Warsaw Uprising

In 1944, the Polish resistance Home Army rebelled against Nazi occupation of Warsaw. This rebellion is known as the Warsaw Uprising. The resistance Home Army wanted to free Warsaw from Nazi Germany. The resistance army fought against German troops for 63 days. After that, there was no chance of winning, so they surrendered. German troops killed many civilians in the city. After the uprising, the city of Warsaw was destroyed almost completely. At the time of the uprising, the Red Army was stationed on the other side of the river Vistula, which runs through the city of Warsaw.

| Warsaw Uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Tempest, World War II | |||||||

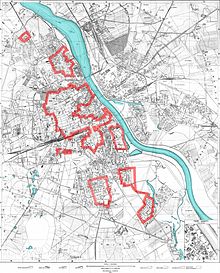

Polish Home Army positions, outlined in red, on day 4 (4 August 1944) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

(18 September only) |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski (POW) Tadeusz Pełczyński (POW) Antoni Chruściel (POW) Karol Ziemski (POW) Edward Pfeiffer (POW) Leopold Okulicki Jan Mazurkiewicz Konstantin Rokossovsky Zygmunt Berling |

Walter Model Nikolaus von Vormann Rainer Stahel Erich von dem Bach Heinz Reinefarth Bronislav Kaminski Petro Dyachenko | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Range 20,000[3] to 49,000[4] (initially) | Range 13,000[5] to 25,000[6] (initially) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Polish insurgents: 150,000–200,000 civilians killed,[8] 700,000 expelled from the city.[7] |

German forces: 310 tanks and armoured vehicles, 340 trucks and cars, 22 artillery pieces and one aircraft[7] | ||||||

The Uprising was the largest attack done by any European resistance movement of World War II.[9] The Slovak National Uprising, which happened from 29 August to 28 October 1944, is comparable.

Overview

changeAt the same time as the attack, the Soviet Union's Red Army got close to the east of the city and the German forces retreated.[10] However, the Soviets stopped moving forward. This allowed the Germans to destroy the city and defeat the Polish resistance.

The Warsaw uprising began on 1 August 1944. It was part of a big plan, Operation Tempest. Operation Tempest started when the Soviet Army got near Warsaw. The goals of the Polish resistance were to push the German troops out of the city. They also wanted to free Warsaw before the Soviets arrived. This would help the Polish Underground State to take control of the city.

At the start of the battle, the Polish resistance got control over most of central Warsaw. By 14 September, Polish forces under Soviet command captured the east bank of the Vistula river.

Winston Churchill asked Stalin and Franklin D. Roosevelt to help the Polish troops, but the Soviets would not help. Churchill sent over 200 drops of supplies by air. The US Army Air Force sent one drop of supplies by air.

About 16,000 members of the Polish resistance were killed and about 6,000 were badly wounded. In addition, between 150,000 and 200,000 Polish civilians were killed. The Germans also found many Jews the Poles were hiding.

More than 8,000 German soldiers were killed or went missing, and 9,000 were wounded. During the fighting in the city about a quarter of Warsaw's buildings were destroyed. After the surrender of Polish forces, German troops destroyed 35% of the city.

Background

changeBy July 1944, Poland had been occupied by Nazi German troops for almost five years. The Polish Home Army was loyal to the Polish government in London. It had planned to attack the Germans. Germany was fighting a group of Allied powers, led by the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States.

At the start, the plan of the Home Army was to join with the invading forces of the Western Allies as they freed Europe from the Nazis. In 1943, the Soviets were about to reach the pre-war borders of Poland before the Allied invasion of Europe got very far.[11]

The Soviets and the Poles were both enemies of Nazi Germany. But they had different goals. The Home Army wanted a democratic capitalist Poland that was allied with the West. The Soviet leader Stalin wanted to make Poland a communist country that was allied to the Soviet Union.

The Soviets and the Poles did not trust each other. Soviet partisans in Poland often disagreed with Polish resistance troops that were allied to the Home Army.[12]

Stalin stopped all Polish-Soviet relations on 25 April 1943 after the Germans told the world about the Katyn massacre of Polish army officers. Stalin refused to admit that he ordered the killings.

The Home Army commander, Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski made a plan on 20 November, called Operation Tempest. On the Eastern Front, local units of the Home Army were to attack the German Wehrmacht and help Soviet troops.

Evening before the battle

changeOn 13 July 1944 as the Soviet attack crossed the old Polish border, the Poles had to make a decision. They could either start to attack the Germans, which might not be supported by the Soviets, or do no attacks and be criticized by the Soviets.

The Poles were worried that if Poland was freed from German occupation by the Red Army, then the Allies would not accept the Polish government in London after the war.

