Piano

The piano is an acoustic, keyboard and stringed musical instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboard, which is a row of keys (small levers) that the performer presses down or strikes with the fingers and thumbs of both hands to cause the hammers to strike the strings. It was invented in Italy by Bartolomeo Cristofori around the year 1700 (the exact year is uncertain).

A grand piano (left) and an upright piano (right) | |

| Keyboard instrument | |

|---|---|

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 314.122-4-8 (Simple chordophone with keyboard sounded by hammers) |

| Inventor(s) | Bartolomeo Cristofori |

| Developed | Early 18th century |

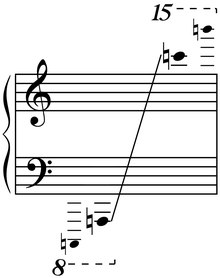

| Playing range | |

| |

| Musicians | |

| Pianists (Lists of pianists) | |

History

changeThe piano has been an extremely popular instrument in Western classical music since the late 18th century. The piano was invented by Bartolomeo Cristofori of Padua, Italy. He made his first piano in 1709. It developed from the clavichord which looks like a piano but the strings of a clavichord are hit by a small blade of metal called a “tangent”.[1] In the piano the strings are hit by a block of wood called a hammer. The early keyboarded instruments, such as the clavichords, harpsichords and organs that were used at that time, had a much shorter keyboard than they do today. Gradually the keyboard became longer until it had the 88 notes (7 octaves plus three notes) of the modern piano.

At first the instrument was called the “fortepiano”. This means “loud-soft” in Italian. It was given this name because it could be played either loudly or softly, depending on how hard the note was hit (the harpsichord could not do this, and the clavichord could only make a tiny difference between louder and softer). Later this name changed to “pianoforte”. This is normally shortened to “piano”. The word “fortepiano” is sometimes used to describe the pianos of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In some languages, such as Russian, “fortepiano” is the normal word for a piano.

Although the piano was invented at the beginning of the 18th century, it was not until 50 years later that it started to become popular. The first time the piano was played in a public concert in London was in 1768 when it was played by Johann Christian Bach.[2] The upright piano was invented in 1800 by John Isaac Hawkings. Seven years later T. Southwell invented “over-stringing”. This means that the strings for the low notes go diagonally across the soundboard so that they can be longer and make a much bigger sound.

The early pianos had strings that were fastened to a frame made of wood. They were not very heavy, but they were not very strong or loud, so they could not be heard very well in a big concert hall. In 1825 the cast-iron frame was invented in America. This made the piano much stronger so that it could make a bigger sound and the strings were not likely to break.

One of the most known fortepiano builders was Johann Andreas Stein from Augsburg, Germany. Stein developed the "Viennese" action, popular on Viennese pianos up to the mid-19th century.[3] Another important Viennese piano maker was Anton Walter.[4] Mozart’s own Walter fortepiano is presently at the Mozart Museum in Salzburg, Austria. Haydn also owned Walter piano,[5] and Beethoven expressed a wish to buy one.[6] The most famous early-romantic piano maker was Conrad Graf (1782–1851), who made Beethoven's last piano.[7] His instruments were played by Chopin, Mendelssohn and Schumann. Johannes Brahms had preferred pianos by Johann Baptist Streicher.[8] The English piano school builders included Johannes Zumpe, Robert Stodart and John Broodwood. Prominent piano makers among the French during the era of the fortepiano included Erard, Pleyel (Chopin’s favorite maker)[9] and Boisselot (Liszt’s favorite).[10]

The production of this older type of instrument had stopped in the end of the 19th century. In the second half of the 20th century people started to be more interested in period instruments, including harpsichord and fortepiano. Some of the more known fortepiano builders included in this 20th-century fortepiano revival have been Philip Belt, Margaret F. Hood, Christopher Clark and Paul McNulty.

