User:Artesh-e Atash/Sandbox

Hi! I'm a student at Leiden University, currently working on Simple Wikipedia for a school project.

Sections and corrections/changes to add to the existing article on Abdullah Öcalan.

Abdullah Öcalan | |

|---|---|

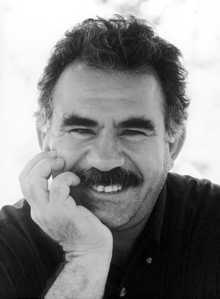

Öcalan in 1997 | |

| Born | Either 1946, 1947 or 1949 Ömerli, Republic of Türkiye |

| Nationality | Kurdish |

| Other names | Apo |

| Citizenship | Turkey |

| Occupation(s) | Founder and leader of the PKK, political theorist, writer |

| Political party | Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) |

| Other political affiliations | Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) |

| Criminal charges | Treason |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

| Spouse | Kesire Yıldırım (m. 1978) |

| Relatives |

|

Philosophy career | |

Notable ideas | Democratic confederalism, Jineology |

Abdullah Öcalan (/ˈoʊdʒəlɑːn/ OH-jə-lahn), also known as Apo ("Uncle in Kurdish), is a Kurdish political theorist. He is one of the founders and the current leader (even though he is in prison) of the militant Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which fights against the Turkish government for independence of Turkish Kurdistan. "Öcalan" means, in Turkish, "he who takes revenge".

The Turkish government considers him a terrorist. Turkey, the EU and the US, along with some other countries, have also listed the PKK as a terrorist organization.[1][2] However, there are people who think this label is controversial.[3][4][5]

During his twenties Öcalan became more aware of his Kurdish identity[6] and he started to embrace Marxist ideology.[7] After spending some time in prison he decided to form a new political party. In 1978 he founded the PKK with several others. Their mission statement was as follows: the liberation of the Turkish people can only be achieved through the liberation of the Kurdish people first.

In 1979 Öcalan fled to Syria with fellow PKK members. He remained based in Syria and Lebanon up until his arrest in 1999. In 1985 he led the PKK into the armed struggle against the Turkish state. Öcalan called this: "a war for the protection of existence".

The Syrian state was pressured by the US and Turkey to give Öcalan up. As a result of this Öcalan left Syria. He did not want to be responsible for starting a regional war. In 1999 he was kidnapped in Nairobi, Kenya and brought to Turkey.[8]

Öcalan was convicted of treason against the Turkish state and sentenced to death.[9] However his sentence was reduced to life imprisonment in 2002.[10] He has been imprisoned on İmralı island since 1999. For 10 years he was the only prisoner on the island. During his time in prison, Öcalan changed his mind about many of his political opinions.[11] He came up with the ideas of "Democratic Confederalism" and "Jineology", which were then accepted by the PKK and Rojava.[12]

Rojava continues to use many of his ideas in managing the territory they control in Syria.[13]

Early life

changeAbdullah Öcalan told Chris Kutschera in an interview that he does not know the exact year he was born in. This was also the last interview that Abdullah Öcalan gave before he was imprisoned. He did state that his year of birth should be 1947 or 1947.[14] However, his parents registered it as 1949. They may have had different reasons. For example, to give him a better chance when he would be called upon for the army.

He was born in the village of Ömerli, which is close to the city of Urfa.[15] There he lived with his father, mother and his six siblings. It is confirmed that Öcalan grandmother on his mother's side was a Turk. Öcalan himself claims that his mother was a Turk as well.[16]

Öcalan had to travel for an hour to his elementary school because there were none in his village. At these schools Turkish history and nationalism were taught strictly. So it was not unusual that Öcalan at first wanted to become a Turkish army officer. He tried out for the army entrance exam but failed. Instead he went to a high school in Ankara that trained pupils to work in state's land registry offices. He graduated in 1968 and began to work as a civil servant in Istanbul.[17]

During his time in Istanbul he also started studying law. It was during this time that he went to meetings organized by different Kurdish students groups.[18] Because of this he started to become more aware of his Kurdish identity, in Kurdish political problems.[19] However, he did not finish his studies at the university in Istanbul and went back to Ankara. Here Öcalan enrolled in the Faculty of Political Science in 1972.[20]

At the university of Ankara he started to embrace Marxist ideology. He became involved with leftist student groups.[21] In April 1972 he participated in the protests that followed the death of the Turkish revolutionary leader, Mahir Çayan. Öcalan was arrested during the protests. He spent seven months in prison.[22]

