Orchid

The orchids are a large family of flowering plants, the Orchidaceae. They are herbaceous monocots.

| Orchidaceae Temporal range: Upper Cretaceous 80 mya – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

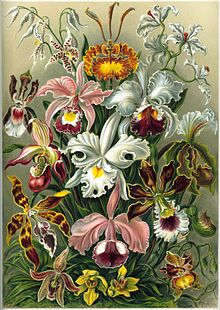

| From Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Orchidaceae |

| Subfamilies | |

There are between 100,000 and 126,000 species in 880 genera.[1][2] They make up between 6 and 11% of all seed plants. Orchids can be found in almost every country in the world except for Antarctica.[3]

People have grown orchids for a number of years. They grow orchids for show, for science, or for food (for example, vanilla).

Some orchids have very special ways of pollination. For example, the Lady's Slipper can trap insects and make them pollinate the flower. Another instance is the Austrian orchid, which grows underground and is pollinated by ants.

Many orchids are myco-heterotrophs, meaning their roots need fungi to break down organic material for them to absorb.

Distribution

changeColombia and Ecuador have many different species. The Brazilian Atlantic Forest has over 1500 species.[4] Other places with great variety are the mountains in the southern Himalayas in India and China. The mountains of Central America and southeastern Africa also have various species, especially on the island of Madagascar.

Ecuador has 3459 species, the greatest number recorded.[5] After Ecuador is Colombia, which has 2723.[2] Following Colombia are New Guinea (2717 species) and Brazil (2590 species).[5]

In warm places where there is much grass, or in places where there is dry savanna and rocky fields, orchids grow in the ground.[6][7] They have firm underground roots and sometimes have tubers to help protect themselves against cold or snow.[6] The tubers also help protect them against long droughts or fires.[6] The cold would freeze the roots if they were not protected to store the nutrients they need for blooming in the spring.

It is thought that some species are becoming extinct in the wild. This is mainly because people cut down forests for agriculture.[8][9][10]

Reproduction

changePollination

changeThe complex cross-pollination mechanisms were described by Charles Darwin in his 1862 book, The Fertilization of Orchids. Orchids have developed special pollination systems. The chances of being pollinated are often scarce, so orchid flowers usually remain receptive for very long periods, and most orchids deliver pollen in a single mass. Each time pollination succeeds, thousands of ovules can be fertilized. Catasetum, a genus discussed briefly by Darwin, actually launches its sticky pollinia with explosive force when an insect touches a seta (hair), knocking the pollinator off the flower.

Pollinators are often visually attracted by the shape and color of the flower. The flowers may produce attractive odors. In some extremely specialized orchids, such as the Eurasian genus Ophrys, the labellum is adapted to have a color, shape, and odour that attracts male insects via mimicry of a receptive female. Pollination happens as the insect attempts to mate with flowers.

Many neotropical orchids are pollinated by male orchid bees, which visit the flowers to gather the volatile chemicals they require to synthesize pheromonal attractants. Each type of orchid places the pollinia on a different body part of a different species of bee, so as to enforce proper cross-pollination. After pollination, the sepals and petals fade and wilt, but they usually remain attached to the ovary.

An underground orchid in Australia, Rhizanthella slateri, is never exposed to light and depends on ants and other terrestrial insects to pollinate it.

Some orchids mainly or totally rely on self-pollination, especially in colder regions where pollinators are rare.

Fruits and seeds

changeThe ovary typically develops into a capsule that splits along three or six longitudinal slits, while remaining closed at both ends. The ripening of a capsule can take two to 18 months.

The seeds are extremely small and very numerous, in some species over a million per capsule. After ripening, they blow off like dust particles or spores. They lack the food reserve called endosperm, so must have symbiosis with fungi to get nutrients to germinate. All orchid species rely on fungi to complete their lifecycles. As the chance for a seed to meet a fitting fungus is very small, only a minute fraction of all the seeds released grow into adult plants.

In cultivation, germination typically takes weeks. Horticultural techniques have been devised for germinating seeds on a nutrient-containing gel, so they do not need the fungus for germination.

The main component for the sowing of orchids in artificial conditions is agar. The substance is put together with some type of carbohydrate (actually, some kind of glucose) which provides qualitative organic feed. Such substance may be banana, pineapple, peach or even tomato puree or coconut milk. After the "cooking" of the agar agar (it has to be cooked in sterile conditions), the mix is poured into test tubes or jars where the substance begins to gel.

References

change- ↑ Stevens P.F. 2001 onwards. Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, version 9 Mobot.org

- ↑ "WCSP". World Checklist of selected plant families.

- ↑ Dressler, Robert L. (1981). The orchids: natural history and classification. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-87525-8.

- ↑ Guido Pabst & Fritz Dungs (1975) Orchidaceae Brasilienses vol. 1, Brucke-Verlag Kurt Schmersow, Hildesheim. ASIN: B0006CWVGI

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 R. Govaerts, M.A. Campacci (Brazil, 2005), D. Holland Baptista (Brazil, 2005), P.Cribb (K, 2003), Alex George (K, 2003), K.Kreuz (2004, Europe), J.Wood (K, 2003, Europe) World Checklist of Orchidaceae. The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Checklists by region and Botanical countries. Accessed on 26 December 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Wodrich, Karsten (1997). Growing South African Indigenous Orchids. CRC Press. ISBN 978-90-5410-650-0.

- ↑ "How to Care for Orchids | Neverland Blog". www.enterneverland.com. Archived from the original on 2022-07-17. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ↑ Averʹianov, L.V. (2003). Slipper Orchids of Vietnam: With an Introduction to the Flora of Vietnam. Timber Press (OR). ISBN 978-0-88192-592-0.

- ↑ Hansen, Eric (2001). Orchid Fever: A Horticultural Tale of Love, Lust and Lunacy. Methuen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-413-74750-1.

- ↑ Orchids of Borneo: Introduction and a selection of species. 1990. p. 27. ISBN 978-967-99947-3-5.

Other websites

change- "Orchidaceae at the Angiosperm Phylogeny Website". mobot.org. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- "Angiosperm Families - Orchidaceae Juss". delta-intkey.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2010.