Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. (born Michael King, Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968)[1] was an American pastor, activist, humanitarian, and leader in the Civil Rights Movement. He was best known for improving civil rights by using nonviolent civil disobedience, based on his Christian beliefs. Because he was both a Ph.D. and a pastor, King was sometimes called the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr. (abbreviation: the Rev. Dr. King), or just Dr King.[a] He is also known by his initials MLK. He was the pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia.

Martin Luther King Jr. | |

|---|---|

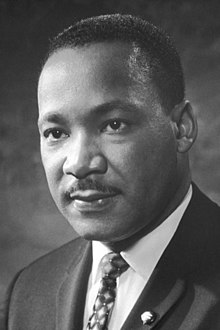

King in 1964 | |

| 1st President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference | |

| In office January 10, 1957 – April 4, 1968 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Ralph Abernathy |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Michael King Jr. January 15, 1929 Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | April 4, 1968 (aged 39) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Resting place | Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Relatives |

|

| Education | |

| Occupation |

|

| Monuments | Full list |

| Movement | |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

Martin Luther King Jr. worked hard to make people understand that not only black people but that all races should always be treated equally to white people. He gave speeches to encourage African Americans to protest without using violence.

Led by Dr. King and others, many African Americans used nonviolent, peaceful strategies to fight for their civil rights. These strategies included sit-ins, boycotts, and protest marches. Often, they were attacked by white police officers or people who did not want African Americans to have more rights. However, no matter how badly they were attacked, Dr. King and his followers never fought back.

King also helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. The next year, he won the Nobel Peace Prize.

King fought for equal rights from the start of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955 until he was murdered by James Earl Ray in April 1968.

Early life

changeMichael King, Jr. was born at 501 Auburn Avenue in Atlanta, Georgia, on January 15, 1929. [2]Although the name "Michael" appeared on his birth certificate, his name was later changed to Martin Luther in honor of German reformer Martin Luther.[3]

As King was growing up, everything in Georgia was segregated, 70 years after the Confederacy was defeated and blacks were later separated away from white people. This meant that black and white people were not allowed to go to the same schools, use the same public bathrooms, eat at the same restaurants, drink at the same water fountains, or even go to the same hospitals. Everything was separated. However, the white hospitals, schools, and other places were usually much better than the places where black people were allowed to go.[4]

At age 6, King first went through discrimination (being treated worse than a white person because he was black). He was sent to an all-black school, and a white friend was sent to an all-white school.[1]

Once, when he was 14, King won a contest with a speech about civil rights. When he was going back home on a bus, he was forced to give up his seat and stand for the bus ride so a white person could sit down.[1] At the time, white people were seen as more important than black people. If a white person wanted a seat, that person could take the seat from any African American.[4] King later said having to give up his seat made him "the angriest I've ever been in my life."[5]

Education

changeKing went to segregated schools in Georgia, and finished high school at age 15.[3] He went on to Morehouse College in Georgia, where his father and grandfather had gone.[3] After graduating from college in 1948, King decided he was not exactly the type of person to join the Baptist Church. He was not sure what kind of career he wanted. He thought about being a doctor or a lawyer. He decided not to do either, and joined the Baptist Church.[6]

King went to a seminary in Pennsylvania to become a pastor. While studying there, King learned about the non-violent methods used by Mahatma Gandhi against the British Empire in India. King was convinced that these non-violent methods would help the civil rights movement.[7]

Finally, in 1955, King earned a Ph.D. from Boston University's School of Theology.[1]

Civil rights work

changeMontgomery Bus Boycott

changeKing first started his civil rights activism in 1955. At that time, he led a protest against the way black people were segregated on buses.[8] They had to sit at the back of the bus, separate from white people.[4] He told his supporters, and the people who were against equal rights, that people should only use peaceful ways to solve the problem.[9]

King was chosen as president of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), which was created during the boycott. Rosa Parks later said: "Dr. King was chosen in part because he was relatively new to the community and so [he] did not have any enemies."[10] King ended up becoming an important leader of the boycott, becoming famous around the country, and making many enemies.[11]

King was arrested for starting a boycott. He was fined $500, plus $500 more in court costs.[12] His house was fire-bombed. Others involved with MIA were also threatened.[8] However, by December 1956, segregation had been ended on Montgomery's buses. People could sit anywhere they wanted on the buses.[13]

After the bus boycott, King and Ralph Abernathy started the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).[8] The group decided that they would only use non-violence. Its motto was "Not one hair of one head of one person should be harmed."[14] The SCLC chose King as its president.[8]

March on Washington

changeIn 1963, King helped plan the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This was the largest protest for human rights in United States history.[15] On August 28, 1963, about 250,000 people marched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial.[15][16] Then they listened to civil rights leaders speak. King was the last speaker. His speech, called "I Have a Dream," became one of history's most famous civil rights speeches.[17] King talked about his dream that one day, white and black people would be equal.

That same year, the United States government passed the Civil Rights Act. This law made many kinds of discrimination against black people illegal.[18] The March on Washington made it clear to the United States government that they needed to take action on civil rights, and it helped get the Civil Rights Act passed.[19]

Nobel Prize

changeIn 1964, King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[3] When presenting him with the award, the Chairman of the Nobel Committee said:

Today, now that mankind [has] the atom bomb, the time has come to lay our weapons and armaments aside and listen to the message Martin Luther King has given us[:] "The choice is either nonviolence or nonexistence"....

[King] is the first person in the Western world to have shown us that a struggle can be waged without violence. He is the first to make the message of brotherly love a reality in the course of his struggle, and he has brought this message to all men, to all nations and races. [7]

Voting Rights

changeKing and many others then started working on the problem of racism in voting. At the time, many of the Southern states had laws which made it very hard or impossible for African-Americans to vote. For example, they would make African Americans pay extra taxes, pass reading tests, or pass tests about the Constitution. White people did not have to do these things.[20]

In 1963 and 1964, civil rights groups in Selma, Alabama had been trying to sign African-American people up to vote, but they had not been able to. At the time, 99% of the people signed up to vote in Selma were white.[21] However, the government workers who signed up voters were all white. They refused to sign up African-Americans.[20] In January 1965, these civil rights groups asked King and the SCLC to help them. Together, they started working on voting rights.[1] However, the next month, an African-American man named Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot by a police officer during a peaceful march. Jackson died.[22]pp. 121–123 Many African-American people were very angry.

The SCLC decided to organize a march from Selma to Montgomery.[23] By walking 54 miles (87 kilometers) to the state capital, activists hoped to show how badly African-Americans wanted to vote. They also wanted to show that they would not let racism or violence stop them from getting equal rights.[21]

The first march was on March 7, 1965. Police officers, and people they had chosen to help them, attacked the marchers with clubs and tear gas. They threatened to throw the marchers off the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Seventeen marchers had to go to the hospital, and 50 others were also injured.[24] This day came to be called Bloody Sunday. Pictures and film of the marchers being beaten were shown around the world, in newspapers and on television.[25] Seeing these things made more people support the civil rights activists. People came from all over the United States to march with the activists. One of them, James Reeb, was attacked by white people for supporting civil rights. He died on March 11, 1965.[26]

Finally, President Lyndon B. Johnson decided to send soldiers from the United States Army and the Alabama National Guard to protect the marchers.[22] From March 21 to March 25, the marchers walked along the "Jefferson Davis Highway" from Selma to Montgomery.[22] Led by King and other leaders, 25,000 people who entered Montgomery on March 25.[22] He gave a speech called "How Long? Not Long" at the Alabama State Capitol. He told the marchers that it would not be long before they had equal rights, "because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."[27]

On August 6, 1965, the United States passed the Voting Rights Act. This law made it illegal to stop somebody from voting because of their race.[28]

Later work

changeAfter this, King continued to fight poverty and the Vietnam War.[1]

Death

changeKing had made enemies by working for civil rights and becoming such a powerful leader. The Ku Klux Klan did what they could to hurt King's reputation, especially in the South. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) watched King closely. They wiretapped his phones, his home, and the phones and homes of his friends.[29]

On April 4, 1968, King was in Memphis, Tennessee. He planned to lead a protest march to support garbage workers who were on strike. At 6:01 pm, he was shot while he was standing on the balcony of his motel room.[30]pp. 284–285 The bullet entered through his right cheek and travelled down his neck. It cut open the biggest veins and arteries in King's neck before stopping in his shoulder.[31]

King was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital. His heart had stopped. Doctors there cut open his chest and tried to make his heart start pumping again.[31] However, they were unable to save King's life as he died at 7:06 p.m.[30]pp. 284–285

King's death led to riots in many cities.[32]

In March 1969, James Earl Ray was found guilty of killing King. He was sentenced to 99 years in prison.[33] Ray died in 1998.[34]

Legacy

changeJust days after King's death, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968.[35] Title VIII of the Act, usually called the Fair Housing Act, made it illegal to discriminate in housing because of a person's race, religion, or home country. (For example, this made it illegal for a realtor to refuse to let a black family buy a house in a white neighborhood.) This law was seen as a tribute to King's last few years of work fighting housing discrimination in the United States.[35]

| “ | [After I die,] I'd like somebody to mention that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to give his life serving others.

... I want you to be able to say that day that I did try to feed the hungry... to clothe those who were naked... to visit those who were in prison. And I want you to say that I tried to love and serve humanity. [36] |

” |

After his death, King was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[37] King and his wife were also awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.[38]

In 1986, the United States government created a national holiday in King's honor. It is called Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. It is celebrated on the third Monday in January.[1] This is around the time of King's birthday. Many people fought for the holiday to be created, including singer Stevie Wonder.

In 2003, the United States Congress passed a law allowing the beginning words of King's "I Have a Dream" speech to be carved into the Lincoln Memorial.[39]

King County in the state of Washington, is named after King.[40] Originally, the county was named after William R. King, an American politician who owned slaves.[40] In 2005, the King County government decided the county would now be named after Martin Luther King, Jr. Two years later, they changed their official logo to include a picture of King.[40]

More than 900 streets in the United States have also been named after King. These streets exist in 40 different states; Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico. and many others[41]

In 2011, a memorial statue of King was put up on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

There are also memorials for King around the world. These include:[42]

- The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. Church in Hungary

- The King-Luthuli Transformation Center in Johannesburg, South Africa

- The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Forest in Israel's Southern Galilee area (along with the Coretta Scott King Forest in Biriya Forest, Israel)

- The Martin Luther King, Jr. School in Accra, Ghana

- The Gandhi-King Plaza (garden), at the India International Center in New Delhi, India

- A statue of King at Westminster Abbey in London

- A statue dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr. in Uppsala, Sweden.

Photo gallery

change-

Rosa Parks with King during the bus boycott (1955)

-

View of the protestors at the March on Washington (1963)

-

Lyndon Johnson and Robert Kennedy meet with King & other civil rights leaders (1963)

-

Police and protesters on the Edmund Pettus Bridge (1965)

-

President Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965 with King behind him

-

King speaks at an anti-Vietnam War rally at the University of Minnesota, St. Paul (1967)

Related pages

changeNotes

change- ↑ In the United States, a person who has any kind of Ph.D. is called a "doctor." This is not the same as being a medical doctor.

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Kirk, John A. (2016). "Did Martin Luther King Achieve His Life's Dream?". BBC Online. British Broadcasting Company, Inc. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Martin Luther King, Jr., National Historic Site--Atlanta: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2021-04-05.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Martin Luther King, Jr. – Biography". The Official Web Site of the Nobel Prize. The Nobel Foundation. 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Novkov, Julie (July 23, 2007). "Segregation (Jim Crow)". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University, The University of Alabama, and Alabama State Department of Education. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Fleming, Alice (2008). Martin Luther King Jr.: A Dream of Hope. Sterling. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4027-4439-6.

- ↑ King Jr., Martin Luther; Carson, Clayborne; Holloran, Peter; Luker, Ralph; Russell, Penny A. (1992). The papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-520-07950-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gunnar Jahn (December 10, 1964). The Nobel Peace Prize 1964 – Presentation Speech (Speech). Oslo, Norway. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Our History". Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Martin Luther King, Jr. (December 5, 1955). Address to the First Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) Mass Meeting (Speech). Montgomery, Alabama. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Parks, Rosa (2002). "Introduction". In Clayborne Carson; Kris Shepard (eds.). A Call to Conscience: The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Grand Central Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 978-0446678094.