After Öcalan was released from prison, he immediately started making plans to create his own party. At first he wanted to work together with Turkish leftists groups that already existed, but they did not want to work with Öcalan. These groups were not concerned with the specific struggles of Kurds in Turkey. They believed that their revolution would already lead to the freedom of all people, including the Kurds. But Öcalan saw things differently: he viewed Kurdistan as a colony of Turkey that should be independent.[23] So he decided to start his own party. The first meeting took place in 1973. The organization adopted the statement of fellow member Kemal Pir as the framework for their party. It stated that the freedom of the Turkish people could only be achieved through the freedom of the Kurdish people first.[24]

Abdullah Öcalan, together with several others, founded the PKK in November of 1978 at a congress in the village of Fis[25] close to Diyarbakır. PKK stands for the "Kurdistan Workers' Party". Öcalan wrote the program of the party himself.[26]

During this time Turkey was politically unstable. It looked like the government could not guarantee basic safety for its own citizens. This resulted in a military coup in 1980. The army imposed martial law in the southeast of Turkey (Turkish Kurdistan). During this time the constitution was rewritten and ended up being very authoritarian. Between 1980 and 1983 the military often responded with violence against organized Kurds.[27] But Öcalan and fellow members of the PKK had actually already fled to Kobani in Syria in 1979, correctly predicting the military coup of 1980.[28]

PKK leadership

changeAbdullah Öcalan has been the only leader of the PKK since the founding of the party in 1978. He continued to be the official leader even after his imprisonment in 1999.[29]

From 1979 to 1998 Öcalan was based in Lebanon and Syria. He travelled a lot between these countries and worked together with the Palestinian Liberation Organization. He organized the political education of the PKK's followers, which he found more important than their military training at that time. Furthermore he was in charge of the foreign relations and diplomatic meetings of the PKK.[30]

Öcalan wrote a lot of works in his lifetime. His works after the coup of 1980 were mainly about:

- How to build an armed organization against fascism.

- How to fight Kurds working with the Turkish state.

- How to transform Kurdish militants in freedom fighters.[31]

In August of 1985 the PKK attacked several state security forces.[32] This was the beginning of the armed conflict between the Turkish state and the PKK. Even after the military coup ended, the armed struggle of the PKK against the Turkish state continued. Öcalan referred to the armed struggle as "a war for the protection of existence". It was during this time that Öcalan came to believe that the PKK needed to review their strategies and solutions. His works of that time were mainly about this topic. In these works he brought up the idea of a radical form of democracy. This radical form would free Kurds, women and other opressed groups. This became the root of Democratic Confederalism.

Later on in the 1990s Öcalan wanted to start a conversation with the Turkish state. He tried to do this several times but it was prevented several times. The PKK believed NATO was behind this.

Eventually Abdullah Öcalan had to leave Syria in October of 1998 because of military and diplomatic pressure on the Syrian government by the US. On top of that, Turkey threatened to start a war against Damascus. Öcalan left Syria voluntarily because he did not want to be responsible for starting a regional war. A journey through multiple European countries led him to Rome. He was arrested here. However, the Italian government did not hand him over to Turkey, and he was released. Öcalan then made plans to go to South Africa. However, on the 15th of February he was kidnapped outside the Greek embassy in Nairobi, Kenya and brought back to Turkey.[33]

Arrest and Imprisonment

changeOn 15 February 1999 Öcalan was arrested by Turkish agents in Kenya.[34] He had been on his way to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport from the Greek embassy in Nairobi. The Turkish agents were helped by the CIA, and possibly Mossad.[35] Details of his capture are still unclear. Costoulas, the Greek ambassador who had protected Öcalan, said that his own life was in danger after the operation.[36] Öcalan's arrest sparked many protests by Kurds around the world. The biggest protests were in Turkey, Iran and Germany. Kurdish protesters stormed the Israeli Consulate in Berlin because they blamed Mossad for Öcalan's arrest. Three of them were shot and killed by Israeli guards.[37][38]

Öcalan was brought to İmralı island. He was charged with treason and separatism on February 23rd of 1999. He was tried before a military court on the island from May 31st of 1999. Three Dutch lawyers came to represent him, but they were sent back to the Netherlands after the Turkish government accused them of "acting like PKK militants".[39] Öcalan ended up being represented by the Asrın Law Office. Despite his lawyers' efforts, Öcalan was sentenced to death on the 29th of June 1999.[9] His appeal was rejected in November, but even so the sentence would be suspended while a review by the European Court of Human Rights took place. When Turkey eventually scrapped the death sentence in 2002, Öcalan's sentence was reduced to life in prison.[10] Turkey had abandoned the death penalty in August 2002 as part of the process towards joining the European Union.[40]

Between 1999 and 2009 Öcalan was the only prisoner on İmralı island. While in prison, Öcalan found a much time to read, think and write. As a result of this he changed many of his views, including coming to support peaceful diplomatic solutions to the Turkish-Kurdish conflict rather than violence.[41] One of the authors who greatly influenced Öcalan's thinking during his time in prison is Murray Bookchin, an American writer whose idea of "Libertarian municipalism" would lead Öcalan to develop Democratic Confederalism.[12]

