Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War was a war fought between Spain and the United States in 1898, partly because many people in Cuba, one of the last parts of the Spanish Empire, wanted to become independent. Many Americans also wanted their country to get a colonial empire.

| Spanish–American War[b] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Philippine Revolution and the Cuban War of Independence | |||||||||

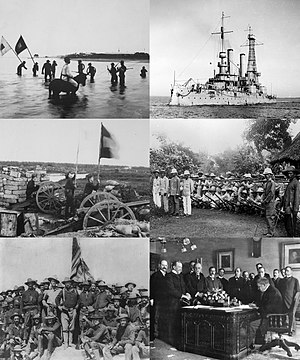

(clockwise from top left)

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Other leaders Other leaders Other leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Total: 300,000[5] |

Total: 339,783[9]

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

American: |

Spanish: | ||||||||

|

The higher naval losses may be attributed to the disastrous naval defeats inflicted on the Spanish at Manila Bay and Santiago de Cuba.[14] | |||||||||

Spain lost the sea war and so had to give up Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. All of those colonies, except for Cuba, became American colonies after the war, and Cuba became an independent country but with much US influence.

Background

changeFollowing reports of Spain abusing and killing Cubans, the United States sent warships to Cuba. Spain was losing control of Cuba and so put Cubans into concentration camps. The US sent ships to Cuba to try to make Spain to give up Cuba. The USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor, which killed about 260 people on board.

"Remember the Maine" became a common wartime saying. US newspapers blamed Spain for the explosion without proof. Spain tried to avoid going to war, but pressure from US newspapers, which had "yellow journalism," and from ordinary people persuaded the US government to go to war. Some Americans wanted Cuba to become independent, but others hoped that the US could build a colonial empire overseas since many European countries had already done so.

Course of war

changeVolunteers throughout the country signed up for the war. Future US President Theodore Roosevelt raised troops and became famous by leading the Rough Riders during the Battle of San Juan Hill.

In a large naval battle in Manila Bay, an American fleet, commanded by George Dewey, destroyed the Spanish fleet.

Ground battles took place in Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Aftermath

changeThe US won the war and soon began to occupy and to take control of the colonies after Spain had surrendered. Almost 400 American soldiers had died during the fighting, but more than 4000 Americans died from diseases such as yellow fever, typhoid, and malaria.

The Treaty of Paris was signed on December 10, 1898 by the United States and Spain. The United States now controlled Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.[17] Later, it also got the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, and Cuba became an independent country but with much US influence.

Notes

changeReferences

change- ↑ Louis A. Pérez (1998), The war of 1898: the United States and Cuba in history and historiography, UNC Press Books, ISBN 978-0807847428, retrieved October 31, 2015

- ↑ Benjamin R. Beede (1994), The War of 1898, and US interventions, 1898–1934: an encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0824056247, retrieved October 31, 2015

- ↑ Virginia Marie Bouvier (2001), Whose America?: the war of 1898 and the battles to define the nation, Praeger, ISBN 978-0275967949, retrieved October 31, 2015

- ↑ Thomas David Schoonover; Walter LaFeber (2005), Uncle Sam's War of 1898 and the Origins of Globalization, University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 978-0813191225, retrieved October 31, 2015

- ↑ Dyal, Carpenter & Thomas 1996, p. 21-22.

- ↑ Clodfelter 2017, p. 256.

- ↑ Clodfelter 2017, p. 308.

- ↑ Karnow 1990, p. 115

- ↑ Dyal, Carpenter & Thomas 1996, p. 20.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "America's Wars: Factsheet." Archived July 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine US Department of Veteran Affairs. Office of Public Affairs. Washington DC. Published April 2017.

- ↑ Marsh, Alan. "POWs in American History: A Synoposis" Archived August 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. National Park Service. 1998.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Clodfelter 2017, p. 255.

- ↑ See: USS Merrimac (1894).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Keenan 2001, p. 70.

- ↑ Clodfelter describes the U.S. capturing 30,000 prisoners (plus 100 cannons, 19 machine guns, 25,114 rifles, and various other equipment) in the Oriente province and around Santiago. He also states that the 10,000-strong Puerto Rican garrison capitulated to the U.S. after only minor fighting.

- ↑ Tucker 2009, p. 105.

- ↑ "Military Map, Island of Puerto Rico". World Digital Library. 1898. Archived from the original on August 19, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

Sources

change- American Peace Society (1898), The Advocate of Peace, American Peace Society, retrieved January 22, 2008

- {{citation|last=Bailey|first=Thomas Andrew|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dnRGAAAAMAAJ%7Ctitle=The[permanent dead link] American Pageant: A History of the Republic|year=1961|publisher=Heath|access-date=August 18, 2020}

- Baycroft, Timothy; Hewitson, Mark (2006), What is a nation?: Europe 1789–1914, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199295753, retrieved October 31, 2015

- Beede, Benjamin R., ed. (1994), The War of 1898 and US Interventions, 1898–1934, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0824056247, retrieved October 31, 2015. An encyclopedia

- Bergad, Laird W. (1978). "Agrarian History of Puerto Rico, 1870–1930". Latin American Research Review. 13 (3): 63–94. doi:10.1017/S0023879100031290. S2CID 133521213.

