Esperanto

Esperanto is a constructed auxiliary language. Its creator was L. L. Zamenhof, a Polish eye doctor. He created the language to make international communication easier. His goal was to design Esperanto in such a way that people can learn it much more easily than any other national language.

| Esperanto | |

|---|---|

| International language | |

| Esperanto | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [espeˈranto] ( |

| Created by | L. L. Zamenhof |

| Date | 1887 |

| Setting and usage | International auxiliary language |

| Users | Native: estimated 1000 to several thousand (2016)[1][2] L2 users: estimates range from 63 000[3] to two million[4] |

| Purpose | constructed language

|

Early form | |

| Latin script (Esperanto alphabet) Esperanto Braille | |

| Signuno | |

| Sources | Vocabulary from Romance and Germanic languages, grammar from Slavic languages |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | Akademio de Esperanto |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | eo |

| ISO 639-2 | epo |

| ISO 639-3 | epo |

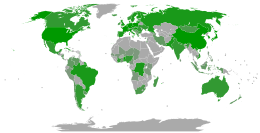

Esperantujo: 120 countries worldwide | |

At first, Zamenhof called the language La Internacia Lingvo, which means "The International Language" in Esperanto. Soon, people began calling it by the simpler name Esperanto, which means "one who hopes". That name comes from Doktoro Esperanto ("A doctor who hopes"), which is what Zamenhof called himself in his first book about Esperanto.

There are people who speak Esperanto in many countries and in all the major continents. No one knows exactly how many people now speak Esperanto in the world. Most sources say that there are between several hundred thousand and two million Esperanto speakers.[6] A few people grew up speaking Esperanto as their first language. There may perhaps be around 2,000 of these people.[7] Therefore, Esperanto is the most-used constructed language in the world.

A person who speaks or supports Esperanto is often called an "Esperantist".

History

changeZamenhof's childhood

changeL. L. Zamenhof created Esperanto. He grew up in Białystok, a town that was in the Russian Empire, but is now in Poland. People in Białystok spoke many languages. Zamenhof saw conflicts between individual ethnic groups living there (Russians, Poles, Germans and Jews).[8] He thought that lack of a common language caused these conflicts, so he began creating a language people could share and use internationally.[9] He thought this language should be different from national languages. He wanted it to be culturally neutral and easy-to-learn. He thought people should learn it along with national languages and use Esperanto for communication between people with different native languages.

First attempts

changeFirst, Zamenhof thought about bringing Latin back into use. Although he learned it in school, he realized it was too difficult for normal use. He also studied English and understood that languages did not need to conjugate verbs by person or number. Once he saw two Russian words: швейцарская (reception, derived from швейцар - receptionist) and кондитерская (confectionery, derived from кондитер - confectioner). These words with the same ending gave him an idea. He decided that regular prefixes and suffixes could decrease the number of word roots, which one would need for a communication. Zamenhof wanted the root words to be neutral, so he decided to use word roots from Romance and Germanic languages. Those languages were taught in many schools in many places around the world at that time.

Creation of the final version

changeZamenhof did his first project Lingwe uniwersala (Universal Language) in 1878. But his father, a language teacher, regarded his son's work as unrealistic. So, he destroyed the original work. Between 1879 and 1885 Zamenhof studied medicine in Moscow and Warsaw. In these days he again worked on an international language. In 1887 he published his first textbook Международный языкъ ("The International Language"). According to Zamenhof's pen-name Doktoro Esperanto ("Doctor who hopes"), many people started calling the language as Esperanto.[10]

First attempts to change

changeZamenhof received a lot of enthusiastic letters. In the letters, people wrote their suggestions for changes to the language. He noted all of the suggestions. He published them in the magazine La Esperantisto. In this magazine, Esperanto speakers could vote about the changes. They did not accept them. The magazine had many subscribers in Russia. It was eventually banned (stopped) there because of an article about Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy. Publishing of the magazine ended after that. The new magazine Lingvo Internacia replaced it.[11][12]

Progress of the community

changeIn the first years of Esperanto's life, people used it only in written form, but in 1905 they organized the first (1st) World Congress of Esperanto in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. This was the first notable use of Esperanto in international communication. Because of the success of the congress, it is organized each year (except years of the World Wars) to this day.

In 1912 Zamenhof resigned his leading position in the movement during the eighth (8th) World Congress of Esperanto in Kraków, Poland. The tenth (10th) World Congress of Esperanto in Paris, France, did not take place because of the start of World War I. Nearly 4000 people signed up for this congress.[13]

Times of the World Wars

changeDuring World War I the World Esperanto Association had its main office in Switzerland, which was neutral in the war. Hector Hodler's group of volunteers with support of Romain Rolland helped send letters between the enemy countries through Switzerland. In total, they helped with 200,000 cases.[13]

After World War I there was new hope for Esperanto because of the desire of people to live in peace. Esperanto and its community grew in those days. The first World Congress after the war took place in Hague, Netherlands, in 1920. An Esperanto Museum was opened in Vienna, Austria, in 1929. Today it is part of the Austrian National Library.

World War II stopped this growing of the language. Many Esperantists were sent into the battle. Nazis broke up Esperanto groups because they saw the language as a part of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy. Many Esperanto speakers died in concentration camps. The Soviet Union also treated Esperantists badly when Stalin was their leader.[14][15]

After the wars

changeAfter World War II many people supported Esperanto. 80 million people signed a petition supporting Esperanto for use in the United Nations.[16]

Every year they organize big Esperanto meetings such as the World Congress of Esperanto, International Youth Congress of Esperanto and SAT-Congress (meeting of Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda - World Non-national Association).

In 1990, the Holy See published the document Norme per la celebrazione della Messa in esperanto, allowing the use of Esperanto in Masses without special permission.[17][18][19] Esperanto is the only constructed language which received a permission like this one from the Roman Catholic Church.

Esperanto has many web pages, blogs, podcasts, and videos. People also use Esperanto in social media and online discussions and in their private communication through e-mail and instant messaging. Several (especially open source and free software) programmes have their own language version in Esperanto. Internet radio station Muzaiko has been broadcasting 24 hours a day in Esperanto since 2011.[20]

Goals of the Esperanto movement

changeZamenhof wanted to make an easy language to increase international understanding. He wanted Esperanto to be a universal second language. In other words, although he did not want Esperanto to replace national languages, he wanted a majority of people around the world to speak Esperanto. Many Esperantists initially shared this goal. General Assembly of UNESCO recognized Esperanto in 1954.[21] Since then World Esperanto Association has got official relations with UNESCO.[22] However, Esperanto was never chosen by the United Nations or other international organizations and it has not become a widely accepted second language.

Some Esperanto speakers like Esperanto for reasons other than its use as a universal second language. They like the Esperanto community and culture. Developing the Esperanto culture is a goal for that people.

People who care more about Esperanto's current value than about its potential for universal use are sometimes called raŭmistoj in Esperanto. The ideas of these people can together be called raŭmismo, or "Raumism" in English. The names come from the name of the town of Rauma, in Finland. The International Youth Congress of Esperanto met there in 1980 and made a big statement. They said that making Esperanto a universal second language was not their main goal.

People who have goals for Esperanto that are more similar to Zamenhof's are sometimes called finvenkistoj in Esperanto. The name comes from fina venko, an Esperanto phrase which means "final victory". It refers to a theoretical future in which nearly everyone on Earth speaks Esperanto as a second language.

The Prague Manifesto (1996) states the ideas of the ordinary people of the Esperanto movement and of its main organization, the World Esperanto Association (UEA).

German town Herzberg am Harz uses nickname die Esperanto-Stadt/la Esperanto-urbo ("the Esperanto town") since July 12, 2006. They also teach the language in elementary schools and do some other cultural and educational events using the Esperanto language together with the Polish twin town Góra.[23]

Esperanto is the only constructed language that the Roman Catholic Church recognises as a liturgical language. They allow Masses in the language and Vatican Radio broadcasts in Esperanto every week.[17][18][24]

Esperanto culture

changeMany people use Esperanto to communicate by mail, email, blogs or chat rooms with Esperantists in other countries. Some travel to other countries to meet and talk in Esperanto with other Esperantists.

Meetings

changeThere are annual meetings of Esperantists. The largest is the Universala Kongreso de Esperanto ("World Congress of Esperanto"), which is held in a different country each year. In recent years around 2,000 people have attended it, from 60 or more countries. For young people there is Internacia Junulara Kongreso ("International Youth Congress of Esperanto").

