History of the Earth

The history of the Earth describes the most important events and stages in the development of the planet Earth from its formation to the present day.

The age of the Earth is about 4.56 billion years.[3] Nearly all branches of science have helped us understand the main events of the Earth's past. There has been constant geological change and biological evolution. The geological time scale (GTS), as defined by international convention, shows the large span of time from the beginning of the Earth to the present.

The Earth is about one-third the age of the universe. Earth formed as part of the birth of the Solar System.[4] What eventually became the solar system started as a large, rotating cloud of dust and gas. The Sun was composed of hydrogen and some helium. All the heavier elements were produced by stars long gone. They were picked up by the Sun on its travels in the Milky Way galaxy.

The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates at least from 3.5 billion years ago during the Eoarchean era. There are microbial mat fossils, such as stromatolites, found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone discovered in Western Australia.

Other work may push this estimate back even further. The origin of life on Earth was at least 3.77 billion years ago, possibly as early as 4.41 billion years ago.[5]

Hadean

changeOrigin

changeThe formation of Earth occurred as part of the formation of the Solar System. It started as a large rotating cloud of dust and gas. This cloud, the solar nebula, was composed of hydrogen and helium produced in the Big Bang, as well as heavier elements produced in supernovas. Then, about 4.68 billion years ago, the solar nebula began to contract, rotate and gain angular momentum. This may have been triggered by a star in the region exploding as a supernova, and sending a shock wave through the solar nebula.

As the cloud rotated, it became a flat disc perpendicular to its axis of rotation. Most of the mass concentrated in the middle and began to heat up. Meanwhile, the rest of the disc began to break up into rings, with gravity causing matter to condense around dust particles. Small fragments collided to become larger fragments, including one collection about 150 million kilometres (93 million miles) from the center: this would become the Earth. As the Sun condensed and heated, nuclear fusion started, and the solar wind cleared out most of the material in the disc which had not yet condensed into larger bodies. The same process is expected to produce accretion disks around virtually all newly forming stars in the universe, some of which yield planets.

Moon

changeThe Earth's relatively large natural satellite is the Moon. [6] During the Apollo program, rocks from the Moon's surface were brought to Earth. Radiometric dating of these rocks has shown the Moon to be 4527 ± 10 million years old, about 30 to 55 million years younger than other bodies in the solar system.[7][8] New evidence suggests the Moon formed even later, 4.48±0.02 Ga (billion years ago), or 70–110 mya after the start of the Solar System.[9] Another notable feature is the relatively low density of the Moon, which must mean it does not have a large metallic core, like all other terrestrial bodies in the solar system.

Theories for the formation of the Moon must explain its late formation as well as the following facts. First, the Moon has a low density (3.3 times that of water, compared to 5.5 for the Earth) and a small metallic core. Second, there is virtually no water or other volatiles on the Moon. Third, the Earth and Moon have the same oxygen isotopic signature (relative abundance of the oxygen isotopes). The Moon has a bulk composition closely resembling the Earth's mantle and crust together, without the Earth's core. This has led to the giant impact hypothesis: the idea that the Moon was formed by a giant impact of the proto-Earth with another protoplanet.[10]

The impactor, sometimes named Theia, is thought to have been a little smaller than the current planet Mars. Theia finally collided with Earth about 4.533 Ga.[11] Models reveal that when an impactor this size struck the proto-Earth at a low angle and relatively low speed (8–20 km/s or 5.0–12.4 mi/s), much material from the mantles (and proto-crusts) of the proto-Earth and the impactor was ejected into space, where much of it stayed in orbit around the Earth. This material would eventually form the Moon. However, the metallic cores of the impactor would have sunk through the Earth's mantle to fuse with the Earth's core, depleting the Moon of metallic material.[12] The giant impact hypothesis thus explains the Moon's abnormal composition.[13] The ejecta in orbit around the Earth could have condensed into a single body within a couple of weeks. Under the influence of its own gravity, the ejected material became a more spherical body: the Moon.

The radiometric ages show the Earth existed already for at least 10 million years before the impact, enough time to allow for differentiation of the Earth's primitive mantle and core. Then, when the impact occurred, only material from the mantle was ejected, leaving the Earth's core of heavy elements untouched.

