Mourning dove

The mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) is a member of the dove family (Columbidae).[Note 1] It has five subspecies. The number of mourning doves is about 475 million. They live in North America. Mourning doves are light grey and brown, and males and females look similar.

| Mourning dove | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mourning Dove Call | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Zenaida

|

| Binomial name | |

| Zenaida macroura (Linnaeus, 1758)

| |

| |

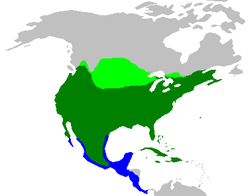

| Winter-only range Summer-only range Year-round range | |

These birds usually have one partner at a time. Both parents will sit on the eggs and care for their chicks. Adult mourning doves usually eat only seeds. The parents feed crop milk to the young.

People hunt mourning doves for sport and for meat. Up to 70 million birds are shot in the United States every year. Its name, "mourning," comes from its sad-sounding call. The bird is a strong flier, and can fly at up to 88 km/h (55 mph).

Distribution

changeMourning doves have a large range of nearly 11 million square kilometers (6.8 million square miles).[2][source?] These birds live throughout the Greater Antilles, most of Mexico, the Continental United States, and southern Canada. In the summer, the birds are mostly in the Canadian prairies, and in southern Central America in the winter.[3] The species is a vagrant in northern Canada, Alaska,[4] and South America. It has been seen at least seven times in the Palearctic ecozone with records from the British Isles (five), the Azores (one) and Iceland (one).[5] In 1963, the Mourning Dove was introduced to Hawaii, and in 1998 there was still a small population in North Kona, Hawaii.[6]

Mourning doves live in many different habitats, such as farms, prairie, grassland, and woods. It does not live in swamps or thick forests.[4] They also live in places where humans live, such as in cities or towns.[7]

Description

changeThe mourning dove is a medium-sized, slender dove. It weighs an average of 110 to 170 grams (4 to 6 oz).[8] It has a small head and a long tail. Mourning doves have perching feet, with three toes facing forward and one facing backward. The legs are short and reddish color. The beak is small and dark, usually a mixture of brown and black.[5]

Its feathers are generally light gray-brown and lighter and more pink below. The wings may have black spots, and the outer tail feathers are white. The eyes are dark, with light skin around them.[5] The adult male has bright purple-pink patches on the sides of its neck, with light pink coloring up to the breast. Younger birds look more scaly and dark.[5]

All five subspecies of the mourning dove look similar and cannot be told apart easily.[5] The Western subspecies has longer wings, a longer beak, shorter toes, and is lighter in color. The Panama mourning dove has shorter wings and legs, a longer beak, and is grayer in color. The Clarion Island subspecies has larger feet, a larger beak, and is darker brown.[3]

Sounds

changeThis species' call is a cooOOoo-wooo-woo-woooo, which is used by males when attracting a mate. Other sounds include a nest call (cooOOoo) by paired males to attract their mates to the nests, a greeting call (a soft ork) by males upon joining their mates again, and an alarm call (a short roo-oo) by either male or female when in danger. In flight, the wings make a fluttery whistling sound that is quiet and hard to hear, but is louder at take-off and landing.[5]

Reproduction and ecology

changeThe male begins courtship by flying noisily, and then in a graceful, circular glide with its wings outstretched and head down. After landing, the male will go to the female with a puffed out breast, bobbing head, and loud calls. Once the pair is mated, they will often spend time preening each other's feathers.[4] The mourning dove does not easily leave its mate.[3] Pairs may sometimes remain together throughout the winter. However, lone doves will find new partners if necessary.[9]

After mating, the male shows the female all the possible nest sites, and lets the female choose one and build the nest. The male will fly about, get material, and bring it to her. The male stands on the female's back to give the material to the female, who builds it into the nest.[10] The nest is made of twigs, conifer needles, or grass.[3] Sometimes, mourning doves will take place of the unused nests of other mourning doves, birds, or mammals such as squirrels.[3]

Most nests are in trees, but they can also be in shrubs, vines, or on buildings and hanging flower pots.[10] When there is no good place to nest above, mourning doves will nest on the ground.[3] The nest is almost always big enough for exactly two eggs.[10] Sometimes, however, a female will lay her eggs in the nest of another pair, leading to three or four eggs in the nest.[3] The eggs are small and white.

Both sexes incubate; the male from morning to afternoon, and the female the rest of the day and at night. Mourning doves rarely leave their nest alone.[10] Incubation takes two weeks.