Piano parts

changeA piano has a keyboard with white keys and black keys. When a key is pressed down, the damper comes off the string and a hammer hits the string. It hits it very quickly and bounces off so that the string is free to vibrate and make a sound. Each key is a level that makes a hammer inside the piano hit a string inside, producing a sound. Each string has a different length and so produces-a different note. When the player takes their finger off the key the damper falls back onto the string and the sound stops. The strings are stretched very tightly across the frame, passing over a bridge on the way. The bridge touches the soundboard. This means that the vibrations are sent to the soundboard. The soundboard is a very important part of the piano. If it is damaged the piano will not make a sound.

The mechanism which makes the hammer bounce off the string very quickly is called the “escapement”. In 1821 Sebastian Erard invented a kind of double escapement. This made it possible to repeat the note very quickly. The hammer only touches the string for about one thousandth of a second. The hammers are covered with felt which is a mixture of wool, silk and hair.

Pedals

changeAt the bottom of every modern piano, there are at least two pedals, which are levers that the pianist presses down with his or her feet to change the sound. Many pianos have three pedals, but a few have even more. Each pedal changes the sound in a different way.

- The damper pedal (also called the sustain pedal) is the pedal on the right, and the one that is used most often. For this reason, it is often called just "the pedal". It is pressed with the pianist's right foot, and makes the dampers (which look a bit like the hammers) that usually rests on the strings come off, so the strings are free to vibrate. As long as the pianist holds this pedal down, the notes he plays will keep on sounding even when he takes his fingers off the keys. Some other strings will also vibrate very lightly (this is called “sympathetic vibration”), which makes the sound smoother and richer. Pianists have to learn how to use this pedal well. This will depend on such things as the style of the music, the size of the piano, the size and the acoustics of the room in which the instrument is in.

- The soft pedal (also called the una corda pedal) is the pedal on the left, and is pressed with the pianist's left foot. As its name suggests, this pedal makes the notes sound quieter. On a grand piano, the whole keyboard and action shift a bit to the left so that the hammers only hit two strings instead of three. The soft pedal is usually used only in classical music and is normally kept down for the whole of a piece or a section of a piece.

- On pianos with three pedals, the pedal in the middle does different things on a grand and upright piano. On a grand piano, it is the sostenuto pedal, and is pressed with the pianist's left foot. Like the right pedal, it keeps the sound going, but only on the notes that are being played at the moment when the middle pedal is pressed down. This makes it possible to keep one chord going while playing other notes that will not carry on. All concert grand pianos have a sostenuto pedal, and some modern upright pianos do as well. The middle pedal on some upright pianos is not a sostenuto pedal at all, but a practice pedal. It places a piece of cloth in front of the strings, making the sound very quiet so that a pianist can practice without disturbing other people. The practice pedal can usually be pressed down and put in a slot so that it will stay in place.

Pedal marks in music

changeThe damper pedal is the most important pedal, and so many composers often write down in a piece of music when the pianist should press and when he or she should let go of the damper pedal. In most classical music, there is a sign that says Ped. where the pedal should be pressed, and one that looks like an asterisk where the pedal should be let go. Pedal marks can also appear as a straight line under the staff. Often, the pianist will let go of the pedal and press it again right away; this is called changing pedal. Sometimes, the music will simply say con pedale, which in Italian means with pedal. It means that the damper pedal should be used, but the pianist should know when to change the pedal.

Another sign, which tells a pianist to press the soft pedal is una corda, (Italian for one string). It is held down until another sign, tre corde (meaning three strings), appears, telling the pianist to let go of the soft pedal. In early pianos, it was possible to press the pedal a little way so that the hammers hit two strings, then press it further so that they hit only one string.

There is no sign for the sostenuto pedal, so it is up to the pianist on whether to use it in a specific piece of music.