When the Poles saw the actions of the Soviet forces, they realized they needed to make a decision. In Operation ''Ostra Brama'', NKVD forces shot or arrested Polish officers and forced lower ranks to join the Soviet-controlled Polish forces.[13]

On 21 July, the Home Army decided to launch Operation Tempest in Warsaw soon.[14] The plan was intended as a way of showing Poland was its own country and as an attack against the German occupiers.[7] On 25 July, the Polish government-in-exile (against the views of Polish Commander-in-Chief General Kazimierz Sosnkowski[15]) approved the plan for an uprising in Warsaw.[16]

In the early summer of 1944, German plans required Warsaw to be the defensive centre of the area. The Germans wanted to hold on to Warsaw no matter how many losses they had. The Germans had built fortifications and sent many new troops to the area. This slowed after the failed '20 July plot' to kill Adolf Hitler. The German troops in Warsaw were weak and did not feel confident.[17][18]

However, by the end of July, German forces in the area had new troops sent to them.[17] On 27 July, the Governor of the Warsaw District, Ludwig Fischer, called for 100,000 Polish men and women to build fortifications around the city.[19] The inhabitants of Warsaw did not follow his demand.

The Home Army became worried about possible revenge actions by the Germans or mass arrests, which would make it hard for the Poles to start an attack.[20] The Soviet forces were approaching Warsaw, and Soviet-controlled radio stations called for the Polish people to attack the Germans.[17][21]

On 25 July, the Union of Polish Patriots made a radio broadcast from Moscow. It told Poles to attack the Germans.[22] On 29 July, the first Soviet tanks reached the edges of Warsaw. They were counter-attacked by two German Panzer Corps: the 39th and 4th SS.[23] On 29 July 1944 Radio Station Kosciuszko located in Moscow told Poles to "Fight The Germans!".[24][25]

Bór-Komorowski and several senior officers held a meeting on that day. Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, who had arrived from London, said support from the Allies would be weak.[26] On 31 July, the Polish commanders General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski and Colonel Antoni Chruściel ordered the Home Army forces to be ready by 17:00 the following day.[27]

Wola massacre

changeDuring the uprising, Heinrich Himmler had given the order to storm Wola, a part of Warsaw. The rebels were holding this quarter. Himmler ordered that all people in Wazaw, who were not German, must be killed. This order was applicable to both civilians, and fighters, and also did not take into account if the people supported the uprising. With this order, Himmler wanted to break down the resistance of the Polish people against the German occupation. As a result, there were mass killings of people, mostly between August 5 and August 7. Estimates are that between 20,000 and 30,000 civilians were killed. in these three days. According to sources, about 20 German soldiers were killed, about 40 were wounded. Until August 12, about 50,000 Polish civilians lost their lives in Wola.

References

change- ↑ Davies, Norman (2004). Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-48863-1.

- ↑ Neil Orpen (1984). Airlift to Warsaw. The Rising of 1944. University of Oklahoma. ISBN 978-83-247-0235-0.

- ↑ Borodziej, Włodzimierz (2006). The Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Translated by Barbara Harshav. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-20730-4 p. 74.

- ↑ Borowiec, Andrew (2001). Destroy Warsaw!: Hitler's Punishment, Stalin's Revenge. Praeger Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-275-97005-5.

- ↑ Borodziej, p. 75.

- ↑ Comparison of Forces, Warsaw Rising Museum

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 "FAQ: Warsaw Uprising 1944". Project InPosterum website. 2013. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 179.

- ↑ (POL)Jerzy Janusz Terej, Europa podziemna 1939-1945, Warszawa 1974 Archived 2017-11-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Stanley Blejwas, A Heroic Uprising in Poland , 2004

- ↑ Davies, pp. 204–206.

- ↑ "Poland in Exile - The Warsaw Rising". www.polandinexile.com. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ↑ The NKVD Against the Home Army (Armia Krajowa) Archived 2021-01-21 at the Wayback Machine, Warsaw Uprising, based on Andrzej Paczkowski. Poland, the "Enemy Nation", pp. 372–375, in Black Book of Communism. Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press, London, 1999.

- ↑ Davies, p. 209.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 4 and Davies, p. 213.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Part 1 – "Introduction"". Poloniatoday.com. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ↑ "Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego". www.1944.pl. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ↑ Davies, p. 117.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 5.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 4 and Davies, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ The Tragedy of Warsaw and its Documentation, by the Duchess of Atholl D.B.E. Hon. D.C.L. LL.D. F.R.C.M. (1945, London)

- ↑ David M. Glantz (2001). The Soviet-German War 1941–1945: Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay Retrieved on 24 October 2013

- ↑ Pomian, Andrzej. The Warsaw Rising: A Selection of Documents. London, 1945

- ↑ "full text of broadcast". Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej (2006). The Warsaw Uprising of 1944. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 69, 70. ISBN 978-0-299-20730-4. [1]

- ↑ Davies, p. 232.