- ↑ Fletcher, Michael A. (August 31, 2013). "Ralph Abernathy's widow says march anniversary overlooks her husband's role". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ "BBC On this Day: 1956: King convicted for bus boycott". BBC Online. British Broadcasting Corporation, Inc. 22 March 1956. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Wright, H. R. The Birth of the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1991). Charro Book Co., Inc. p.123. ISBN 0-9629468-0-X

- ↑ Sagert, Kelly Boyer (2007). The 1970s. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 24. ISBN 978-0313339196.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Official Program for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom". Bayard Rustin Papers: John F. Kennedy Library. National Archives and Records Administration. August 28, 1963. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Hansen, D, D. (2003). The Dream: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York, NY: Harper Collins. p. 177. ASIN B008TFYU54

- ↑ Moore, Lucinda (August 2003). "Dream Assignment". Smithsonian Magazine Online. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Transcript of Civil Rights Act (1964)". Avalon Project, Yale Law School. United States Congress. July 2, 1964. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Bartlett, Bruce (August 9, 2013). "The 1963 March on Washington Changed Politics Forever". The Fiscal Times. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Pildes RH 2000 (2000). "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon". Constitutional Commentary. 17. doi:10.2139/ssrn.224731. hdl:11299/168068. ISSN 1556-5068. SSRN 224731. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ 21.0 21.1 Shahn, Ben (March 19, 1965). "The Central Points". TIME Online. TIME, Inc. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Davis, Townsend (1998). Weary Feet, Rested Souls. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393318197.

- ↑ Kryn, Randall (1989). "James L. Bevel: The Strategist of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement". In David J. Garrow (ed.). We Shall Overcome: The Civil Rights Movement in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s. Carlson Publishers. ISBN 978-0926019027.

- ↑ Reed, Roy (March 6, 1966). "'Bloody Sunday' Was Year Ago". The New York Times. New York, New York. p. 76. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ↑ Sheila Jackson Hardy; Stephen Hardy (August 11, 2008). Extraordinary People of the Civil Rights Movement. Paw Prints. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-4395-2357-5.

- ↑ "Reeb, James (1927-1965)". King Institute Encyclopedia. Stanford University. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ↑ Leeman, Richard W. (1996). African-American Orators: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing. p. 220. ISBN 0-313-29014-8.

- ↑ "History of Federal Voting Rights Laws: The Voting Rights Act of 1965". Civil Rights Division. United States Department of Justice. August 8, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Christensen, Jen (December 29, 2008). "FBI tracked King's every move - CNN.com". CNN Online. Cable News Network, Turner Broadcasting, Inc. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives (1979). Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representaatives: Findings in the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr (Report). United States Government Printing Office.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 J.T. Francisco, M.D. (April 11, 1968). Autopsy Report: Martin Luther King, Jr (PDF) (Report). Tennessee Department of Public Health, Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. pp. 1–2. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Risen, Clay (2009). A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-17710-5.

- ↑ "1969: Martin Luther King's killer gets life". On This Day 1950–2005: 10 March. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Gelder, Lawrence (April 24, 1998). "James Earl Ray, 70, Killer of Dr. King, Dies in Nashville". New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "The History of Fair Housing". United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Martin Luther King, Jr. (February 4, 1968). The Drum Major Instinct (Speech). Atlanta, Georgia. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Carter, Jimmy (July 11, 1977). "Presidential Medal of Freedom Remarks on Presenting the Medal to Dr. Jonas E. Salk and to Martin Luther King, Jr". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Congressional Gold Medal Recipients (1776 to Present)". Office of the Clerk: U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Ramanathan, Lavanya (January 26, 2012). "Lincoln Memorial: The 'I Have a Dream' Etching". Washington Post Online. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 "Martin Luther King Logo: New logo is an image of civil rights leader". King County, Washington. May 24, 2011. Archived from the original on September 25, 2008. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ↑ "UT Professor Studies How Streets Are Named for Martin Luther King Jr". Office of Communications and Marketing. University of Tennessee at Knoxville. January 18, 2013. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Wax, Emily (August 23, 2011). "Martin Luther King Jr. sites across the globe". The Washington Post. Lifestyle: Full Coverage: The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

Other websites

change- Timeline of Dr. King's life Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine from BBC

- Martin Luther King at Find a Grave