In 2009 five other prisoners were brought to İmralı island. Four of these were also PKK members, the last was a member of the Communist Party of Turkey.[42] No information on the well-being of these men has been available since 2021.[43]

In 2023, media said that his lawyers have not seen Öcalan for 2 years. Furthermore, the lawyers are not sure if he still is being kept on Imrali (island).[44] Turkey has also denied Human Rights Organizations access to Öcalan many times.[43]

Ideological Beliefs

changeBefore his imprisonment, the beliefs of Öcalan and the PKK were largely based on Marxism and Marxist-inspired decolonization movements from around the world.[45] The idea that Kurdistan was a colony of Turkey that deserved independence was central to their ideology.[46] The PKK fought the Turkish government with this goal of independence in mind.

However, during his time in prison Öcalan moved away from Marxism.[11][47] He came up with his own ideology. Öcalan's new ideology is called "Democratic Confederalism". He also refers to it as a "democracy without a state". Öcalan believes that the capitalist nation-state is always oppressive, and that it would not make sense for the Kurds to make a new nation-state right after they become independent from another. In other words, he does not like centralism.[48] Instead, he describes a model of state organization in which towns rule themselves. They do this through their own local councils. The council members are chosen by the townspeople. Sometimes the local councils will organize large meetings with councils from other towns to talk about bigger problems, but there will not be a central government.[49] Each town will also be a military unit, so they can defend themselves when they have to. Direct democracy, feminism and the protection of nature are central pillars of Democratic Confederalism.[50] Öcalan believes women should be involved at every level of society, including politics. He says no society is free unless the women are free.[51][52][53] Öcalan calls his uniquely Middle-Eastern form of feminism "Jineology".

The PKK has since accepted Öcalan's new ideas. They made it part of their beliefs.[54] Also, starting in 2012, the Kurds of Rojava put the ideas of Democratic Confederalism into practice in northeast Syria.[13][12]

References

change- ↑ "Council Decision (CFSP) 2024/332 of 16 January 2024 updating the list of persons, groups and entities covered by Common Position 2001/931/CFSP on the application of specific measures to combat terrorism, and repealing Decision (CFSP) 2023/1514". EUR-Lex. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ↑ "Foreign Terrorist Organizations". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ↑ tagesschau.de. "EU-Gericht: PKK zu Unrecht auf EU-Terrorliste". tagesschau.de (in German). Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ↑ Bodette, Meghan (2018). "It's time to delist the PKK as a terror organisation". Progressive International. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ Rubin, Michael (2020). "US Should Follow Belgium's Lead and End PKK Terror Designation". American Enterprise Institute - AEI. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ Kiel, Stephanie L. (2011). Understanding the power of insurgent leadership: A case study of Abdullah Öcalan and the PKK. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. p. 22.

- ↑ Marcus, Aliza (2007). Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. New York: New York: New York University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 08147-9611-7.

- ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). The Art of Freedom : A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 9781629637815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 Hacaoglu, Selcan (1999). "Öcalan sentenced to death - The Argus Press". news.google.com. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Archives, L. A. Times (2002-10-04). "Kurd's Death Sentence Commuted to Life Term". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Novellis, Andrea (2018). "The Rise of Feminism in the PKK: Ideology or Strategy?" (PDF). Zanj: The Journal of Critical Global South Studies. 2: 115 – via ScienceOpen.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Writings of Obscure American Leftist Drive Kurdish Forces in Syria". Voice of America. 2017-01-16. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Shahvisi, Arianne (2023-06-09). "Beyond orientalism: exploring the distinctive feminism of democratic confederalism in Rojava". Geopolitics. 26 (4): 1–25. doi:10.1080/14650045.2018.1554564'].

- ↑ "Abdullah Ocalan's Last Interview". web.archive.org. 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ↑ Zartman, Jonathan K. (2020). Conflict in the modern Middle East: an encyclopedia of civil war, revolutions, and regime change. Santa Barbara: California: Santa Barbara: California: ABC-CLIO. p. 219. ISBN 979-82-16-06477-0.

- ↑ Marcus, Aliza (2007). Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. New York: New York University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-8147-9611-7.

- ↑ Marcus, Aliza (2007). Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. New York: New York University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 0-8147-9611-7.

- ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). The Art of Freedom A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. p. 69. ISBN 9781629637815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kiel, Stephanie L. (2011). Understanding the power of insurgent leadership: A case study of Abdullah Öcalan and the PKK. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. p. 22.

- ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). The Art of Freedom : A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. p. 69. ISBN 9781629637815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Marcus, Aliza (2007). Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. New York: New York University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 08147-9611-7.

- ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). The Art of Freedom : A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. p. 69. ISBN 9781629637815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kiel, Stephanie L. (2011). Understanding the power of insurgent leadership: A case study of Abdullah Öcalan and the PKK. ProQuest Dissertation Publishing. pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). Template:The Art of Freedom : A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. p. 69. ISBN 9781629637815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley,, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). The Art of Freedom : A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. p. 69. ISBN 9781629637815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Zartman, Jonathan K. (2020). Conflict in the Modern Middle East : An Encyclopedia of Civil War, Revolutions, and Regime Change. Santa Barbara: California: Santa Barbara: California: ABC-CLIO. p. 69. ISBN 979-82-16-06477-0.

- ↑ Kiel, Stephani L. (2011). Understanding the power of insurgent leadership: A case study of Abdullah Öcalan and the PKK. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). Template:The Art of Freedom : A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. p. 69. ISBN 9781629637815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kiel, Stephanie L. (2011). Understanding the power of insurgent leadership: A case study of Abdullah Öcalan and the PKK. ProQuest Dissertations Publisher. p. 1.

- ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). The Art of Freedom : A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. p. 69. ISBN 9781629637815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). The Art of Freedom : A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9781629637815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kiel, Stephanie L. (2011). Understanding the power of insurgent leadership: A case study of Abdullah Öcalan and the PKK. ProQuest Dissertation Publishing. p. 24.

- ↑ Guneser, Grubačić, Lilley, Havin, Andrej, Sasha (2020). The Art of Freedom : A Brief History of the Kurdish Liberation Struggle. Oakland: Oakland: PM Press. pp. 70–71.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gilbert, Geoff (1999). "The Arrest of Abdullah Öcalan". Leiden Journal of International Law. 12 (3): 565–574.

- ↑ Weiner, Tim (1999-02-20). "U.S. Helped Turkey Find and Capture Kurd Rebel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ Ünlü, Ferhat (17 July 2007). "Türkiye Öcalan için Kenya'ya para verdi". Sabah (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 12 January 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ↑ Cohen, Roger (1999-02-18). "3 KURDS SHOT DEAD BY ISRAELI GUARDS AT BERLIN PROTEST". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ Hooper, John; Kundnani, By Hans (1999-02-18). "Military action and three deaths after Ocalan's capture". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ "Washingtonpost.com: Turkey Celebrates Capture of Ocalan". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ Ap (2002-08-02). "Turkey abolishes death penalty | The Independent". The Independent. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ "PKK-leider Öcalan roept op tot 'diepgaande verzoening' in Turkije". nos.nl (in Dutch). 2019-05-06. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ "PKK leader Ocalan gets company in prison - UPI.com". UPI. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 medya, eylul (2024-03-19). "Swiss Parliament urged to address Öcalan's isolation on İmralı Island". Medya News. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ Johansen, Peter M. [Being kept in Erdogan's dungeon] Holdes i Erdogans fangehull. 2023-04-17. Klassekampen. Pages 14 and 15

- ↑ Jongerden, Joost (2017-10-01). "Gender equality and radical democracy: Contractions and conflicts in relation to the "new paradigm" within the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK)". Anatoli. De l’Adriatique à la Caspienne. Territoires, Politique, Sociétés (8): 233–256. doi:10.4000/anatoli.618. ISSN 2111-4064.

- ↑ Kiel, Stephanie L. (2011). Understanding the power of insurgent leadership: A case study of Abdullah Öcalan and the PKK. ProQuest Dissertation Publishing. pp. 22–23.

- ↑ "Bookchin, Öcalan, and the Dialectics of Democracy | New Compass". web.archive.org. 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ↑ Öcalan, Abdullah (2017). The Political Thought of Abdullah Öcalan: Kurdistan, Woman's Revolution and Democratic Confederalism. London: Pluto Press. pp. 30–56. ISBN 9780745399768.

- ↑ Öcalan, Abdullah (2011). Democratic Confederalism. London: Transmedia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9567514-2-3.

- ↑ Öcalan, Abdullah (2011). Democratic Confederalism. London: Transmedia Publishing Ltd. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-941012-47-9.

- ↑ Öcalan, Abdullah (2017). The Political Thought of Abdullah Öcalan: Kurdistan, Woman's Revolution and Democratic Confederalism. London: Pluto Press. pp. 57–96. ISBN 9780745399775.

- ↑ Käser, Isabel (2021). The Kurdish women's freedom movement: gender, body politics and militant feminities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-316-51974-5.

- ↑ Argentieri, Benedetta (3 February 2015). "One group battling Islamic State has a secret weapon – female fighters". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Enzinna, Wes (2015-11-24). "A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS' Backyard". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-05-23.