Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (1734 – 1820) was an American explorer and frontiersman. He is probably most famous for exploring Kentucky when it was not yet a US state.

Daniel Boone | |

|---|---|

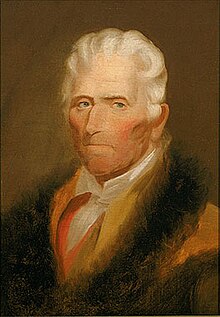

The only portrait of Boone painted from life | |

| Born | November 2, 1734 in Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died | September 26, 1820 |

| Education | None |

| Signature | |

In 1769, he made the Wilderness Road, a trail through the Appalachian Mountains from North Carolina and Tennessee and through Kentucky. He spent the last 20 years of his life in Missouri.

Early life

changeBoone was born on November 2, 1734 (N.S.).[a][1] Boone's grandfather, George Boone, a Quaker, immigrated from England in 1717.[2]

Boone was born in Berks County, Pennsylvania, the son of Squire Boone and Sarah Morgan.[2] His father was a weaver, and his mother ran the family farm.[2] In addition to his chores on the farm, Boone learned to hunt, fish, and trap.[2]

When he was 15, his family moved to the Yadkin Valley, in North Carolina.

French and Indian War

changeBoone was a part of an British expedition in 1755 into French territory. When the column was attacked by Indians allied to the French, the British commander, General Edward Braddock, was mortally wounded, and many of the soldiers were killed as well.[3]

That was at the Battle of the Monongahela in which Colonel George Washington rallied the British and the Virginia militia into an organized retreat.[3] Boone, who was the supervisor of the wagon train, was one of those who retreated with Washington.[3] He returned to North Carolina and settled on a farm near his father's farm. In 1756, he married Rebecca Bryan.[2]

In 1757, there were several more British defeats, but life on Boone's farm remained peaceful.[4] In 1758, the British had several victories over the French, but their Cherokee allies also became tired of their poor treatment by the British and the Americans.[4] The French took advantage of that and encouraged the Cherokees to attack American homesteads. In 1759, the Indians attacked in Virginia and North and South Carolina.[4]

To protect their families, many settlers left their farms for safer areas. Boone took his wife, two young sons, and all of the belongings that they could carry into a single wagon to Culpeper County, Virginia.[4]

To make a living, Boone hauled tobacco to market in Fredericksburg, Virginia.[4] In 1763, Boone and his family returned to their farm in North Carolina.[5]

Kentucky

changeBoone first heard of the lands of Kentucky while he was serving with General Braddock in 1755 from was John Findley, another member of the wagon train.[6] Findley had been there ti trade at a Shawnee village called Blue Lick.[6] He talked about Kentucky as a paradise full of wild game. Boone decided he had to see Kentucky. On a long hunt in the winter of 1767–1768, he, his brother Squire and a friend named William Hill moved west to try to find Kentucky.[6] They reached as far as what is now Prestonsburg, Kentucky, where they remained the rest of the winter. Not realizing that they had reached Kentucky, they returned to North Carolina in the spring. Boone again met Findley and asked him for the route from North Carolina to Kentucky. Findley was not a backwoodsman, but he knew of a trail that the Cherokee used when they fought in the Carolina colonies. In the summer of 1769, Boone and five companions used the warriors' trail to get to Kentucky. They hunted and explored the area. Most of his friends were killed or captured by Indians, but Boone and his brother escaped every time.[7] He made another attempt to reach the eastern Kentucky in 1763 but had to turn back. In 1775, he founded the settlement of Boonesborough, Kentucky.[7]

In 1778, Boone and a party were gathering salt when they were attacked by Indians.[7] Boone was captured and taken to Detroit, where the Indians made him a member of their tribe. Boone soon escaped and returned to Boonesborough.[7]

In one of the last battles of the American Revolutionary War, Boone, a lieutenant-colonel, was at the Battle of Blue Licks on 19 August 1782 in which the Americans were led into an ambush.[7] Boone was one of the last to retreat.

