Historical race concepts

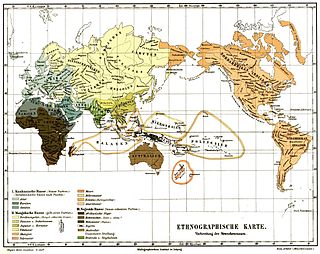

People from different places tend to look different. Some scientists in the 18th century decided to classify them into a limited number of variants or races. Some spoke of three races of mankind: The Caucasian race living in Europe, North Africa and West Asia, the Mongoloid race living in East Asia, Australia, and the Americas, and the Negroid race living in Africa south of the Sahara. Others preferred two, with the others arising from mixtures, and some chose four, five, or other numbers of races.

| Caucasoid: Negroid: Uncertain: | Mongoloid: North Mongol |

These ideas were popular from the late 18th century to the middle of the 20th century. These are now called historical definitions of race or historical race concepts. Today, scientists agree that there is only one human race. Modern genetic research has shown that the idea of three (or four, or five) races was wrong.[1][2]: 360

19th century

changeJohann Friedrich Blumenbach's classification, first proposed in 1779,[3] was widely used in the 19th century, with many variations.

- Ethiopian/black race.

- Caucasian race/white race

- Mongolian/yellow race

- American/red race

- Malayan/brown race

Middle of the 20th century

changeThe mid-twentieth century racial classification by American anthropologist Carleton S. Coon, also used five races but divided some of them differently:

- Negroid (Black) race

- Australoid (Australian Aborigine and Papuan) race

- Capoid (Bushmen/Hottentots) race

- Mongoloid (Oriental/Amerindian) race

- Caucasoid (White) race

Racism

changeThere was much prejudice based upon this way of thinking and speaking. It argued that in the races that make up the human race, there are deep, biologically determined differences.

Someone who partakes in racism is called racist. These are the attitudes that in turn supported the horrors of African slavery, Apartheid, the Jim Crow laws, Nazism, Japanese imperialism, and other crimes against humanity.

References

change- ↑ American Association of Physical Anthropologists (27 March 2019). "AAPA Statement on Race and Racism". American Association of Physical Anthropologists. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ↑ Templeton A. 2016. Evolution and notions of human race. In Losos J. & Lenski R. (eds) How evolution shapes our lives: essays on biology and society (pp. 346-361). Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv7h0s6j.26. That this view reflects the consensus among American anthropologists is stated in: Wagner, Jennifer K.; Yu, Joon-Ho; Ifekwunigwe, Jayne O.; Harrell, Tanya M.; Bamshad, Michael J.; Royal, Charmaine D. (February 2017). "Anthropologists' views on race, ancestry, and genetics". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 162 (2): 318–327. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23120. PMC 5299519. PMID 27874171.

- ↑ The anthropological treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. Google Books The anthropological treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

- ↑ American Association of Physical Anthropologists (27 March 2019). "AAPA Statement on Race and Racism". American Association of Physical Anthropologists. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

Instead, the Western concept of race must be understood as a classification system that emerged from, and in support of, European colonialism, oppression, and discrimination.