Both parents feed the chicks crop milk for the first 3–4 days of life.[3][11][12] After that, they gradually begin to eat seeds. The feathers and wing muscles begin to develop for flight in about 11–15 days. This happens before the squabs are fully grown, but after they digest the adult food. They stay nearby to be fed by their father for up to two weeks after fledging.[4]

Mourning doves breed quickly. In warmer areas, these birds may raise up to six broods in a season.[4] This fast breeding is important because mourning birds die often. Each year, the mortality can reach 58% a year for adults and 69% for the young.[3]

Feeding

changeMourning doves eat mostly seeds. Seeds are at least 99% of their diet.[13] Rarely, they will eat snails or insects. Mourning doves usually eat enough to fill their stomach and then fly away to digest while resting. They often swallow gravel or sand to help them digest. At bird feeders, mourning doves are attracted to corn, millet, and sunflower seeds. Mourning doves do not dig or scratch for seeds, but only eat what they can see.[3] They will sometimes perch on plants and eat from them.[4]

Mourning doves especially prefer pine nuts, sesame, and wheat.[3] When they cannot find their favorite foods, mourning doves will eat the seeds of other plants, including buckwheat and rye.[3]

Predators and parasites

changeMourning doves can be easily harmed by several different parasites and diseases, including tapeworms, nematodes, mites, and lice. The Trichomonas gallinae, a parasite which lives in the mouth, is especially severe. While the bird sometimes shows no ill effects, the parasite often causes a yellowish growth in the mouth and throat. This can make the bird starve to death.[3]

The greatest predators of this species are birds of prey, such as falcons and hawks. Other times, during nesting, corvids, grackles, house cats or rat snakes will eat their eggs.[3] Cowbirds rarely pass parasites mourning dove nests. Mourning doves reject slightly under a third of cowbird eggs in such nests, and the cowbirds cannot eat the Mourning Dove's vegetarian diet.[14]

Behavior

changeLike other doves, the mourning dove drinks without lifting or tilting its head. They often gather at drinking spots around dawn and dusk.

Mourning doves wash themselves in the sun or rain. These birds can also take baths in shallow pools or bird baths. They may sometimes bathe themselves in the dust as well.

These birds are strong fliers and can fly up to 88 km/h (55 mph).[15]

When they are not breeding, mourning doves roost in dense deciduous trees or in conifers. During sleep, the head rests between the shoulders, close to the body, and is not tucked under the shoulder feathers as most species do. Sometimes, roosting is delayed on colder days during the winter in Canada.[16]

Conservation status

changeThe mourning dove is of Least Concern to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The species is not at immediate risk.[17] The population is about 475 million and they live across a wide area.[18] However, around 40–70 million birds are shot as game every year.[19]

Taxonomy

changeThe mourning dove is closely related to the eared dove (Zenaida auriculata) and the Socorro dove (Zenaida graysoni). Sometimes these three birds are put in the separate genus Zenaidura.[20] The Socorro dove was once thought to be the same species as the mourning dove. However, differences in behavior, call, and appearance separate them as two different species.[21]

There are five subspecies of mourning dove:

- Eastern Z. m. carolinensis (Linnaeus, 1766)

- Clarion Island Z. m. clarionensis (C.H.Townsend, 1890)

- West Indian Z. m. macroura (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Western Z. m. marginella (Woodhouse, 1852)

- Panama Z. m. turturilla (Wetmore, 1956)

The West Indian subspecies lives throughout the Greater Antilles.[3] It is also lives in the Florida Keys.[5] The Eastern subspecies lives mainly in eastern North America, as well as Bermuda and the Bahamas. The Western subspecies lives in western North America and parts of Mexico. The Panamanian subspecies is in Central America. The Clarion Island subspecies lives near the Pacific coast of Mexico.[3]

The mourning dove is sometimes called the American mourning dove, because it may be confused with the distantly related African mourning dove (Streptopelia decipiens). It also used to be called the Carolina turtledove or Carolina pigeon.[22] French zoologist Charles L. Bonaparte gave this species' its scientific name in 1838. They name comes from his wife, Princess Zénaide.[23] The "mourning" part of its name comes from its call.[24]

Closest relative

changeThe mourning dove is thought to be most closely related to the extinct passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius).[25][26][27]

As a symbol and in the arts

changeThe Eastern mourning dove (Z. m. carolinensis) is Wisconsin's official symbol of peace.[28] The bird is also Michigan's state bird of peace.[29]

The mourning dove appears as the Carolina turtle-dove on plate 286 of Audubon's The Birds of America.[22]

Mourning doves are referred to often in American literature. They are in some American and Canadian poetry such as in the works of Robert Bly, Jared Carter,[30] Lorine Niedecker,[31] and Charles Wright.[32]

Notes

change- ↑ The bird is also called the western turtle dove or American mourning dove or rain dove, and used to be known as the Carolina pigeon or Carolina turtledove.

