Roman Kingdom

The Roman Kingdom (Latin: Regnum Romanum) was the monarchical government of the city of Rome and its territories. No written records from the time survive. The histories about it were written during the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire and are largely based on legend. Therefore, not much is certain about the history of the Roman Kingdom.

Roman Kingdom | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 753 BC–509 BC | |||||||||||

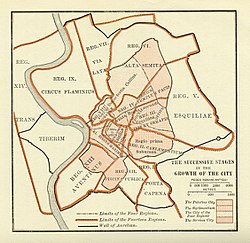

The ancient quarters of Rome | |||||||||||

| Capital | Rome | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Latin | ||||||||||

| Religion | Roman religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Elective monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 753–716 BC | Romulus | ||||||||||

• 715–673 BC | Numa Pompilius | ||||||||||

• 673–642 BC | Tullus Hostilius | ||||||||||

• 642–616 BC | Ancus Marcius | ||||||||||

• 616–579 BC | L. Tarquinius Priscus | ||||||||||

• 578–535 BC | Servius Tullius | ||||||||||

• 535–509 BC | L. Tarquinius Superbus | ||||||||||

| Legislature | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||||

| 753 BC | |||||||||||

| 509 BC | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

However, the history of the Roman Kingdom began with the founding of Rome, which is traditionally dated to 753 BC, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Roman Republic in about 509 BC.

Birth

changeWhat eventually became the Roman Empire began as settlements around the Palatine Hill along the River Tiber in central Italy. The river was navigable up to that place. The site had a ford at which the Tiber could be crossed. The Palatine Hill and the hills surrounding it presented easily-defended positions in the wide fertile plain surrounding them. All of those features contributed to the success of the city.

The traditional account of Roman history is that in the first centuries, Rome was ruled by a succession of seven kings. That traditional chronology is discounted by modern scholarship. The Gauls destroyed all of Rome's historical records when they sacked the city after the Battle of the Allia in 390 BC or 387/6 and so no contemporary records of the kingdom exist. All of the accounts of the kings must be questioned.[1]

Kings

changeAfter Romulus, who created the Senate, there were, according to legend, six more kings: Numa Pompilius, Tullo Ostilio, Anco Marzio, Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Tarquinius Superbus. After Romulus died, the Roman Senate could elect a new king, and after much debate between Romans and Sabines, it agreed to allow the Curiate Assembly to vote for a new king of Rome. It chose Numa Pompilius, who unlike Romulus was against war and thought that the best course for Rome was peace. He is credited with bringing religion into the average Roman everyday life.

The power of the kings was almost absolute, but the Senate had some influence. One important difference from other kingdoms was that kingship was not hereditary.

Election

changeWhenever a king died, Rome entered a period of interregnum. The supreme power of the state would go to the Senate, which was responsible for finding a new king. The Senate would assemble and appoint one of its own members, the interrex, to serve for a period of five days with the sole purpose of nominating the next king of Rome.

After the five-day period, the interrex would appoint another senator with the Senate's consent for another five-day term. The process would continue until a new king was elected. When the interrex found a suitable nominee to be king, he would bring the nominee before the Senate, who would review him. If the Senate passed the nominee, the interrex would convene the Assembly and preside over it during the election of the king.

Once proposed to the Assembly, the people of Rome could either accept or reject him. If accepted, the king-elect did not immediately enter office. Two other acts still had to take place before he was invested with the full regal authority and power.

It was first necessary to obtain the divine will of the gods for his appointment by means of the auspices since the king would serve as high priest of Rome. The ceremony was performed by an augur, who conducted the king-elect to the citadel, where he was placed on a stone seat as the people waited below. If the king was found worthy of the kingship, the augur announced that the gods had given favourable tokens to confirm the king’s priestly character.

The second act that had to be performed was the conferral of the imperium upon the king. The Assembly’s previous vote determined only who was to be king, not whether he had the necessary power. Accordingly, the king himself proposed to the Assembly a law granting him imperium, and the Assembly granted it by voting for the law.

In theory, the people of Rome elected their leader, but the Senate had most of the control over the process.

Romulus

changeRomulus was Rome's first king and the city's founder, and the two names are clearly linked. In 753 BC, Romulus began building the city upon the Palatine Hill. The story goes that after founding and naming Rome, he permitted men of all classes to come to Rome as citizens, including slaves and freemen without distinction.[2] To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighbouring tribes to a festival in Rome, where he abducted the young women from amongst them (known as the Rape of the Sabine Women). After the ensuing war with the Sabines, Romulus shared the kingship with Sabine King Titus Tatius.[2]

Romulus selected 100 of the best men to form the Senate as an advisory council to the king. He called them patres, and their descendants became the patricians. He also divided the general populace into thirty curiae, named after thirty of the Sabine women who had intervened to end the war between Romulus and Tatius. The curiae formed the voting units in the Roman assemblies: Comitia Curiata.[2]

In addition to the war with the Sabines and other tribes after the Rape of the Sabine Women, Romulus waged war against the Fidenates and the Veientes.[2] After his death at the age of 54, Romulus was deified as the war god Quirinus and served not only as one of the three major gods of Rome but also as the deified likeness of the city of Rome.

Tarquinius Superbus

changeThe seventh and final king of Rome was Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. He was of Etruscan birth, and during his reign, the Etruscans reached their apex of power. More than other kings before him, Tarquinius used violence, murder and terrorism to maintain control over Rome. He repealed many of the earlier constitutional reforms of his predecessors.

A sex scandal brought down the king. Allegedly, Tarquinius allowed his son, Sextus Tarquinius, to rape Lucretia, a patrician Roman. Sextus had threatened Lucretia that if she refused to have sex with him, he would kill a slave and her and have their bodies discovered together to create a gigantic scandal. Lucretia then told her relatives about the threat and then committed suicide to avoid any such scandal. Lucretia’s kinsman, Lucius Junius Brutus (an ancestor of Marcus Brutus), summoned the Senate and had Tarquinius and the monarchy expelled from Rome in 510 BC.

Etruscan rule in Rome thus came to a dramatic end in 510 BC, which also signalled the downfall of Etruscan power in Latium.[3]

Lucius Junius Brutus and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, a member of the Tarquin family and Lucretia's widower, went on to become the first consuls of Rome's new government, the Roman Republic. The new government would lead the Romans to conquer most of the Mediterranean world. It would survive for the next 500 years until the rise of Julius Caesar and Octavian.

Many years later, during the Roman Republic, the strong Roman opposition to kings was used by the Senate to support the murder of the agrarian reformer Tiberius Gracchus.

References

change- ↑ Asimov, Isaac. Asimov's chronology of the World. New York: HarperCollins, 1991. p69

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1

- ↑ Cary M. & Scullard H.H. 1979. A History of Rome, 3rd ed. p55 ISBN 0-312-38395-9.