez J, Kotler J, Long J (1995). "Was Julius Caesar's epilepsy due to a brain tumor?". The Journal of the Florida Medical Association. 82 (3): 199–201. PMID 7738524.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ H. Schneble (1 January 2003). "Gaius Julius Caesar". German Epilepsy Museum. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ↑ Hodder, Harbour Fraser (September 2003). "Epilepsy and Empire, Caveat Caesar". Accredited Psychiatry & Medicine. 106 (1). Harvard, Boston: Harvard University: 19.