His son Israel Boone was killed in the battle. Boone was the hero of the battle, but other leaders had not listened to his warnings of a trap.[7]

Boone remained a leading figure in Kentucky for the next 24 years.[5] However, a series of defective land titles and cheating from land speculators made Boone lose all off his lands in Kentucky.[7]

There were swarms of people coming into Kentucky, and Boone felt crowded.[8] Kentucky was no longer the wilderness that it had been when he had first come there. He now wanted to discover new lands and so he was drawn to the wilds of what is now eastern Missouri.[8]

Louisiana Territory

changeIn 1799, Boone moved with much of his extended family to what is now Warren County, Missouri. It was then part of Spanish Louisiana, but it later became part of Missouri.[b] The Spanish were eager to promote settlement in the sparsely-populated region and so they did not enforce the requirement for all immigrants to be Roman Catholic. The Spanish governor appointed Boone "syndic" (Justice of the peace) of the Femme Osage district.[10] Boone served as syndic and commandant until 1804, when the area became part of the Louisiana Purchase. His land grants from the Spanish government had been largely based on verbal agreements, but the former lieutenant-governor, Zenon Trudeau, made the promise in writing, and Boone's lands were confirmed. However, Boone had not made the necessary improvements under the law and so the lands were again taken away. Around 1810, Boone sent a petition to Congress to restore his lands. It passed a special bill, which was signed by U.S. President James Monroe on 10 February 1814.[11]

Boone spent his final years in Missouri, often in the company of children and grandchildren, and continued to hunt and trap there as much as his health and energy levels permitted. He died on 26 September 1820 just before sunrise.[12] His body was taken to Charette, Louisiana Territory (now Marthasville, Missouri) and was buried next to his wife, Rebecca.[12]

Graves

changeIn 1845, a group from Kentucky removed the bones of Daniel and Rebecca Boone from their cemetery in Missouri[13] and took them to Frankfort, Kentucky to be buried in a tomb there. Reverend Philip Fall made a plaster cast of the skull of the body that had been removed from Missouri. The plaster cast was then presented to the Kentucky State Historical Society.[13] In 1862 the State of Kentucky created a monument over the grave in the Frankfurt cemetery.[13]

A forensic anthropologist, Dr. David Wolf, examined the plaster cast and stated that it was probably of a black slave.[14] Wolf said that the cast made by Fall did not provide enough evidence to be certain, but several clues also point to the conclusion that it may not be Boone.[14] Wolf stated that he did not believe the skull shape, slope of the brow, the brow ridges, and occipital bone to be Caucasian. The body removed from Missouri was that of a "large and robust man." According to Boone's brother-in-law Daniel Bryan described Boone as having a height of about 5 ft 8 or 9 in tall, blonde hair, and blue eyes.[14]

Several Missouri historians have stated that the bones taken from the Missouri cemetery were actually those of a slave. When Boone died at 85, the gravediggers discovered that an unmarked body had been buried next to Rebecca Boone (died 1813). The stranger was left in his grave and Daniel was buried at the foot of his wife's grave, but 16 years later, a gravestone was mistakenly placed over the stranger's grave. When the party from Kentucky took the bodies in 1845, it took the bodies of Rebecca and the stranger next to her who, was wrongly marked as Daniel Boone.[14] Both states claim to have the actual grave of Daniel Boone.

Notes

change- ↑ This is adjusted to the current calendar. Boone was born on 2 November 1734 O.S. He died on 26 September 1820 N.S. During his lifetime, the calendar changed from the Julian calendar to the present Gregorian calendar in 1752 and so his date of birth was adjusted.[1]

- ↑ Missouri became a state less than a year after Boone died.[9]

References

change- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 John Bakeless, Daniel Boone: Master of the Wilderness (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), p. 7 & note *

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 John Paul Zronik, Daniel Boone: Woodsman of Kentucky (New York: Crabtree Publishing Co., 2006), pp. 8–9

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 Joseph J. Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (New York: Random House, 2004), p. 22

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Lyman Copeland Draper, The Life of Daniel Boone (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998), pp. 145–48

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 R. P. Letcher and John G. Tompkins, 'Daniel Boone and the Frankfort Cemetery', The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 50, No. 172 (July 1952), p. 201

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 John Mack Faragher, Daniel Boone: The Life and Legend of an American Pioneer (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2013), pp. 69–72

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 John Wilson Townsend, 'Daniel Boone', Register of Kentucky State Historical Society, Vol. 8, No. 24 (September, 1910), pp. 17–18

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Michael A. Lofaro, 'The Many Lives of Daniel Boone', The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 102, No. 4 (Autumn 2004), p. 503

- ↑ Robert Maddex, State Constitutions of the United States (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 2006), p. 211

- ↑ John Bakeless, Daniel Boone: Master of the Wilderness (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, (1989), pp. 373–74

- ↑ John Bakeless, Daniel Boone: Master of the Wilderness (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, (1989), pp. 377–82

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Michael A. Lofaro, Daniel Boone: An American Life (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003), p. 177

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 Philip Fall Taylor, 'The Plaster Cast of Daniel Boone's Head', Register of Kentucky State Historical Society, Vol. 5, No. 15 (September, 1907), p. 22

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 AP (21 July 1983). "The Body in Daniel Boone's Grave May Not Be His". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 September 2014.