References

change- ↑ "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species on Zenaida macroura (American Mourning Dove, Mourning Dove)". The IUNC Red List of Threatened Species. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 2012. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Mourning Dove – BirdLife Species Factsheet". Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 "Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura)" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Habitat Management leaflet 31. National Resources Conservation Services (NRCS). February 2006. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-395-77017-7.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Alderfer, Jonathan K (2006). National Geographic Complete Birds of North America. National Geographic. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-7922-4175-1.

- ↑ "Check-list of North American Birds" (PDF). American Ornithologists' Union. 1998. p. 224. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Mourning Dove". Bird Web.org. Seattle Audubon Society. 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ↑ Miller, Wilmer J. (January 16, 1969). "The biology and natural history of the mourning dove". Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

Mourning doves weigh 4–6 ounces, usually close to the lesser weight.

- ↑ Mauldin, Margaret (2012). "Dove hunting: mourning doves widely hunted in United States". Dove Society.org. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Mourning dove". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ Ehrlich, Paul R. et al (1988) "Bird Milk". Stanford University.

- ↑ Silver, Rae (1984). "Prolactin and parenting in the pigeon family" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 232 (3): 617–625. doi:10.1002/jez.1402320330. PMID 6394702. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 13, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ↑ Cornell Lab of Ornithology (2011). "Mourning Dove, Life History". All about birds. Cornell University. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ Brian Peer; Eric Bollinger (October 1998). "Rejection of cowbird eggs by mourning doves: a manifestation of nest usurpation?" (PDF). The Auk. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ Bastin E.W. 1952, Flight-speed of the mourning dove. Wilson Bulletin 64: 47.

- ↑ Doucette D.R., and Reebs S.G. 1994. Influence of temperature and other factors on the daily roosting times of mourning doves in winter. Canadian Journal of Zoology 72: 1287–1290.

- ↑ Birdlife International. "Mourning Dove – BirdLife Species Factsheet". Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved October 8, 2006.

- ↑ Mirarchi R.E., and Baskett T.S. 1994. Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura). In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds. The Birds of North America, #117. Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, DC: The American Ornithologists' Union.

- ↑ Sadler, K.C. (1993). Mourning Dove harvest. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

- ↑ "Eared dove (Zenaida auriculata)". the Internet Bird Collection. 2012. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Check-list of North American Birds" (PDF). American Ornithologists' Union. 1998. p. 225. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Audubon, John James (1990). "Plate CCLXXXVVI". Birds of America. Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-1-55859-128-8. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ Wells, Diana (2002). 100 Birds and How They Got Their Names. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. ISBN 978-1-56512-281-9.

- ↑ "Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) – Birds of Quinta Mazatlan". Quintamazatlan. 2012. Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia Smithsonian: The Passenger Pigeon". Encyclopedia Smithsonian. 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Biography of Mourning Dove". ringneckdove.com. 2006. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Dove History | MDC". MDC online. Missouri Department of Conservation. 2012. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ↑ Government of Wisconsin. "State Symbols". Archived from the original on January 12, 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ Audi, Tamara (October 16, 2006). "Dove hunting finds place on Mich. ballot". USA Today. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ Carter, Jared (2012). "Poems: 'Mourning Doves'". Jared Carter Poetry. Archived from the original on August 22, 2003. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Lorine Niedecker Poetry Selections". Friends of Lorine Niedecker, Inc. 2012. Archived from the original on October 18, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ↑ Wright, Charles. "Meditation on song and structure from Negative Blue: selected later poems". Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

Other websites

change- "More detailed information about breeding/nesting habits". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- Mourning Doves on the Internet Bird Collection

- USGS page

- Information from Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- South Dakota Birds page

- Mourning Dove Movies (Tree of Life)

- 28 Mourning Dove Photos Archived 2020-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Video of a Mourning Dove's Call

- Mourning Dove Bird Sound Archived October 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine