Pazyryk rug

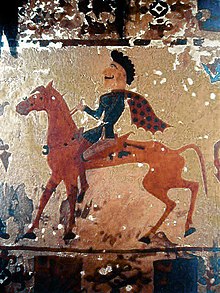

The Pazyryk rug is one of the oldest carpets in the world, dating around the 4th–3rd centuries BC. It is now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. The Pazyryk rug was found in 1949 in the grave of a Scythian nobleman in the Bolshoy Ulagan dry valley of the Altai Mountains in Kazakhstan. The Pazyryk rug had been frozen in the ice and it was very well preserved. The rug has a ribbon pattern in the middle, and a border which has deer, and warriors riding on horses.[1] All parts of the rug are made of wool, including the pile and the base.[2]

Being produced either in Ancient Armenia, Persia,[3][4] or Central Asia,[5] this carpet has 3600 symmetrical double knots per dm² (232 per inch²), in modern terminology also called "Ghiordes knot (or "Turkish knot").[5][6][7][8] The design and the systematic motifs of the Pazyryk rug would later be found in similar Turkmen carpets,[9][10] carpets of the early Seljuq period,[9] and subsequently modern Turkish carpets and kilims.[11][12]

Origins

changeThe origin of the rug is unknown.[5] There are different theories regarding the origin of the carpet. While a number of scholars presume a Oghuz-Turkic origin, Volkmar Gantzhorn assumes a Urartian and Armenian origin of the rug.[13] It is worth noting that the Oguz Turks Khanate didn't surface in the region until more than 1300 years later. A Persian theory also exists, but has not been further elaborated; The rug may have originated between the Iranian-Altaian corridor through ancient contacts.[5] Some authors assume that the wool, the artistic conception, as well as the workmanship, may have been provided by Armenians of the Near East; The rug itself is considered as a Sakic funeral accessory.[14] Although a previous study in 1983/1985 did not support an involvement of Armenian cochineal,[15] a Soviet-based conference held in Riga (1987) still maintained the claim that the red threads of the rug resemble those of the Armenian cochineal type.[16] Later it was found by an American research center (Bard Graduate Center, 1991) that the bluish-red color used for the rug and other felts was actually made from Polish cochineal (Porphyrophora polonica), a scale insect native to Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Western Siberia, or from one of the Porphyrophora species recently discovered in Kazakhstan: P. Altaiensis, P. Turaigiriensis (Jashenko, 1988), P. Akirtobiensis (Jashenko, 1988), P. eremospartonae (Jashenko, 1989), and P. matesovae (Jashenko, 1989).[17] Armenian authors, however, still insist in the Soviet-based perception of 1987.[18] Further confirmation on the nature of Ararat Kermes of the Armenian cochineal gained by the analysis of Porphyrophora hameli insects in 1990 by Harald Böhmer, has shown that the Pazyryk rug cannot have been dyed with this insect.[17]

Turkic interpretation

changeThe numerical values of the carpet show striking genealogical parallels to the Oghuz-Turkic legend, perhaps based on an older version of the Massageteans.[10] This genealogy is shown in the way the pattern is divided into 24 tribes. On the left and right their are groups of 12 tribes in each. According to Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, the founder of the Oghuz tribes had six sons, with each having four sons.[10] As mentioned in the “Shiji” (“Historical Records”) of Sima Qian this scheme was a result of the military administrative reform of the Xiongnu leader Modu Chanyu in 209/206-174 BC which in turn originated from the Turkic primordial ancestor Oghuz Khagan. Many Turkic cultures today use his legend to describe their ethnic origins. Historian Sergei Tolstov writes that this scheme “...was preserved by the Aral foreland Huns, the Kidarites-Hephthalites, and was inherited by their descendants, the tribes of the Oghuz alliance in the 10th – 11th centuries AD and, finally, by the Turkmens of the 19th century AD – beginning of the 20th century AD.”[19]

Armenian interpretation

changeGantzhorn supports the view that the Pazyryk rug is of Armenian origin. He put forward the hypothesis that the rug is actually not depicting Scythians, but Armenians. He found similarities at the ruins of Persepolis in Iran where various nations are depicted as bearing tribute, the horse design from the Pazyryk carpet is the same as the relief depicting part of the Armenian delegation.[13] Gantzhorn and Schurmann further stated, that the rug is weaved with the armenian double knot technique, and the red filaments color was made from Armenian cochineal.[20][21]

References

change- ↑ Carpet Encyclopedia: History of handknotted carpets - Carpet Encyclopedia, accessdate: December 24, 2015

- ↑ С. И. Руденко «Древнейшие в мире художественные ковры и ткани из оледенелых курганов Горного Алтая.»// М.: Искусство. 1968. 136 с.

- ↑ "History of handknotted carpets - Carpet Encyclopedia | Carpet Encyclopedia". www.carpetencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ↑ Dixon, Glenn. "The Age-Old Tradition of Armenian Carpet Making Refuses to Be Swept Under the Rug". 06 July 2018. smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Pile Carpet - Hermitage Museum "The Pazyryk carpet was woven in the technique of the symmetrical double knot, the so-called Turkish knot (3600 knots per 1 dm2, more than 1,250,000 knots in the whole carpet), and therefore its pile is rather dense. The exact origin of this unique carpet is unknown. There is a version of its Iranian provenance. But perhaps it was produced in Central Asia through which the contacts of ancient Altaians with Iran and the Near East took place. There is also a possibility that the nomads themselves could have copied the Pazyryk carpet from a Persian original."

- ↑ "Ghiordes knot" - Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed: July 20, 2020. "Ghiordes knot - Alternative Titles: Turkish knot, symmetrical knot"

- ↑ Wilfried Menghin, Im Zeichen des goldenen Greifen: Königsgräber der Skythen, Prestel, 2007, p.126: "Er wurde mit symmetrischen Doppelknoten (sogenannten türkischen Knoten) geknüpft. [...] Der Teppich hat eine sehr dichte Textur und ist ein seltenes Exemplar der vorder- und mittelasiatischen Knüpfkunst jener Zeit."

- ↑ D. T. Potts, A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Vol. 1, John Wiley & Sons, 2012, p.439: "Further afield, we have also learned much from important find from Siberia, most notably the famous 4th century BC pile carpet from Pazyryk (Rudenko 1970). This carpet is made up of ghiördes (symmetrical, or Turkish) knots with a count of 3,600 per square decimeter or about 6 knots per linear centimeter (15 knots per linear inch)."

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Peter Bausback, Antike Orientteppiche. 1978. p.429: "Die Muster des frühen Knüpfteppichs aus Pazyryk entsprechen in der Systematik den turkmenischen Erzeugnissen. Durch die Völkerverschiebungen in den verschiedenen Jahrhunderten waren die Turkmenensteppen die Durchgangsgebiete für die Wanderungen nach Westen. Hierdurch erklärt sich auch, daß frühe seldschukische Teppiche der Türkei mit dem Stil der Turkmenensteppe vieles gemeinsam haben."

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig, Jahrbuch, vol. 39, 1992, p.40-42: "Vergleicht man aber die Nomaden- und Bauernteppiche Vorder- und Mittelasiens untereinander und sucht nach Parallelen zum Pazyryk-Teppich, so ergibt sich, daß turkmenische Bodenteppiche dem von Pazyryk am nächsten stehen, und zwar durch Merkmale, die sie bezeichnenderweise von kaukasischen, persischen und türkischen unterscheiden. ... Sowohl auf dem Teppich von Pazyryk als auch bei turkmenischen Erzeugnissen dominiert die rote Farbe. Bei den Turkmenen wird der monochrome Eindruck noch dadurch verstärkt, dass das Rot nicht nur die Grundfarbe des Innenfeldes und meist auch der Bordüre, sondern auch die dominierende Farbe des Musters ist. ... Die Zahlenwerte des Pazyryk-Teppichs erscheinen aber erstaunlicherweise in der Oghuz-Legende wieder. Nach dem persischen Historiker Raschid ad-Din hatte der Stammvater der Oghuzen sechs Söhne, die ihrerseits wiederum je vier männliche Nachkommen hervorbrachten. Um Zwistigkeiten zu vermeiden, soll ein Ratgeber empfohlen haben, jedem der 24 Geschlechter ein eigenes Brandzeichen bzw. Siegel zu geben. Außerdem bekamen je vier gemeinsam einen Jagdvogel als „Totem". In ethnischer Hinsicht betrachtet Tolstow die Oghuzen als Hephtaliten, die sich mit türkischen Elementen, welche im 6.-8. Jh. aus dem Siebenstromland in das Gebiet östlich des Aral-Sees vorgedrungen waren, vermischt und neu formiert hatten. So versteht er die oghuzische Kultur des 10. Jh. „als gradlinige Weiterentwicklung der hephtalitischen des 5. und 6. Jh. Man kann davon ausgehen, daß auch die Oghuz-Legende auf einem älteren skythisch- massagetischen Motiv aufbaut, das bereits auf dem Pazyryk-Teppich seinen Niederschlag fand."

- ↑ W. T. Ziemba, Abdulkadir Akatay, Sandra L. Schwartz, Turkish flat weaves: an introduction to the weaving and culture of Anatolia, Scorpion Publications, 1979, p.44: "The following article discusses various theories concerning the age and provenance of the Pazyryk carpet and provide insights into designs and weaving of Turkish carpets and kilims woven much later. See also Rudenko (1970)."

- ↑ Virginia Dulany Hyman, William Chao-chung Hu, Carpets of China and its border regions, Ars Ceramica, 1982, p.10: "The Pazyryk carpet contains motifs which could be found in many variations throughout their historical development within Turkish and Hun art and they all bear a strong resemblance to their proto-types. Many of the elements found on the Pazyryk carpet can be traced through later Turkish rugs "I'm in deep awe how stupid some turkish people are that think changing wikipedia will change the history , it's abviously a persian rug and every decent historian will approve it easily , oh c'mon :)" ."

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Volkmar Gantzhorn, "Oriental Carpets", 1998, ISBN 3-8228-0545-9, pp.50-54

- ↑ Ulrich Schurmann, The Pazyryk. Its Use and Origin, during the Symposium of the Armenian Rugs Society, New York, September 26, Munich 1982, p.46

- ↑ M.C. Whiting, "A Report on the Dyes of the Pazyryk Carpet", in Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies, I, ed. R. Pinner and W. B. Denny (London: 1985), pp.18-22: "Thus this work does not support the possible identification of the dye pf the Pazyryk carpet (and of the fragments of Classical date examined by Pfister and ourselves) as Persian or Armenian cochineal or kirmiz." papers presented at the 4th International Conference on Oriental Carpets, London, June 1983, p.22

- ↑ USSR conference to exchange experiences leading restorers and researchers. The study, preservation and restoration of ethnographic objects. Theses of reports, Riga, 16–21 November 1987. pp. 17-18 (in Russian)

Л.С. Гавриленко, Р.Б. Румянцева, Д.Н. Глебовская, Применение тонкослойной хромотографии и электронной спектроскопии для анализа красителей древних тканей. Исследование, консервация и реставрация этнографических предметов. Тезисы докладов, СССР, Рига, 1987, стр. 17-18: "В ковре нити темно-синего и голубого цвета окрашены индиго по карминоносным червецам, нити красного цвета - аналогичными червецами типа aраратской кошенили." - ↑ 17.0 17.1 Harald Böhmer and Jon Thompson, "THE PAZYRYK CARPET: A TECHNICAL DISCUSSION", Notes in the History of Art, Vol. 10, No. 4, THE DATING OF PAZYRYK (Summer 1991), The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Bard Graduate Center, pp. 30-36: "It is the most northerly species, Porphyrophora polonica, that appears to have been used to dye the felt. [...] The red pile of the carpet was found to contain the same insect dye components as the felts. The ratio of carminic to karmesic acid was 8:1. [...] However, the presence in the carpet of a red dye derived from an insect found in the steppe region, as opposed to one availabe on or near the Iranian plateau (Ararat Kermes) that has been known and used since antiquity, is strong evidence that the Pazyryk carpet did not come from the Iranian plateau, but farther to the north. This finding supports the view that the steppe-related elements in its essentially Achaemenid* design indicate a Central Asian provenance." (* as described at page 30, the "Achaemenid design" refers only to the most northerly Central Asian part of the Achaemenid territory)

- ↑ Ashkhunj Poghosyan, On origin of Pazyryk rug, Yerevan, 2013 (PDF) pp. 1-21 (in Armenian), pp. 22-37 (in English)

- ↑ С.П. Толстов, Города гузов (историко-этнографические этюды). Советская этнография 3, 1947, 80. (PDF[permanent dead link])

- ↑ Ulrich Schurmann, The Pazyryk. Its Use and Origin, Munich, 1982, p.46

- ↑ Volkmar Gantzhorn, "Oriental Carpets", 1998, ISBN 3-8228-0545-9

Other websites

change- THE BEAUTY, WOVEN OF MYSTERIES is a 2018 documentary film directed by Emir Valinezhad about The World's Oldest Carpet Story