Trachea

This article does not have any sources. |

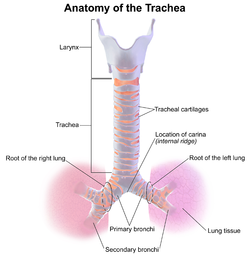

The trachea, or windpipe, is the bony tube that connects the nose and mouth to the lungs, and is an important part of the vertebrate respiratory system.

In mammals, the trachea begins at the lower part of the larynx and continues to the lungs. There it branches into the right and left bronchi. Inflammation of the trachea can lead to other conditions, such as tracheitis, which is the inflammation of the linings of the trachea.

Invertebrate trachea

changeThe invertebrate trachea refers to the open respiratory system of terrestrial arthropods. It consists of spiracles, tracheae, and tracheoles that take metabolic gases to and from tissues.[1] The distribution of spiracles varies, but in general each segment of the body has only one pair of spiracles, each of which connects to an atrium and has a relatively large tracheal tube behind it.

The smallest tubes, tracheoles, penetrate cells and diffuse water, oxygen, and carbon dioxide. Gas may be moved actively or by passive diffusion. Unlike vertebrates, insects do not generally carry oxygen in their haemolymph.[2] This is one of the factors that may limit their size.

A tracheal tube may contain ridge-like circumferential rings of taenidia in various geometries such as loops or helices. In the head, thorax, or abdomen, tracheae may also be connected to air sacs. Many insects, such as grasshoppers and bees, which actively pump the air sacs in their abdomen, are able to control the flow of air through their body. In some aquatic insects, the tracheae exchange gas through the body wall directly, in the form of a gill, or function as normal, via a plastron. Despite being internal, the tracheae of arthropods are shed during moulting (ecdysis).

References

change- ↑ Wasserthal, Lutz T. 1998. Chapter 25: The open hemolymph system of Holometabola and its relation to the tracheal space. In Microscopic anatomy of invertebrates. Wiley-Liss. ISBN 0-471-15955-7

- ↑ Westneat, Mark W.; et al. (2003). "Tracheal respiration in insects visualized with synchrotron X-ray imaging". Science. 299 (5606): 558–560. doi:10.1126/science.1078008. PMID 12543973. S2CID 43634044.