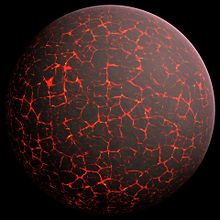

The impact had some important consequences for the young Earth. It released an enormous amount of energy, causing both the Earth and Moon to be completely molten. Immediately after the impact, the Earth's mantle was vigorously convecting, the surface was a large magma ocean. The planet's first atmosphere must have been completely blown away by the enormous amount of energy released.[14] The impact is also thought to have changed Earth’s axis to produce the large 23.5° axial tilt that is responsible for Earth’s seasons (a simple, ideal model of the planets’ origins would have axial tilts of 0° with no recognizable seasons). It may also have sped up Earth’s rotation.

Archean

changeArchean Earth

changeAt the beginning of the Archean, the Earth's heat flow was nearly three times higher than it is today, and was still twice the current level by the beginning of the Proterozoic. Thus, plates and volcanic activity were considerably more active than they are today; the Earth's crust was not only thinner than is today, but probably broken up into many more tectonic plates, with numerous hot spots, rift valleys, and transform faults. The existence of plate tectonics in this eon is disputed: it is an active area of modern research.[15]p297-302

There were no large continents until late in the Archean; small protocontinents were the norm, prevented from coalescing into larger units by the high rate of geologic activity. These felsic protocontinents probably formed at hot spots rather than subduction zones, from a variety of sources: mafic magma melting more felsic rocks, partial melting of mafic rock, and from the metamorphic alteration of felsic sedimentary rocks.[15]p297-301

The Archean atmosphere apparently lacked free oxygen. Temperatures appear to have been near modern levels, although astronomers think that the sun was about one-third dimmer. This suggests larger amounts of greenhouse gases than later in Earth history.

Archean geology

changeWhen the Archean began, the Earth's heat flow was nearly three times as high as it is today, and it was still twice the current level at the transition from the Archean to the Proterozoic (2,500 Ma). The extra heat was the result of a mix of remnant heat from planetary accretion, from the formation of the metallic core, and from the decay of radioactive elements.

The oldest rock formations exposed on the surface of the Earth are Archean or slightly older. Archean rocks are known from Greenland, the Canadian Shield, western Australia, and southern Africa. Although the first continents formed during this eon, rock this age makes up only 7% of the world's current cratons; even allowing for erosion and destruction of past formations, evidence suggests that only 5-40% of the present continental crust formed during the Archean.[15]p301

In contrast to the Proterozoic, Archean rocks are often heavily metamorphized deep-water sediments, such as greywackes, mudstones, volcanic sediments, and banded iron formations. Greenstone belts are typical Archean formations: they are made of alternating high and low-grade metamorphic rocks. The high-grade rocks come from volcanic island arcs, and the low-grade metamorphic rocks come from deep-sea sediments. These sediments eroded from the island arcs and ended in a forearc basin. In short, greenstone belts show where protocontinents were stuck together.[15]p302-3

Archean life

changeThe processes that gave rise to life on Earth are not completely understood, but there is substantial evidence that life came into existence either near the end of the Hadean Eon or early in the Archean Eon.

The earliest evidence for life on Earth is graphite of biogenic origin found in 3.7 billion–year-old metasedimentary rocks discovered in Western Greenland. Fossils of cyanobacterial mats (stromatolites) are found throughout the Archean—becoming especially common late in the eon—while a few other probable bacterial fossils are known from chert beds.[15]p307 In addition to bacteria, microfossils of the extremophilic archaea have also been identified.

Life in the Archean was limited to simple single-celled organisms (lacking nuclei), called prokaryotes. In addition to the domain Bacteria, microfossils of the domain Archaea have also been identified. There are no known eukaryote fossils.[15]p306, 323 No fossil evidence yet exists for viruses. Fossilized microbes from terrestrial microbial mats show that life was already established on land 3.22 billion years ago.