Famous piano composers

changeOnce the piano became popular in the late 18th century many composers wrote music for the piano. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart started to learn on harpsichords when he was very small, but the piano was becoming popular when he was a young man and he wrote many sonatas and concertos for the piano. Franz Joseph Haydn also wrote a lot of piano music. Ludwig van Beethoven was a very famous pianist before he became very famous as a composer. His piano compositions include 5 concertos and 32 sonatas. In the Romantic period many composers wrote for the piano. They include Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Franz Liszt and Frederic Chopin. Later composers include Sergei Rachmaninoff, Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich and Bela Bartok.

Famous piano players

changeSome famous piano players from the early days of the piano include Dussek, Mozart, Muzio Clementi, John Field and Chopin. In the 19th century Franz Liszt was a very great influence on the piano by composing and performing very difficult music. Other great pianists include Clara Schumann and Anton Rubinstein. 20th century pianists include Artur Schnabel, Vladimir Horowitz, Josef Hofmann, Wilhelm Kempff, Dinu Lipati, Claudio Arrau, Artur Rubinstein, Sviatoslav Richter and Alfred Brendel. Among the greatest pianists today are Vladimir Ashkenazy, Daniel Barenboim, Leif Ove Andsnes, Boris Berezovsky and Evgeny Kissin.

Pianists who play popular music include Liberace, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Elton John, Billy Joel, Thelonious Monk, Tori Amos and Ray Charles. Perhaps the greatest jazz pianist was Fats Waller.

Also a number of modern harpsichordists and pianists have achieved success in fortepiano performance, including Paul Badura-Skoda, Malcolm Bilson, Andras Schiff, Kristian Bezuidenhout, Ronald Brautigam, Alexei Lubimov, duet Katie and Marielle Labeque, Yuan Sheng, Gary Cooper, Jörg Demus, Richard Egarr, Richard Fuller, Robert Hill, Geoffrey Lancaster, Vladimir Feltsman, Robert Levin, Steven Lubin, Bart van Oort, Trevor Pinnock, Viviana Sofronitsky, Andreas Staier, Melvyn Tan, Jos van Immerseel and Olga Pashchenko.

Playing the piano

changeThe piano has been a very popular instrument ever since the mid 18th century when it soon replaced the clavichord and the harpsichord. By the early 19th century the sound that the piano made was big enough to fill large concert halls. Smaller pianos were made for use in people’s homes. At first these included square pianos and giraffe pianos, later on the upright pianos became popular for home use. Pianos are not often used in orchestras (if they are, they are part of the percussion section). They may, however, be used for piano concertos (pieces for solo pianist accompanied by orchestra). There is a vast amount of music written for piano solo. The piano can also be used together with other instruments, in jazz groups, and for accompanying singing.

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ The New Dictionary of Music and Musicians ed Stanley Sadie; 1980. vol 4, p.458

- ↑ The New Dictionary of Music and Musicians ed Stanley Sadie; 1980. vol 14, p.691

- ↑ Huber, Alfons (2002). "Was the 'Viennese Action' Originally a Stossmechanik?". The Galpin Society Journal. 55: 169–182. doi:10.2307/4149041. ISSN 0072-0127. JSTOR 4149041.

- ↑ Latcham, Michael (2001). "Walter, (Gabriel) Anton". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.29863. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ↑ "Permanent Exhibition: Haydnhaus Eisenstadt". haydnhaus.at. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ↑ Ludwig van Beethoven, Brief an Nikolaus Zmeskall, Wien, November 1802, Autograph

- ↑ Conrad Graf, Echtheitsbestätigung für den Flügel Ludwig van Beethovens, Wien, 26. Juni 1849, Autograph

- ↑ August, 1887. Litzmann, Berthold, 1906. Clara Schumann, ein Künstlerleben. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, vol 3, pp.493–94.

- ↑ Chopin's letters. By Chopin, Frédéric, 1810-1849; Voynich, E. L. (Ethel Lillian), 1864-1960; Opienski, Henryk, 1870-1942

- ↑ Alan Walker, Franz Liszt: The Weimar years, 1848-1861. Cornell University Press, 1987