Separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine that existed in the United States for 58 years. It was based on the United States Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson. Here the Court ruled that racial segregation was not in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as long as the racially separate facilities were equal.[1] The Court also said segregation was not discrimination.[2] Segregation in public accommodations, transportation and schools was legally justified by Plessy until it was overturned in 1954 by Brown v. Board of Education.[1]

Background

changeAfter the American Civil War, the Republican controlled Congress passed three amendments to the Constitution called the Reconstruction Amendments.[3] The first was the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution which abolished slavery in the United States.[3] The second was the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution which provided equal protection of the laws to all citizens.[3] The third was the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution that gave voting rights to African American men.[3]

After the passage of the reconstruction amendments, things began to get worse for black people in the South. Many whites would not accept the new changes.[4] The economy in the south was stagnant and taxes were high. There was a good deal of corruption which was made worse by carpetbaggers from the north and southern supporters of reconstruction called scalawags.[4] Out of fear and hatred, white supremacy groups such as the Ku Klux Klan were born.[4] Through the use of violence including lynching, rape, murder and terrorism, they sought to control African Americans and keep them from using their new rights.

Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1875.[5] It guaranteed African Americans equal treatment in public accommodations, public transportation, and to prevent being excluded from jury duty. The bill was passed by the 43rd United States Congress and signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1875. Several years later, the Supreme Court ruled in Civil Rights Cases (1883) that sections of the act were unconstitutional.[5] The Court's reasoning was the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited discrimination by states not by individuals. As a result Congress could not protect against individual cases of discrimination.[5]

Plessy v. Ferguson

changeFlorida was the first to pass a law requiring railroads to provide “equal but separate accommodations for the white, and colored, races”.[6] Soon, Texas, Mississippi and other states had the same or similar laws. In 1890, when Louisiana passed a similar law, blacks began resisting. In 1892 it was agreed Homer Plessy would challenge the laws in order to form a test case. Plessy "passed" for white[a] and while riding on an East Louisiana train in the "white section" announced he was black and refused to move to the "colored" section.[7] Plessy was arrested and 1896 his case reached the Supreme Court. The case was Plessy v. Ferguson, Fergusson being the name of the Judge who first ruled against him in the New Orleans Criminal District Court.[7]

In 1896, the Supreme Court heard the case. Plessy's lawyers argued Louisiana's Separate Car Act violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. The Court, in a 7-1 decision decided against Plessy and that the law was constitutional. Writing the majority opinion, Justice Henry Brown wrote:

"A statute which implies merely a legal distinction between the white and colored races -- has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races. ... The object of the Fourteenth Amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either."[8]

The lone dissenter, Justice John Harlan, saw terrible consequences in the judicial opinion rendered by the court. He wrote:

"Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. ... The present decision, it may well be apprehended, will not only stimulate aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens, but will encourage the belief that it is possible, by means of state enactments, to defeat the beneficent purposes which the people of the United States had in view when they adopted the recent amendments of the Constitution."[8]

The problem with Plessy was that separate was almost always never equal. The public schools and other facilities designed for blacks were always inferior.[8]

Jim Crow era

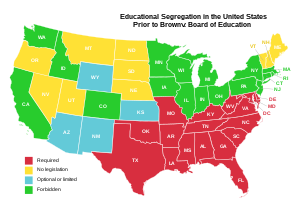

changeBeginning in 1890, Southern Democrats began to pass state laws that took away the rights African Americans had gained. These racist laws became known as Jim Crow laws.[b] Plessy caused Jim Crow laws to go unchallenged by the federal government for 58 years.[8] They included laws that made it impossible for blacks to vote. Since they could not vote, blacks also could not be on juries.[9] Other laws required racial segregation so blacks could not go to the same schools, restaurants or hospitals as whites. They could not use the same bathrooms or drink from the same drinking fountains. They could also not sit in front of whites on busses or trains. Many southern Christian ministers taught that whites were the chosen people and blacks were cursed by God.[10] Lynchings were designed to instill fear in blacks and keep them in their place. Between 1882 and 1968, 3,440 black men and women were lynched.[10] Others were burned at the stake, castrated, beaten or murdered.[10] The Jim Crow era began to end after the Supreme Court’s unanimous Brown v. Board of Education decision overruled Plessy.

Notes

change- ↑ Plessy was of mixed racial heritage and had one grandfather who was African, making him one-eighth black.[7] He and members of his family looked white.[7]

- ↑ They were called "Jim Crow" from an 1828 minstrel show song "Jump Jim Crow".[5] It was usually performed by white actors in blackface (black face paint) and showed blacks as inferior and ignorant people.[5]

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Separate But Equal: The Plessy v. Ferguson Case". History Matters. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ "Separate but Equal: The Law of the Land". Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Slavery by Another Name; Reconstruction Amendments". PBS. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Reconstruction: Rebuilding the Old Order". US History.org. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "The birth of "Jim Crow"". UNC School of Education. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ Kim J. Askew (1 November 2013). "The Supreme Court rejects the separate but equal doctrine". American Bar Association. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Homer Plessy Biography". Bio/A&E Television Networks, LLC. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow: Plessy v. Ferguson". Educational Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), pp. 121, 235

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Jim Crow Museum". Ferris State University. Retrieved 2 April 2016.