Proterozoic

changeThe Proterozoic record

changeThe geologic record of the Proterozoic is much better than that for the preceding Archaean. In contrast to the deep-water deposits of the Archean, the Proterozoic features many strata that were laid down in extensive, shallow epicontinental seas; furthermore, many of these rocks are less metamorphosed than Archean-age ones, and plenty are in fact unaltered.[15]p315 Study of these rocks show that the eon featured rapid continental accretion (unique to the Proterozoic), supercontinent cycles, and mountain-building (orogeny) activity.[15]p315/8; 329/32

The first known glaciations occurred during the Proterozoic. One ice age began shortly after the beginning of the eon. There were at least four during the Neoproterozoic, climaxing with the "Snowball Earth" of the Varangian glaciation.[15]p320; 325

The build-up of oxygen

changeThe Great Oxygenation Event was one of the most important events of the Proterozoic. Though oxygen was undoubtedly released by photosynthesis well back in Archean times, it could not build up to any significant degree until chemical sinks--unoxidized sulfur and iron—had been filled; until roughly 2.3 billion years ago, oxygen was probably only 1 to 2% of its current level.(Stanley, 323) Banded iron formations, which provide most of the world's iron ore, were also a prominent chemical sink; most accumulation ceased after 1.9 billion years ago, either due to an increase in oxygen or a more thorough mixing of the oceanic water column.[15]p324

Red beds, which are coloured by haematite, indicate an increase in atmospheric oxygen after 2 billion years ago; they are not found in older rocks.(Stanley, 324) The oxygen build-up was probably due to two factors: a filling of the chemical sinks, and an increase in carbon burial, which stored organic compounds which would have otherwise been oxidized by the atmosphere.[15]p325

Proterozoic life

changeThe first advanced single-celled and multi-cellular life roughly coincides with the oxygen accumulation; this may have been due to an increase in the oxidized nitrates that eukaryotes use, as opposed to cyanobacteria.(Stanley, 325) It was also during the Proterozoic that the first symbiotic relationship between mitochondria (for animals and protists) and chloroplasts (for plants) and their hosts evolved.[15]p321-2

Eukaryotes such as acritarchs blossomed, as did cyanobacteria; in fact, stromatolites reached their greatest abundance and diversity during the Proterozoic, peaking roughly 1.2 billion years ago.[15]321-3

Classically, the boundary between the Proterozoic and the Paleozoic was set at the base of the Cambrian period when the first fossils of animals known as trilobites appeared. In the second half of the 20th century, a number of fossil forms have been found in Proterozoic rocks, but the boundary of the Proterozoic is still fixed at the base of the Cambrian: that is 542 mya.

Phanerozoic

changePaleozoic

changeThe Paleozoic covers the time from the first appearance of abundant, hard-shelled fossils to the time when the continents were beginning to be dominated by large, relatively sophisticated reptiles and relatively modern plants. The Paleozoic is a time in Earth's history when complex life forms evolved, took their first breath of oxygen on dry land, and when the forerunners of all multicelular life on Earth began to diversify. There are six periods in the Paleozoic era: Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian.

The upper (youngest) boundary is set at a major extinction event 250 million years later, known as the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Modern practice sets the older boundary at the first appearance of a distinctive trace fossil called Phycodes pedum.

Geologically, the Paleozoic starts shortly after the breakup of a supercontinent called Rodinia and at the end of a global ice age (Snowball Earth). Throughout the early Palaeozoic, the Earth's landmass was broken up into a substantial number of relatively small continents. Toward the end of the era, the continents gathered together into a supercontinent called Pangaea, which included most of the Earth's land area.

At the start of the era, life was confined to bacteria, algae, sponges and a variety of somewhat enigmatic forms known collectively as the Ediacaran fauna. A large number of body plans appeared nearly simultaneously at the start of the era—a phenomenon known as the Cambrian Explosion.

There is some evidence that simple life may already have invaded the land at the start of the Palaeozoic, but substantial plants and animals did not take to the land until the Silurian and did not thrive until the Devonian. Although primitive vertebrates are known near the start of the Palaeozoic, animal forms were dominated by invertebrates until the mid-Palaeozoic. Fish populations exploded in the Devonian. During the late Palaeozoic, great forests of primitive plants thrived on land forming the great coal beds of Europe and eastern North America. By the end of the era, the first large, sophisticated reptiles and the first modern plants (conifers) had developed.

Mesozoic

changeThe Mesozoic covers the time when life was dominated by large sophisticated reptiles. The lower (oldest) boundary is set by the P/Tr extinction event. The upper (youngest) boundary is set at the K/T extinction event.

Geologically, the Mesozoic starts with almost all the Earth's land collected into a supercontinent called Pangaea. During the era, Pangaea split into the northern continent Laurasia and the southern continent Gondwana. Laurasia then split into North America and Eurasia. Gondwana broke up progressively into continents: South America, Africa, Madagascar, India, Australia and Antarctica.

The Mesozoic is known as the Age of Dinosaurs. It also saw the development of early birds and mammals and, later, flowering plants (angiosperms). At the end of the Mesozoic, all the major body plans of modern life were in place, though in some cases – notably the mammals – the forms that existed at the end of the Cretaceous were relatively primitive.

Cenozoic

changeThe Cenozoic is the age of mammals. During the Cenozoic, mammals diverged from a few small, simple, generalized forms into a diverse collection of terrestrial, marine, and flying animals. Flowering plants and birds also evolved substantially in the Cenozoic .

Geologically, the Cenozoic is the era when continents moved into their current positions. Africa and Australasia split from Gondwana to drift north, and India collided with Southeast Asia; Antarctica moved into its current position over the South Pole; the Atlantic Ocean widened and, late in the era, South America became attached to North America.

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ Bowring, Samuel A.; Williams, Ian S. (1999). "Priscoan (4.00-4.03 Ga) orthogneisses from northwestern Canada". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 134 (1): 3–16. Bibcode:1999CoMP..134....3B. doi:10.1007/s004100050465. S2CID 128376754.

- ↑ Discovery of world's oldest rocks challenged

- ↑ Dalrymple, G. Brent 2004. Ancient Earth, ancient skies: the age of Earth and its cosmic surroundings. Stanford.

- ↑ Manhesa, Gérard; Allègre, Claude J.; Dupréa, Bernard & Hamelin, Bruno (1980). "Lead isotope study of basic-ultrabasic layered complexes: Speculations about the age of the earth and primitive mantle characteristics". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 47 (3): 370–382. Bibcode:1980E&PSL..47..370M. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(80)90024-2.

- ↑ Staff (20 August 2018). A timescale for the origin and evolution of all of life on Earth. Phys.org. Retrieved 20 August 2018. [1]

- ↑ The Earth's Moon is larger relative to its planet than any other satellite in the Solar System. Pluto's satellite Charon is relatively larger, but Pluto is considered a dwarf planet.

- ↑ Kleine et al. 2005. Hf-W chronometry of lunar metals and the age and early differentiation of the Moon. Science 310, 1671–1674.

- ↑ Halliday A.N. 2006. The origin of the Earth; what's new? Elements 2 205-210.

- ↑ Halliday, Alex N 2008. A young Moon-forming giant impact at 70–110 million years accompanied by late-stage mixing, core formation and degassing of the Earth. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 366, 4163-4181. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0209. http://rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/366/1883/4163.full.

- ↑ Ida S. Canup R.M. & Stewart G.M. 1997. Lunar accretion from an impact-generated disk, Nature 389, 353-357.

- ↑ Münker, Carsten et al. 2003. Evolution of planetary cores and the Earth-Moon system from Nb/Ta systematics. Science 301 (5629): 84–87. doi:10.1126/science.1084662. PMID 12843390. http://sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/301/5629/84 Archived 2005-09-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Liu L-G. 1992. Chemical composition of the Earth after the giant impact. Earth, Moon, and Planets 57, 85-97.

- ↑ Newsom H.E. & Taylor S.R. 1989. Geochemical implications of the formation of the Moon by a single giant impact. Nature 338, 29-34.

- ↑ Benz W. & Cameron A.G.W. 1990. Terrestrial effects of the giant impact. LPI Conference on the Origin of the Earth, 61-67.

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 15.12 Stanley S.M. 2008. Earth system history. Freeman, San Francisco.

Other websites

changeOther sources

change- New Scientist Essential Guide #17: Planet Earth: the incredible story of our unique home. Published in 2023, and full of interesting ideas.