A lot of different cultural activities take place during Esperanto meetings: concerts of Esperanto musicians, dramas, discos, presentations of the culture of the host country and culture of the countries of the participants, lectures, language-courses, and so on. At the location of Esperanto meetings there is also a pub, a tearoom, a bookstore, etc. with Esperanto-speaking workers. The number of activities and possibilities depends on the size or on the theme of the meeting.

Literature

changeThere are books and magazines written in Esperanto. Much literature has been translated into Esperanto from other languages, including famous works, like the Bible (first time in 1926) and plays by Shakespeare. Works that are less famous have also been translated into Esperanto, and some of these do not have English translations.

Important Esperanto writers are for example: Trevor Steele (Australia), István Nemere (Hungary) and Mao Zifu (China). William Auld was a British writer of poetry in Esperanto and honorary president of the Esperanto PEN Centre (Esperanto part of International PEN). Some people recommended him for the Nobel Prize in Literature.[25]

Music

changeThere is music of different genres in Esperanto, including folk songs, rock music, cabaret, songs for solo singers, choirs and opera. Among active Esperanto musicians is for example Swedish socio-critical music group La Perdita Generacio, Occitan singer JoMo, the Finnish group Dolchamar, Brazilian group Supernova, Frisian group Kajto or Polish singer-songwriter Georgo Handzlik. Also some popular music writers and artists, including Elvis Costello and American singer Michael Jackson recorded songs in Esperanto, composed songs inspired by the language or used it in their promotional materials. Some songs from the album Esperanto from Warner Bros., which released - all in Esperanto - in Spain, in November 1996, reached a high position in the Spanish record charts; similarly, in 1999, in Germany, hip-hop music group Freundeskreis became famous with their single Esperanto. Classical works for orchestra and choir with texts in Esperanto are La Koro Sutro by Lou Harrison and The First Symphony by David Gaines. In Toulouse, France, there is Vinilkosmo, which produces Esperanto music. The main internet Esperanto songbook KantarViki has got 3,000 songs in May 2013, both original and translated.[26]

Theatre and movies

changeThey play dramas from different writers such as Carlo Goldoni, Eugène Ionesco and William Shakespeare also in Esperanto. Filmmakers sometimes use Esperanto in the background of films, for example in The Great Dictator by Charlie Chaplin, in the action film Blade: Trinity or in comedy sci-fi television series Red Dwarf. Feature films in Esperanto are not very common, but there are about 15 feature films, which have Esperanto themes.

The 1966 film Incubus is notable because its dialogues are in Esperanto only. Today some people translate subtitles of different films to Esperanto. The website Verda Filmejo collects these subtitles.[27]

Radio and television

changeRadio stations in Brazil, China, Cuba[28] and Vatican[24] broadcast regular programmes in Esperanto. Some other radio programmes and podcasts are available on the Internet. Internet radio station Muzaiko broadcasts Esperanto programmes on the Internet 24 hours a day since July 2011.[20] Between 2005 and 2006 there was also a project of international television "Internacia Televido" in Esperanto. Esperanto TV broadcasts on the Internet from Sydney, Australia, since April 5, 2014.[29]

Internet

changeOn the Internet there are many online discussions in Esperanto about different topics. There are many websites, blogs, podcasts, videos, television, and radio stations in Esperanto (see above). Google Translate supports translations from and into Esperanto since February 22, 2012 as its 64th language.[30]

Apart from websites and blogs of esperantists and Esperanto organizations, there is also an Esperanto Wikipedia (Vikipedio) and other projects of Wikimedia Foundation which has also got their Esperanto language version or they use Esperanto (Wikibooks, Wikisource, Wikinews, Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata). People can also use an Esperanto version of social networks, for example Facebook, Diaspora and other websites.

Several computer programmes also have an Esperanto version, such as web browser Firefox[31] and office suite (set of programmes for use in an office) LibreOffice.[32]

The language

changeEsperanto uses grammar and words from many natural languages, such as Latin, Russian, and French. Morphemes in Esperanto (the smallest parts of a word that can have a meaning) cannot be changed and people can combine them into many different words. The language has got common attributes with isolating languages (they use word order to change the meaning of a sentence) such as Chinese, while the inner structure of Esperanto words has got common attributes with agglutinative languages (they use affixes to change the meaning of a word), such as Turkish, Swahili and Japanese.

Esperanto's grammar (rules of language) is meant to be simple. The rules in Esperanto never change and can always be applied in the same way

Alphabet

changeThe Esperanto alphabet is based on the Latin script. It has six letters with diacritics: ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ (with circumflex), and ŭ (with breve). The alphabet does not have the letters q, w, x, or y.

The 28-letter alphabet is:

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital letter | A | B | C | Ĉ | D | E | F | G | Ĝ | H | Ĥ | I | J | Ĵ | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | Ŝ | T | U | Ŭ | V | Z |

| Small letter | a | b | c | ĉ | d | e | f | g | ĝ | h | ĥ | i | j | ĵ | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ŝ | t | u | ŭ | v | z |

| IPA phoneme | a | b | t͡s | t͡ʃ | d | e | f | ɡ | d͡ʒ | h | x | i | j=i̯ | ʒ | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ʃ | t | u | w=u̯ | v | z |

- A is like a in father

- B is like b in boy

- C is like zz in pizza

- Ĉ is like ch in chair

- D is like d in dog

- E is like e in egg

- F is like f in flower

- G is like g in go

- Ĝ is like j in jam

- H is like h in honey

- Ĥ is like ch in Scottish loch

- I is like i in it or ee in feed

- J is like y in yes

- Ĵ is like s in measure

- K is like k in king

- L is like l in look

- M is like m in man

- N is like n in no

- O is like o in open

- P is like p in pie

- R is like r in road but is rolled (trilled, as in Spanish, Italian, Arabic, Russian)

- S is like s in simple

- Ŝ is like sh in sheep

- T is like t in tree

- U is like u in bull or oo in food

- Ŭ is like w in well

- V is like v in cave

- Z is like s in his.

Writing diacritics

changeEven though the world uses Unicode, the letters with diacritics (found in the "Latin-Extended A" section of the Unicode Standard) can cause problems with printing and computing, because they are not found on the keyboards we use.

There are two remedies of this problem, both of which use digraphs for the letters with diacritics. Zamenhof, the inventor of Esperanto, devised an "h-system", which replaces ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, and ŭ with ch, gh, hh, jh, sh, and u, respectively. A more recent "x-system" has also been used, which replaces ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, and ŭ with cx, gx, hx, jx, sx, and ux, respectively.

There are computer keyboard layouts that support the Esperanto alphabet, for example, Amiketo for Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux, Esperanta Klavaro for Windows Phone,[33] and Gboard & AnySoftKeyboard for Android.

Examples of words

change- from Romance languages

- from Germanic languages

- from Slavic languages

- from other Indo-European languages

- from Finno-Ugric languages

- from Semitic languages

- from other languages

Criticism

changeSome of the criticism of Esperanto is common for any project of constructed international language: a new language has little chance to replace today's international languages like English, Arabic and others.

The criticism, which is specific for Esperanto, targets various parts of the language itself (the special Esperanto letters, the -n ending, sound of the language, and so on).[34]

Some people say that use of the diacritics (the letters ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, ŭ) make the language less neutral than it would be using only the basic letters of Latin alphabet.[35] No other language uses the letters ĉ, ĥ and ĵ. The letter ĥ is the least used letter in Esperanto and ĵ is not used frequently either, leading people to question how necessary they are.

Critics of Esperanto also say that the same ending of an adjective and a noun (such as "bona lingvo", "bonaj lingvoj", "bonajn lingvojn") is unnecessary.[36] English, for example, does not have the requirement that an adjective and noun must agree in tense, and has no indicator for accusative cases.

They also criticize the fact that most of the words in Esperanto come from Indo-European languages, which makes the language less neutral.

One of the common criticisms from both non-Esperanto-speakers and those who speak Esperanto, is that there is language sexism in Esperanto. Some words by default refer to males, and the feminine counterparts have to be constructed by adding the -in- suffix to the masculine root.[37][38] Such a words are words like patro (father) and patrino (mother), filo (son) and filino (daughter), onklo (uncle) and onklino (aunt), and so on. The majority of all Esperanto words have no specific meaning on the basis of sex.[39] Some people proposed the suffix -iĉ- with male meaning in order to make the meaning of the basic word neutral.[38] However this proposal is not widely accepted by Esperanto speakers.

Criticism of some parts of Esperanto motivated the creation of various new constructed languages like Ido, Novial, Interlingua and Lojban. However, none of these constructed languages have as many speakers as Esperanto does.

Example of text

changeNormal sample: Ĉiuj homoj estas denaske liberaj kaj egalaj laŭ digno kaj rajtoj. Ili posedas racion kaj konsciencon, kaj devus konduti unu la alian en spirito de frateco.

Version in h-system: Chiuj homoj estas denaske liberaj kaj egalaj lau digno kaj rajtoj. Ili posedas racion kaj konsciencon, kaj devus konduti unu la alian en spirito de frateco.

Version in x-system: Cxiuj homoj estas denaske liberaj kaj egalaj laux digno kaj rajtoj. Ili posedas racion kaj konsciencon, kaj devus konduti unu la alian en spirito de frateco.

Simple English translation: All people are free and equal in dignity and rights. They are reasonable and moral, and should act kindly to each other.

Lord's Prayer

change| Esperanto | English | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | H-system | X-system | |

| Patro nia, kiu estas en la ĉielo, | Patro nia, kiu estas en la chielo, | Patro nia, kiu estas en la cxielo, | Our Father, which art in heaven, |

| Cia nomo estu sanktigita. | Cia nomo estu sanktigita. | Cia nomo estu sanktigita. | Hallowed be thy Name. |

| Venu Cia regno, | Venu Cia regno, | Venu Cia regno, | Thy kingdom come, |

| plenumiĝu Cia volo, | plenumighu Cia volo, | plenumigxu Cia volo, | Thy will be done, |

| kiel en la ĉielo, tiel ankaŭ sur la tero. | kiel en la chielo, tiel ankau sur la tero. | kiel en la cxielo, tiel ankaux sur la tero. | in earth, as it is in heaven. |

| Nian panon ĉiutagan donu al ni hodiaŭ. | Nian panon chiutagan donu al ni hodiau. | Nian panon cxiutagan donu al ni hodiaux. | Give us this day our daily bread. |

| Kaj pardonu al ni niajn ŝuldojn, | Kaj pardonu al ni niajn shuldojn, | Kaj pardonu al ni niajn sxuldojn, | And forgive us our trespasses, |

| kiel ankaŭ ni pardonas al niaj ŝuldantoj. | kiel ankau ni pardonas al niaj shuldantoj. | kiel ankaux ni pardonas al niaj sxuldantoj. | as we forgive them that trespass against us. |

| Kaj ne konduku nin en tenton, | Kaj ne konduku nin en tenton, | Kaj ne konduku nin en tenton, | And lead us not into temptation, |

| sed liberigu nin de la malbono. | sed liberigu nin de la malbono. | sed liberigu nin de la malbono. | but deliver us from evil. |

Metaphoric use of the word "Esperanto"

changePeople sometimes use the word "Esperanto" in a metaphoric way (not in its literal sense). They use it to say that something aims to be international or neutral, or it uses a wide mixture of ideas. They say the programming language Java is "independent of specific computer systems [e.g. Windows, Android] like Esperanto is independent of ... nations".[40] Similarly, they call the font Noto "the Esperanto of fonts" because it tries to work well for every culture's writing.[41]

References

change- ↑ Harald Haarmann, Eta leksikono pri lingvoj, 2011, archive date March 4, 2016: Esperanto … estas lernata ankaŭ de pluraj miloj da homoj en la mondo kiel gepatra lingvo. ("Esperanto has also been learned by several thousand people in the world as a mother tongue.")

- ↑ Jouko Lindstedt, Jouko, Oftaj demandoj pri denaskaj Esperant‑lingvanoj ("Frequently asked questions about native Esperanto speakers"), archive date March 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Nova takso: 60.000 parolas Esperanton" [New estimate: 60.000 speak Esperanto] (in Esperanto). Libera Folio. February 13, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Esperanto" (20th ed.). Ethnologue. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ↑ What is UEA?, Universal Esperanto Association, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ↑ Simons, Gary F.; Charles D. Fennig (2017). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World". Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ↑ Keating, Fiona (December 14, 2015). "Top 10 facts you didn't know about Esperanto". International Business Times. IBTimes Co.

Up to 2 million people worldwide are estimated to speak Esperanto, including around 2,000 native speakers who learned Esperanto from birth.

- ↑ Salisbury, Josh (December 6, 2017). "'Saluton!': the surprise return of Esperanto". The Guardian. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

A Jewish-Polish doctor born in 1859 in Białystok, now in Poland, Zamenhof grew up under Russian occupation. Violence between different groups was common – Białystok which was a melting pot of Protestant Germans, Catholic Poles, Orthodox Russians and Jews.

- ↑ "ZAMENHOF, LAZARUSLUDWIG". JewishEncyclopedia.com. 2002. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Vondroušek, Josef. "Z histórie esperanta" (in Slovak). Archived from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Kolker, Boris (1998–1999). "Enigmoj de Ludoviko Zamenhof" (in Esperanto). Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Informfluoj en Esperantujo" (in Esperanto). September 9, 2005. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Milita periodo". Enciklopedio de Esperanto. Budapest: Literatura Mondo. 1933. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ Keating, Fiona (December 14, 2015). "Top 10 facts you didn't know about Esperanto". International Business Times. IBTimes Co.

- ↑ Penarredonda, Jose Luis (January 10, 2018). "The invented language that found a second life online". BBC Future. BBC. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ↑ Malovec, Miroslav. "Esperantští spisovatelé a jejich díla" (in Czech). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

První petici ve prospěch esperanta Spojeným národům podepsalo téměř 17 miliónů lidí, druhou petici, adresovanou rovněž Spojeným národům podepsalo přes 80 miliónů lidí,...

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "La dekreto pri la normoj por la celebro de la Meso en esperanto" (in Esperanto and Italian). IKUE. Archived from the original on August 19, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "La dekreto por la aprobo de la Meslibro kaj Legaĵaro en Esperanto" (in Esperanto and Latin). IKUE. Archived from the original on August 19, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Catholic Prayers in the Languages of the World: Esperanto" (in English and Esperanto). Città del Vaticano: Agenzia Fides. December 7, 2006. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Muzaiko planas sendi retradion en Esperanto senpaŭze" (in Esperanto). Libera Folio. September 14, 2011. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Rezolucio de 1954" (in Esperanto). Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ↑ "List of NGOs maintaining official relations with UNESCO". UNESCO. c. 2014. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Herzberg...la Esperanto-urbo" (in German). Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Programoj en Esperanto" (in Esperanto). Città del Vaticano: Radio Vaticana. Archived from the original on February 11, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ↑ Telepraph (September 22, 2006). "William Auld". Archived from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ Kuznecov, Aleksej (May 26, 2013). "Laste" (in Esperanto). Retrieved November 7, 2014.

Nia kantaro superis ciferon 3000!

- ↑ REJM (2009). "Filmoj en Esperanto" (in Esperanto). Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ "HORARIOS, BANDAS Y FRECUENCIAS EN VARIOS IDIOMAS" (in Spanish). Havana: Radio Habana Cuba. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Esperanto-TV is launched". Australian Esperanto Association. c. 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ Brants, Thorsten (February 22, 2012). "Tutmonda helplingvo por ĉiuj homoj". Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ↑ "Download Firefox in your language". 1998–2015. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ "LibreOffice Fresh". Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Esperanta Klavaro". windowsphone.com.

- ↑ Eddy, Geoff. "Why Esperanto is not my favourite Artificial Language". Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ↑ Rye, Justin B. "learn not to speak Esperanto". Archived from the original on October 30, 2005. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ↑ "La Chefaj avantaghoj de Ido" [The main advantages of Ido] (in Esperanto). Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- ↑ Rye, Justin B. "learn not to speak Esperanto: Sexism". Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Riisma esperanto" (in Esperanto). July 5, 1994. Archived from the original on September 24, 2006.

- ↑ Wennergren, Bertilo (August 16, 2015). "Seksa signifo de vortoj kaj radikoj en Esperanto" (in Esperanto). Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ↑ jalinh (June 6, 2007). "Lidé jsou počítače a Java je Esperanto ;)" (in Czech). Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ↑ Newman, Lily Hay (August 4, 2014). "Google Is Building the Esperanto of Fonts". Slate. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

Other websites

change| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

| Travel guide from Wikivoyage | |

| Learning resources from Wikiversity | |

- Esperanto on Citizendium

- Lernu! A popular website to learn Esperanto.

- Mp3 files of Esperanto radio broadcasts

- Plena Manlibro de Esperanta Gramatiko

- Music videos in Esperanto from Mauritius and Madagascar Archived January 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Learn Not To Speak Esperanto Archived October 30, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, a piece criticizing Esperanto's problems; and Why not to learn Esperanto, Claude Piron's answer to it.