- Botero, Rodrigo (2001), "Ambivalent embrace: America's troubled relations with Spain from the Revolutionary War to the Cold War", Contributions to the study of world history, vol. 78, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0313315701, retrieved August 18, 2020

- Brune, Lester H.; Burns, Richard Dean (2003), "Chronological History of US Foreign Relations: 1607–1932", Volume 1 of Chronological History of US Foreign Relations, Richard Dean Burns (2 ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415939140

- Campbell, W. Joseph (2001), Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0275966867, retrieved August 18, 2020

- Carr, Raymond (1982), Spain, 1808–1975, Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0198221289[permanent dead link]

- Carreras, Albert; Tafunell, Xavier (2004), Historia económica de la España Contemporánea, Crítica, ISBN 978-8484325024

- Cervera Y Topete, Pascual. Office of Naval Intelligence War Notes No. VII: Information From Abroad: The Spanish–American War: A Collection of Documents Relative to the Squadron Operations in the West Indies, Translated From the Spanish. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin (2007), USS Olympia: Herald of Empire, Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1591141266, retrieved October 31, 2015

- Dupuy, Trevor Nevitt; Johnson, Curt; Bongard, David L. (1992), The Harper encyclopedia of military biography, HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0062700155, retrieved March 27, 2016

- Dyal, Donald H; Carpenter, Brian B.; Thomas, Mark A. (1996), Historical Dictionary of the Spanish American War, Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0313288524, retrieved August 18, 2020

- Foreman, John (F.R.G.S.) (1906). The Philippine Islands: A Political, Geographical, Ethnographical, Social and Commercial History of the Philippine Archipelago, Embracing the Whole Period of Spanish Rule, with an Account of the Succeeding American Insular Government. C. Scribner's sons. (full text available here Archived August 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine)

- Gatewood, Willard B. (1975), Black Americans and the White Man's Burden, 1898–1903, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 978-0252004759

- Gaudreault, André (2009), American cinema, 1890–1909: themes and variations, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 978-0813544434, retrieved August 18, 2020

- Hendrickson, Kenneth E., Jr. (2003), The Spanish–American War, Greenwood, ISBN 978-0313316623, retrieved August 18, 2020

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). short summary - Karnow, Stanley (1990), In Our Image, Century, ISBN 978-0712637329

- Keenan, Jerry (2001). Encyclopedia of the Spanish–American & Philippine–American Wars. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576070932.

- Lacsamana, Leodivico Cruz (2006), Philippine history and government, Phoenix Pub. House, ISBN 978-9710618941, retrieved August 18, 2020

- Levy, Jack S.; Thompson, William R. (2010), Causes of War, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-1405175593, retrieved October 31, 2015

- Millis, Walter (1979), The martial spirit, Ayer Publishing, ISBN 978-0405118661, retrieved October 31, 2015

- Montoya, Arthur (2011), America's Original Sin: Absolution & Penance, Xlibris Corporation, ISBN 978-1462844340, retrieved October 31, 2015Articles lacking reliable references[self-published source]

- Negrón-Muntaner, Frances (2004), Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture, NYU Press, ISBN 978-0814758182

- Nofi, Albert A. The Spanish–American War, 1898. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Combined Books, Inc., 1996. ISBN 0938289578

- Offner, John L. (1992), An Unwanted War: the Diplomacy of the United States and Spain over Cuba, 1895–1898

- Offner, John L. (2004), "McKinley and the Spanish–American War", Presidential Studies Quarterly, 34 (1): 50–61, doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2004.00034.x, ISSN 0360-4918

- Parker, John H. (2003), The Gatlings at Santiago, Indypublish.com, ISBN 978-1404381377, archived from the original on March 29, 2006, retrieved January 1, 2006

- Pérez, Louis A. Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003. Print[ISBN missing]

- Pérez, Louis A. (2008), Cuba in the American Imagination: Metaphor and the Imperial Ethos, UNC Press Books

- Pérez, Louis A. (1998), The war of 1898: the United States and Cuba in history and historiography, UNC Press Books, ISBN 978-0807847428, retrieved October 31, 2015

- Rogers, Robert F. (1995), Destiny's Landfall: A History of Guam (illustrated ed.), University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0824816780, retrieved October 31, 2015

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1899), "I. Raising The Regiment", The Rough Riders, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, archived from the original on February 6, 2009, retrieved January 14, 2009

- Smithsonian Institution (2005), The Price of Freedom: Americans at War – Spanish American War, National Museum of American History (US), ISBN 978-0974420233

- Santamarina, Juan C. "The Cuba Company and the Expansion of American Business in Cuba, 1898–1915". The Business History Review 74.01 (Spring 2000): 41–83. Print

- Saravia, José Roca de Togores y; Garcia, Remigio (2003), Blockade and Siege of Manila in 1898, National Historical Institute, ISBN 978-9715381673, retrieved December 30, 2017

- Smith, Mark. "The Political Economy of Sugar Production and the Environment of Eastern Cuba, 1898–1923". Environmental History Review 19.04 (Winter 1995): 31–48. Print

- Smythe, Ted Curtis (2003), The Gilded Age press, 1865–1900, Praeger, ISBN 978-0313300806, retrieved October 31, 2015

- Tone, John Lawrence. War and Genocide in Cuba 1895–1898 (2006) online review Archived January 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Trask, David F. (1996), The war with Spain in 1898, U of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0803294295, retrieved October 31, 2015

- Tucker, Spencer (2009), The Encyclopedia of the Spanish–American and Philippine–American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1851099511, retrieved September 14, 2017

- Wionzek, Karl-Heinz (2000), Germany, the Philippines, and the Spanish–American War: four accounts by officers of the Imperial German Navy, National Historical Institute, ISBN 978-9715381406, retrieved October 31, 2015

- Wolff, Leon (1961), Little Brown Brother: How the United States Purchased and Pacified the Philippine Islands at the Century's Turn, Wolff Productions, ISBN 978-1582882093, retrieved October 31, 2015