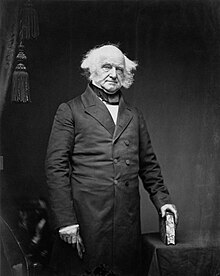

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren (December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States. He was the first president born after the United States Declaration of Independence, making him the first president who was born as a U.S. citizen after 1776.[1]

Martin Van Buren | |

|---|---|

| |

| 8th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1837 – March 4, 1841 | |

| Vice President | Richard Mentor Johnson |

| Preceded by | Andrew Jackson |

| Succeeded by | William Henry Harrison |

| 8th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1833 – March 4, 1837 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | John C. Calhoun |

| Succeeded by | Richard Mentor Johnson |

| 10th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 28, 1829 – May 23, 1831 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | Henry Clay |

| Succeeded by | Edward Livingston |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 5, 1782 Kinderhook, New York, USA |

| Died | July 24, 1862 (aged 79) Kinderhook, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican, Democratic, and Free Soil |

| Spouse(s) | Widowed Hannah Van Buren (daughter-in-law Angelica Van Buren was first lady) |

| Children | Abraham Van Buren John Van Buren Martin Van Buren (1812–55) Smith Thompson Van Buren |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

Van Buren was born in Kinderhook, New York, in 1782. Van Buren studied law by working for Francis Sylvester and later became a lawyer in 1803. In 1821 he was elected as a member of the United States Senate, representing New York.[2] President Andrew Jackson selected him as the Secretary of State in 1827. In 1832, he became vice President of the United States of America for Jackson, and in 1836, he became the 8th president of the United States.[2] During most of the time he was president, the economy was in very bad shape, and he was blamed for it. In fact, his critics called him Martin van Ruin.[3]

He was the first president to have been born a United States citizen,[4] since all of his predecessors were born British subjects before the American Revolution.[5]

Van Buren lost the next presidential election in 1840 to William Henry Harrison.[2] In 1848, he ran again to be president as a part of the Free Soil Party, but he did not win.[2] Van Buren died on July 24, 1862, of heart failure after suffering from an asthma attack, on his Lindenwald estate.

Early life

changeMartin Van Buren was born on December 5, 1782 in Kinderhook, New York, south of Albany. Van Buren was the third born of five children.[6] His father, Abraham Van Buren, was a farmer and a tavern owner.[7] His mother was Maria Hoes Van Buren, the granddaughter of a Dutch immigrant.[8] Martin Van Buren went to school at the Kinderhook Academy in the village where he lived. At Kinderhook Academy, he excelled in English and Latin.[9] Van Buren left the school when he was 14 years old.[1][10]

As a lawyer

changeIn 1796, Van Buren started working in the law office of Francis Sylvester, an attorney that worked in Kinderhook. He kept the office clean, copied documents and did other jobs. While he was working there, he learned about law. After six years under Sylvester, he spent a final year of apprenticeship in the New York City office of William P. Van Ness. Van Buren passed the New York State Bar Exam in 1803, and became a lawyer.[11]

After becoming a lawyer, Van Buren moved back to Kinderhook to work as an attorney with his half-brother, James J. Van Alen, in 1803.[12]

Five years later, Van Buren became the surrogate (legal officer) of Columbia County.[1][13] There was no fixed term of office. That is, Van Buren would be there until the opposition party was able to elect someone else in his place. Van Buren held the office about five years until he was removed on March 19, 1813.

Political career

changeVan Buren represented New York in the United States Senate from 1821 to 1828. He left the Senate to become the governor of New York in 1829. On March 5, 1829 after he became the governor, President Andrew Jackson made Van Buren the Secretary of State, so Van Buren was only the governor for two months.

From 1833 to 1837, he was the Vice President. (Jackson was still President at this time.) He was also a leading member of and gained much voting support by the Free Soil Party.

Just a few months after Van Buren became president, there was a financial crisis called the Panic of 1837. Van Buren believed in limited government, and did not respond in a way that many people wanted.[14] Even though it was probably Jackson's fault, many people blamed Van Buren for the economy becoming worse, and this made him less popular. He earned the nicknames "Little Magician" and the "Red Fox" for his cunning politics.

Personal life

changeVan Buren married Hannah Hoes, a cousin, on February 21, 1807.[1] They had five children together: Abraham, John, Martin Jr., Smith, and Winfield Scott.

Later life and Death

changeAfter the presidency, Van Buren remained active in politics. He was able to outlive the four presidents that came after him. In 1848, Van Buren ran for president again with the Free Soil Party. However, he lost that election. Van Buren remained critical of many things like the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. He supported Franklin Pierce in 1852, James Buchanan in 1856 and Stephen A. Douglas in 1860. As the American Civil War began in 1861, former president Franklin Pierce told Van Buren he should make a meeting with all the former presidents to try and make a solution. However, Van Buren said James Buchanan or Pierce should do it, but no one did. Van Buren supported the Union during the war.[15]

Martin Van Buren developed pneumonia in the fall of 1861 at the age of 78.[16] Due to this, he was bedridden. In July, 1862, Van Buren had a serious asthma attack and began to weaken.[17] Van Buren died on July 24, 1862, at his home in Kinderhook, New York, of heart failure.[12] He was 79 years old.

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Lazo, Caroline Evensen (2005). Martin Van Buren. Presidential leaders. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 9780822513940. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Martin Van Buren | The White House". whitehouse.gov. 2011 [last update]. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ↑ Ryan, Erica (July 20, 2013). "5 Memorable Nicknames and the Politicians They Stuck To". NPR. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ↑ NARA.gov Archived 2014-03-10 at the Wayback Machine, Martin Van Buren

- ↑ "Martin van Buren". Archived from the original on 2013-01-15. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- ↑ Jewell, Elizabeth (2005). U.S. presidents factbook. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 0375720731. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ↑ Buttre, Lillian C. (1877). The American portrait gallery. J.C. Buttre. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ↑ Waldrup, Carole Chandler (2004). More Colonial women: 25 pioneers of early America. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786418397. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Martin Van Buren--Reading 1". nps.gov. 2009 [last update]. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ↑ Quackenbos, George Payn (1864). Illustrated school history of the United States and the adjacent parts of America. D. Appleton & Company. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Martin Van Buren". nnp.org. 2009 [last update]. Archived from the original on April 23, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Shepard, Edward Morse (1888). Martin Van Buren. Houghton, Mifflin and Company. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ↑ "VAN BUREN, Martin - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. 2011 [last update]. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Digital History". digitalhistory.uh.edu. 2011 [last update]. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ↑ Niven, John (1983). Martin Van Buren: The Romantic Age of American Politics. New York, New York. p. 760. ISBN 978-0-945707-25-7. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Lamb, Brian; C-SPAN (2010). Who's Buried in Grant's Tomb?: A Tour of Presidential Gravesites. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1586488697. Retrieved April 3, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Doak, Robin Santos (2003). Martin Van Buren. Compass Point Books. ISBN 075650256X. Retrieved April 3, 2011.